Windows Internals: Secure Calls - The Bridge Between The NT Kernel and Secure Kernel

Introduction

As I have talked about before, often times the “normal” kernel, which runs in Virtual Trust Level 0 (VTL 0), requires the services of the Secure Kernel in VTL 1. Though VTL 1 is both a higher security boundary and isolated from VTL 0 often times VTL 0 needs “help” from VTL 1, or VTL 0 needs to enlighten VTL 1 about something which happened in VTL 0. For various reasons - whether any “less-trusted” security boundary needs to enlighten any other “more-trusted” security boundary about something which has occured, or because the less-trusted boundary does not have access to resources that the more-trusted boundary does - there is still some sort of interaction (although many times limited) between security boundaries. VTL 0 <-> VTL 1 is no different.

Communication between VTLs is certainly, in my opinion, an interesting thing. Because of this I decided to write this blog post about the secure call interface, which allows VTL 0 to request the services of VTL 1, or to allow VTL 0 to enlighten VTL 1 with various information. Additionally I am releasing a tool on the same subject called SkBridge, which is capable of issuing secure calls with user-specified parameters.

The reason this piqued my interest is for a few reasons. Firstly, secure calls are often made inline of various kernel operations, and are not made to be directly-callable. Because of this the arguments of secure calls are often fairly low-level and require reverse engineering to understand what kind of data is being passed to VTL 1 (and also what is received back from VTL 1 in VTL 0). This provoked me to try to create a harness (SkBridge) which could attempt to generically allow one to issue secure calls. Second, I like hypervisors a lot and I thought it would be interesting, since VTL 0 and VTL 1 are in isolated regions of physical memory, to see how the hypervisor “brokers” secure calls (and secure returns, which are transitions from VTL 1 to VTL 0 after a secure call). Since Hyper-V ships with no symbols, I thought this could be interesting to try and reverse engineer some of this functionality.

Another motivating factor for this tool and post were two older posts by my dear friend and someone who always helps me, Alex Ionescu, about writing a bridge to fuzz hypercalls. I thought it might be interesting to achieve this at a “bit of a higher level” with secure calls specifically (which uses hypercalls under the hood).

This post will be taking a look at the architecture which allows NT, which is in a completely isolated region of physical memory from the Secure Kernel, to “hand off” execution to the Secure Kernel, as well as showcase some of the common patterns NT and SK use in regards to copying and encapsulating parameters and output from VTL 0 <-> VTL 1 and VTL 1 <-> VTL 0.

Secure Call Interface

As a primer, there are a few different mechanisms which exist for communication between the Secure Kernel and NT. Namely they are:

- Secure calls

- Normal calls

- Secure system calls (does not result, technically speaking, in VTL 1 talking to VTL 0)

Normal calls allow the Secure Kernel to request the services of NT. The Secure Kernel is a small binary which only implements functionality it needs in order to avoid exposing a large attack surface. Notably, as an example, file I/O is not present in the Secure Kernel and requests to write to a file (like a crash dump for an IUM “trustlet” that is configured to allow a crash dump to occur, also known as a “secure process”) are actually delegated to NT.

Secure system calls provide services specifically to secure process running in VTL 1 (again, like a trustlet) and do not result in a “transition” between SK and NT (because the target system call is not in VTL 0, but in VTL 1).

This blog post will instead focus on the secure call interface, which often is erroneously called the “secure system call” interface (even by myself! The terms are confusing!).

The secure call interface allows the NT kernel, in VTL 0, to request the services of the Secure Kernel in VTL 1. Many of us will “jump” to the comparison of the secure call interface to that of the typical system call interface - and rightly so. In a secure call operation the NT kernel (in VTL 0) will package up some parameters that make up the secure call request and those parameters will be delivered to the Secure Kernel, who takes those parameters, fulfills the request, and returns a status (and potentially some output) to the NT kernel - very similarily to a typical system call.

However, there are only two components at play for the traditional system call interface - user-mode and kernel-mode (in which which a transition of the CPU occurs into kernel-mode, with a few nuances like switching to the thread’s kernel stack, etc.). It is important to note, however, that there is not such a “direct pipe” which allows the processor to start executing “in context of the Secure Kernel”, similar to when execution begins in kernel-mode for a particular system call.

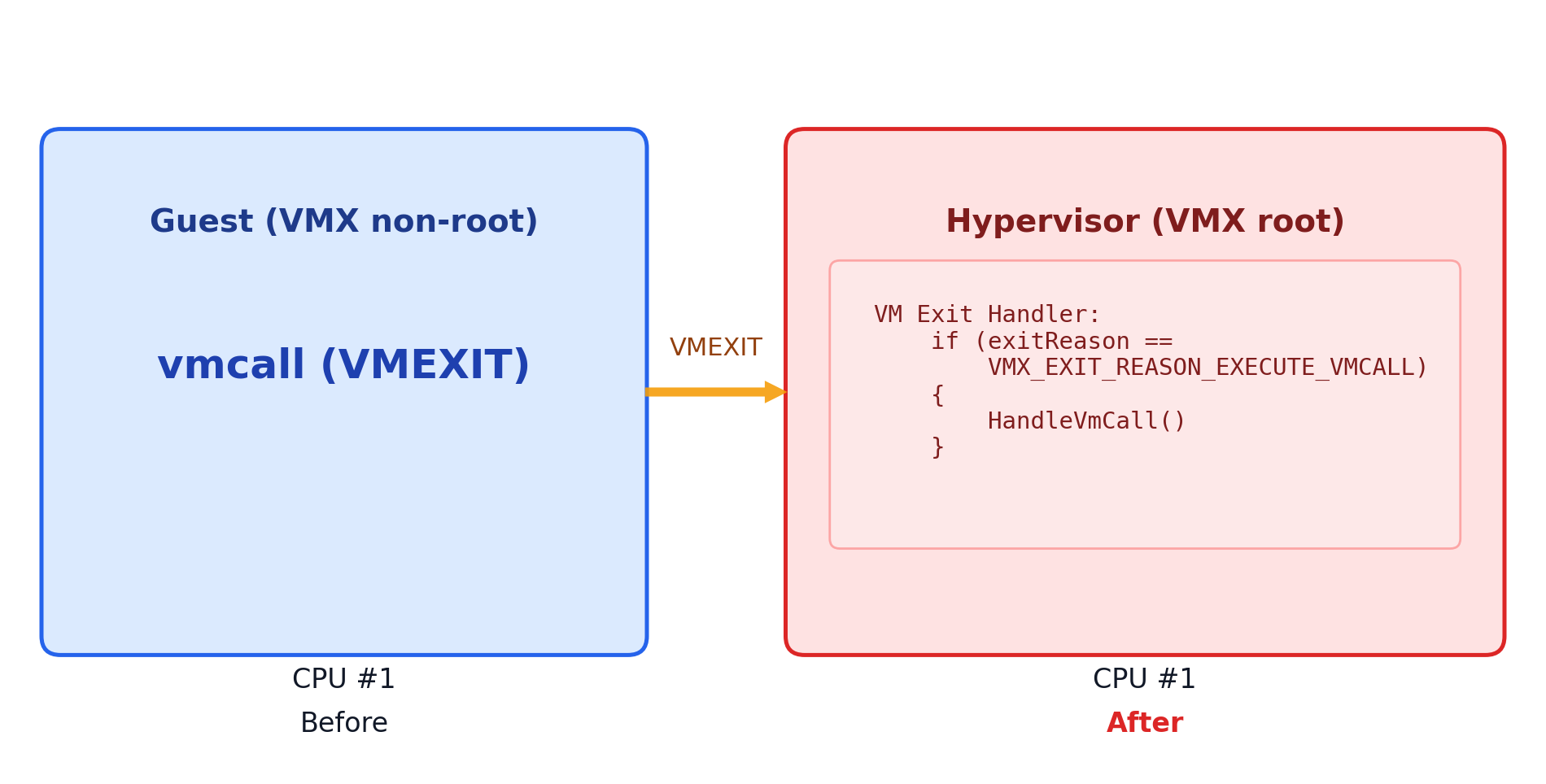

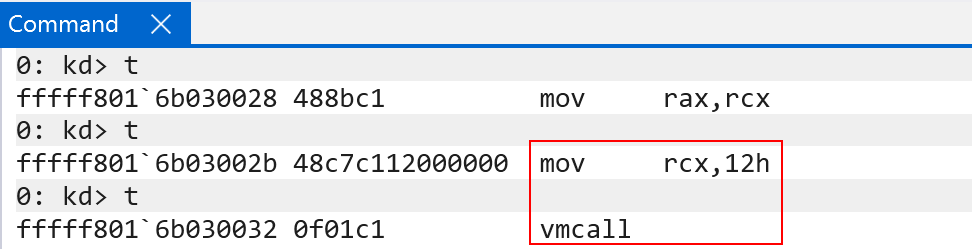

The secure call interface is really a “wrapper” for a specifc hypercall. A hypercall is a special operation (represented by the vmcall instruction) which transitions a processor which was previously executing in context of a guest (e.g., the processor was running code in context of a virtual machine, also known as guest) to what is known as Virtual Machine Monitor, or VMM mode (meaning execution on the processor is now executing in context of the hypervisor). This means that a hypercall is responsible for transitioning execution to the hypervisor (meaning for a secure call there are three components: the NT kernel, hypervisor, and Secure Kernel).

One common misconception is that the Secure Kernel “runs in the hypervisor”. This is actually not true. The Secure Kernel runs in an isolated physical address space (VTL 1), just like any other VM. When a secure call occurs, it is not NT being “directly piped” to SK. It is the hypervisor which then brokers the execution to the Secure Kernel when the “secure call hypercall” is received.

As I just mentioned, when a secure call happens a hypercall occurs. A hypercall is really just a very-specific way to cause a VM Exit. A VM exit is an “event” which occurs when the target processor goes from executing in context of a guest to executing in context of the hypervisor. Hypervisors typically register what is known as a “VM exit handler” in order to understand why the VM exit occurred and also how to handle the reason for the VM exit.

This means that when the secure call occurs it is Hyper-V’s VM exit handler which first starts executing (not the Secure Kernel) because a hypercall causes a VM exit. It is then up to Hyper-V to transition execution eventually to the Secure Kernel.

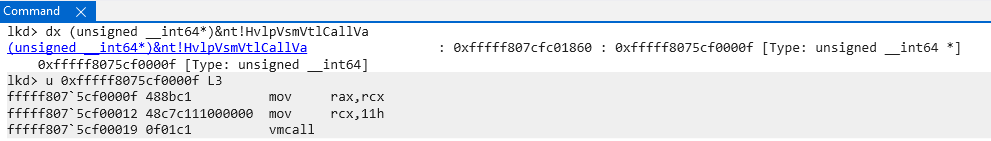

So what is the “difference between a secure call and hypercall”? The Microsoft Hypervisor Top Level Functional Specification, (also known as the TLFS), contains a list of all of the supported hypercalls. The answer to our question is that the “secure call” interface is effectively just a wrapper for the HvCallVtlCall hypercall! In other words, when a secure call occurs a specific hypercall is issued - causing a VM exit into Hyper-V. In NT, a pointer to the stub dedicated to this hypercall can be found at nt!HvlpVsmVtlCallVa.

The “secure call hypercall code” is that of 0x11, or 17 in decimal. This effectively means a secure call is “just” a hypercall which specifies this code. This specific hypercall code is a hint to Hyper-V which indicates that VTL 0 would like to request the services of VTL 1.

It is important to note that a vmcall instruction is spec’d to only run if the processor (which is currently running in “guest” mode) is at current privilege level (CPL) 0, or kernel-mode. vmcall is undefined in user-mode.

Once Hyper-V has execution it is then responsible for transitioning execution to the Secure Kernel (this is how execution goes from VTL 0 to VTL 1!). Hyper-V is the bridge between NT and SK, SK does not live “in the hypervisor”! For our purposes, which is to understand how the secure call “interface” works, we know that the first thing which happens as part of a secure call is that a VM exit occurs. This means that to better understand the secure call interface we first should attempt to locate Hyper-V’s VM exit handler!

Locating the Hyper-V VM Exit Handler

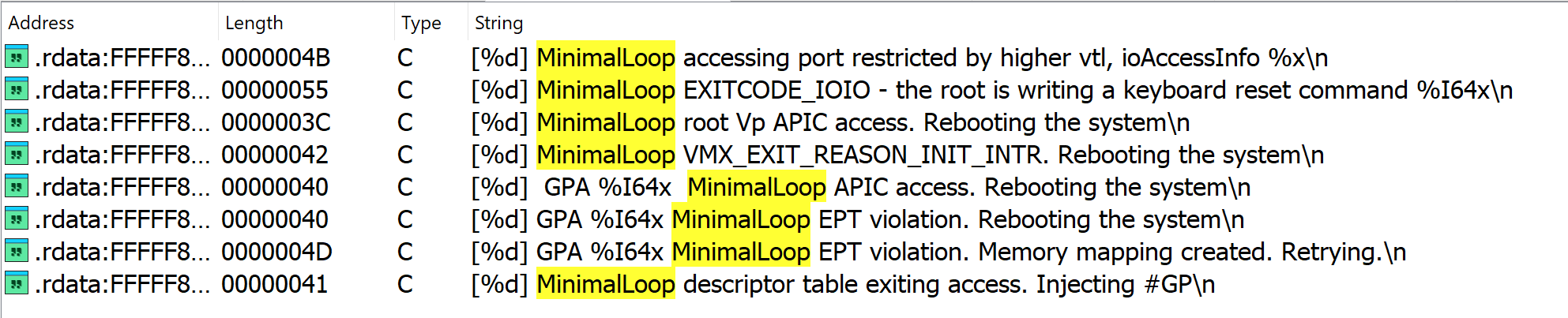

There is existing art on locating the VM exit handler for Hyper-V (for both AMD and Intel builds of Hyper-V). The canonical example is searching for a vmresume instruction (on Intel). A vmresume is responsible for transitioning the processor back to executing in context of a particular guest/VM (literally “resume” a VM). After a VM exit is handled, execution then eventually needs to go back to the guest. Typically a VM exit handler will, after handling the VM exit, issue the vmresume. Because of this the VM exit handler would then be in-and-around where a vmresume occurs. However, I am familiar enough with Hyper-V to know that there are certain debugging print statements located in the VM exit handler with the string MinimalLoop present. Searching for this string in IDA yields these print statements.

As we can see, a few strings like “EPT violation” (which can be a reason for a VM exit) and “VMX_EXIT_REASON_INIT_INTR” indicate logging is occuring in the VM exit handler. If we examine where this logging occurs, and if we then convert all integer-style values to appropriate VM exit reasons, we can see the VM exit handler is responsible for determining how to service the VM exit event.

It should be noted, additionally, that the VM exit reason is stored in the VMCS structure for the “current” guest (which caused the VM exit). The VMCS, or Virtual Machine Control Structure, is a per-processor structure. A VMCS represents the state of the “guest” running on a particular processor. Remember, with virtualization a processor can either be running in context of a particular guest (VM) or in context of the hypervisor software. We will see, later on, that both VTL 0 and VTL 1 have a VMCS which represents each of these “VMs”. What this means is that there is one VMCS loaded at a time on a processor (the VMCS is “per-processor”) but the data in the VMCS is per-guest. This is because there is a special CPU instruction, vmptrld, which allows the CPU to load a target VMCS pointer for a particular guest (thus allowing “multiple guests”). One VMCS “per-processor”, but we can swap out which VMCS that is based on the guest we want run on that processor.

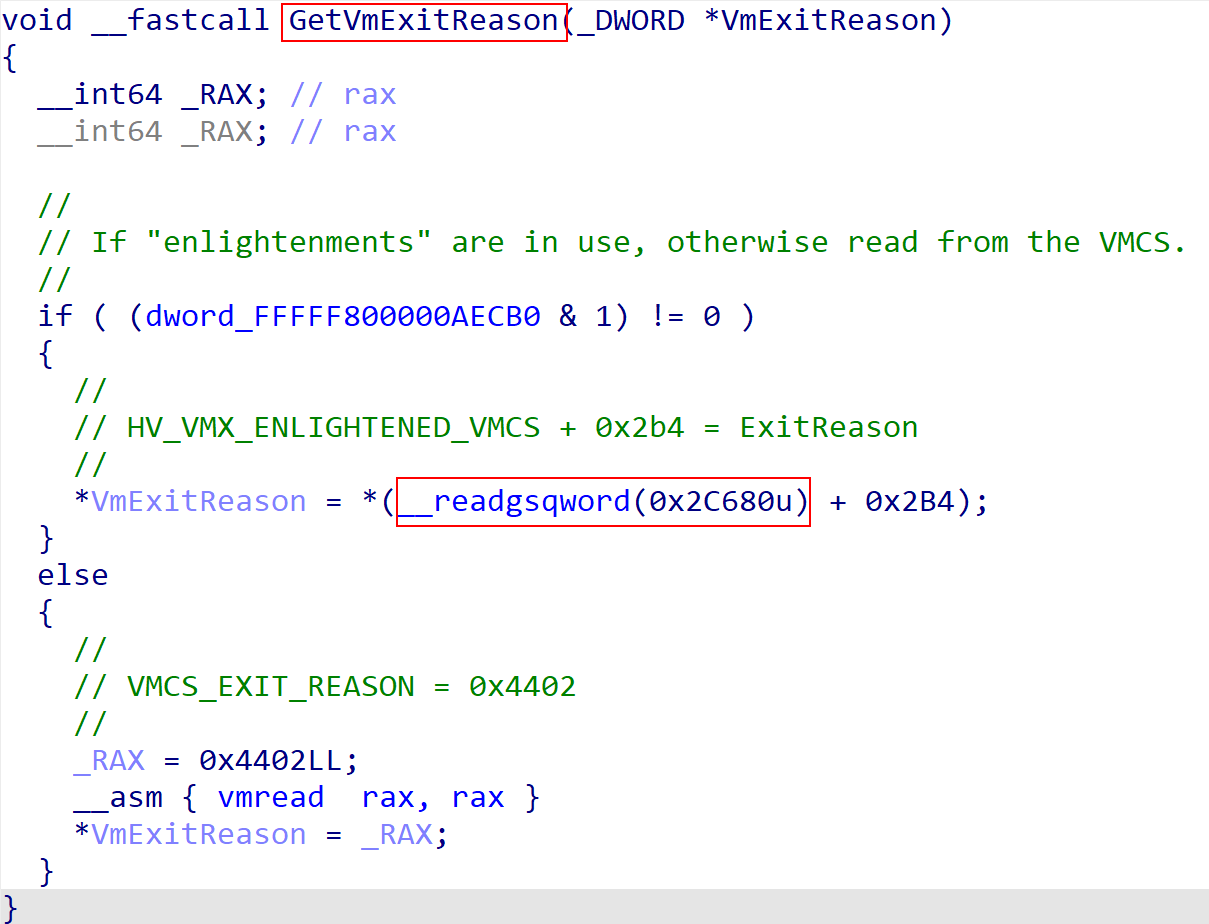

The VM exit reason can be extracted by the hypervisor simply by invoking the vmread instruction with a particular VMCS encoding value. However, the VMCS resides in physical memory. Because it would be more performant to just write to virtual memory Hyper-V has the concept of “enlightenments” where the VMCS is mapped into virtual memory and is simply written to/read from its virtual address. Additionally, because (as we mentioned) the VMCS is per-processor Hyper-V also tracks the “current” VMCS through the gs segment register. Saar Amar talks about this in this Hyper-V research blog. In addition to the “current” VMCS there are many other important structures, like the “current” virtual processor, which are also tracked through the gs segment register on a particular processor. These offsets from the base of the gs segment register (which we will demonstrate how to find in this blog post) often change, and the data may not look the same from version-to-version.

As we can see, gs:[2C680h], on this particular build of Windows (24H2), contains the virtual address of the “current” VMCS. We know this because we can see here either the physical address of the VMCS is used, or the “enlightened” version. Because of this, we can deduce that since the VMCS is tracked via the current CPU’s gs segment register it is also very likely also that the rest of the important structures related to the hypervisor’s capabilities (like the “current virtual processor”) are also tracked via the gs segment register.

Because the rest of our analysis will require knowledge of where these structures are, we need to find where they reside. A wonderful blog exists on this, from Quarkslab, talking about how to identify much of this data. Unfortunately much of the data has changed between the time that blog was written, and now. In fact, even some of the structures in-memory do not contain the same “layout” as that of the Quarkslab blog. Because of this, its worth examining how to first identify this information. We will do this by first continuing into our VM exit handler, by locating where hypercalls are handled.

Locating the Hypercall Handler

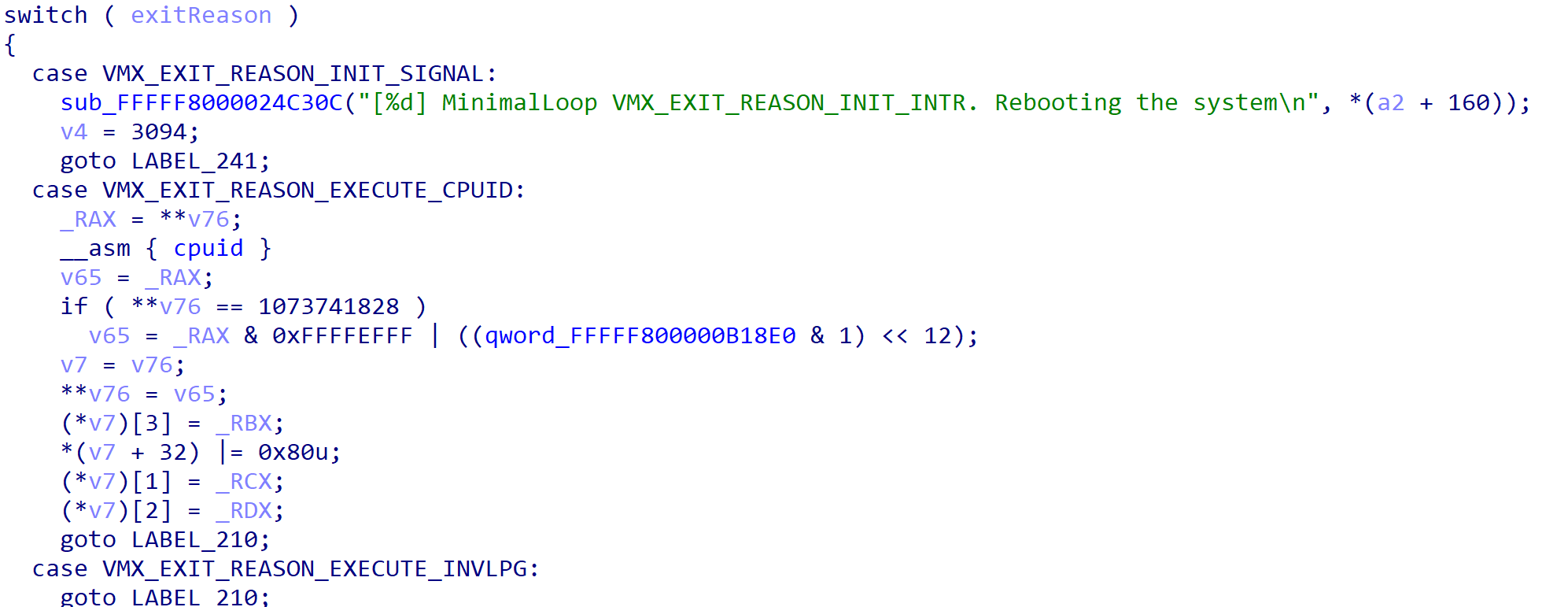

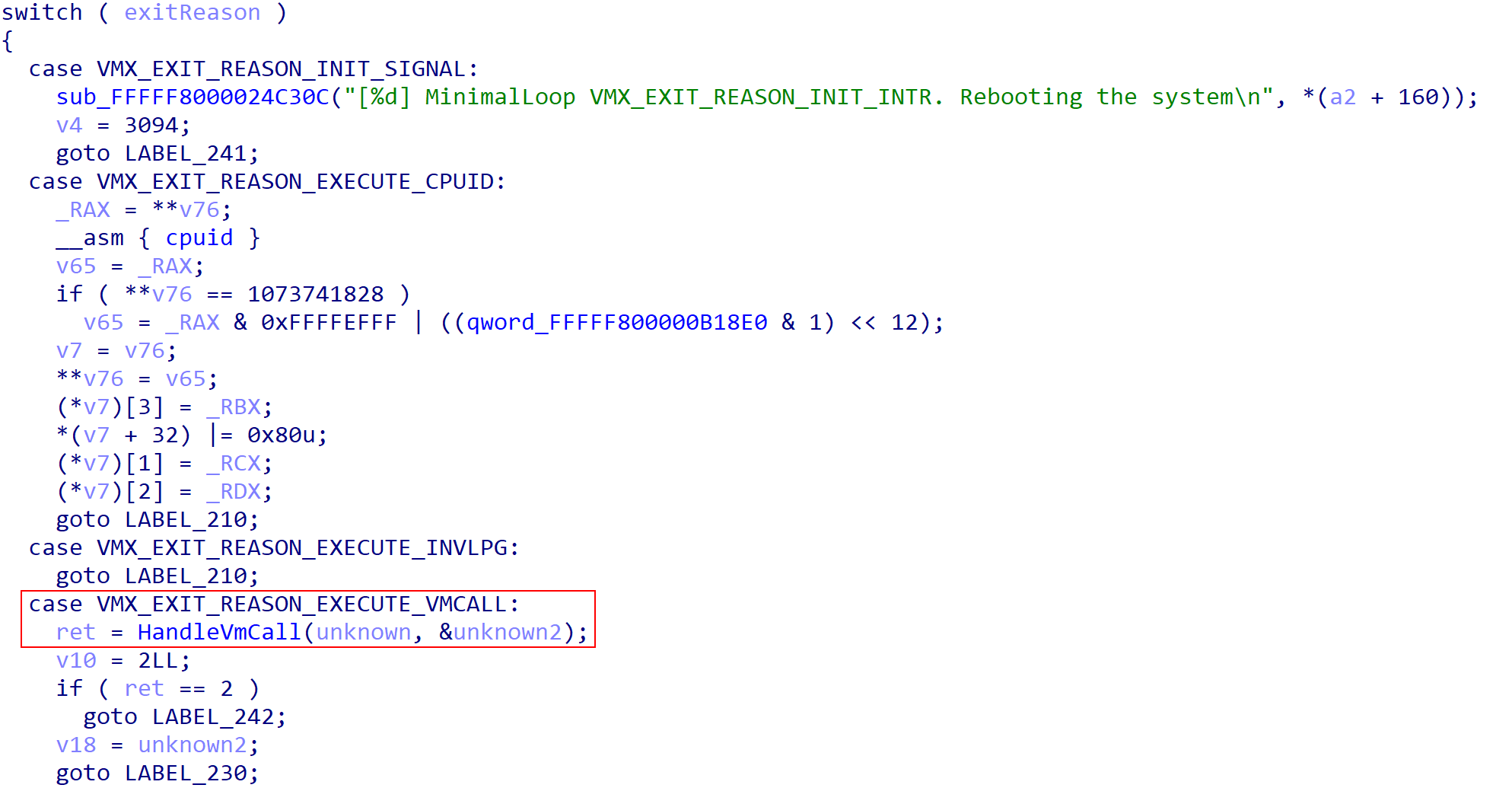

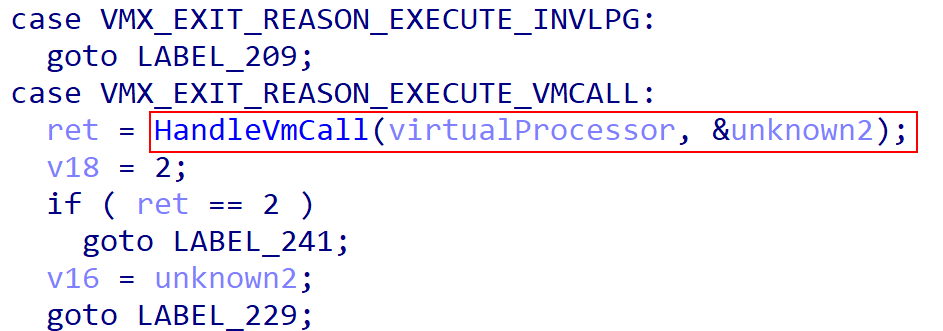

Now that we know where the VM exit handler resides, we now need to identify where the handler for the “hypercall” VM exit reason occurs. This is because secure calls will result in a hypercall. Coming back to the VM exit handler, we can see there is a switch/case statement for handling all of the various VM exit reasons. We can also see a handler for VMX_EXIT_REASON_EXECUTE_VMCALL, which is the exit reason for a hypercall. This is our hypercall handler!

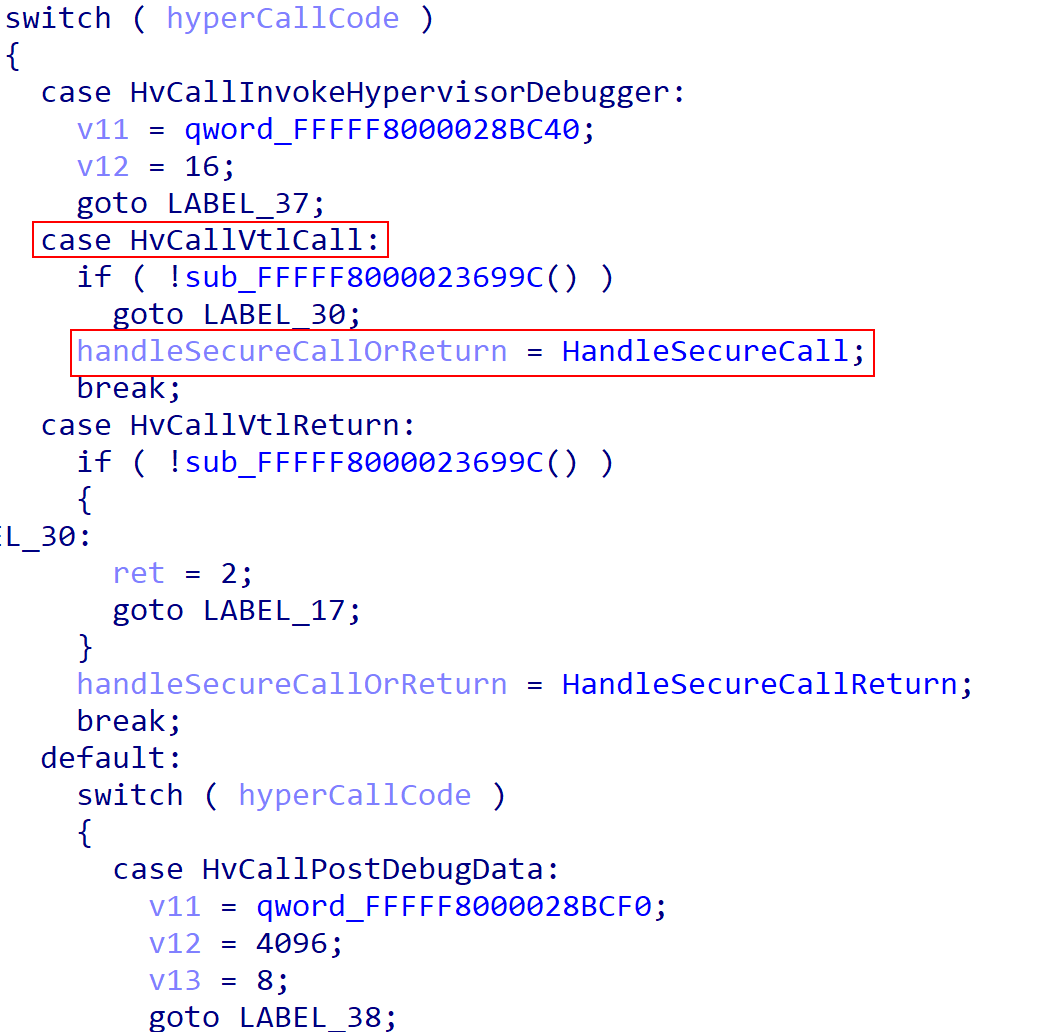

We still do not know what the arguments to what we now will call HandleVmCall will be, but we know that this is where hypercalls are handled. Taking a look at HandleVmCall we can once again see another switch/case going over many of the supported hypercall values. The hypercall values can be extracted either from the TLFS, or more-easily through Alex Ionescu’s HDK project.

We can see that there is a dedicated handler to the HvCallVtlCall hypercall type. HvCallVtlCall has a value of 0x11, or 17 in decimal. This is the secure call hypercall value and, thus, is our secure call handler!

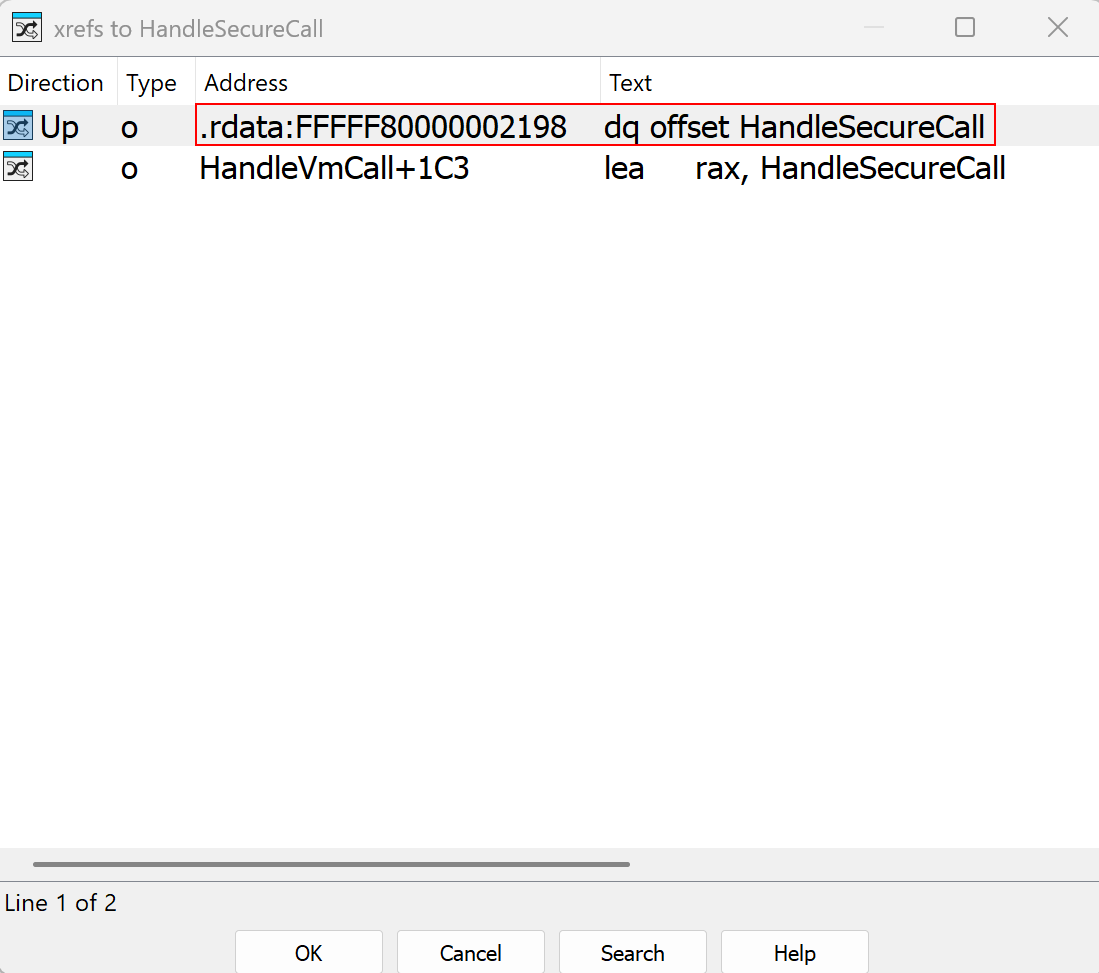

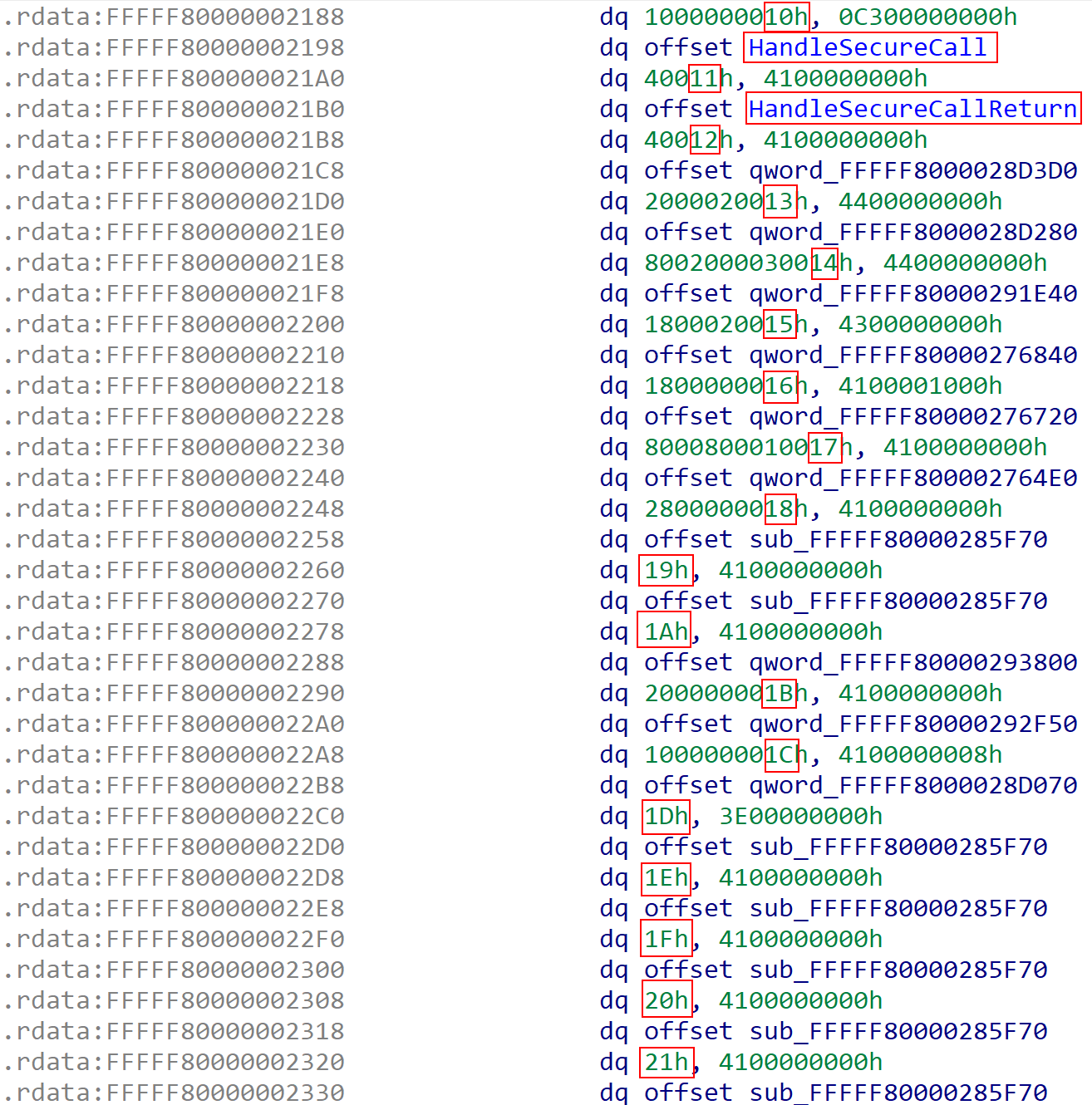

It’s also possible to get a full list of all the hypercall handlers. To do this one simply needs to locate the “hypercall table”, which is stored in the .rdata portion of Hyper-V (it was once in a .CONST section). This is important for us because we actually need to disassemble one of the hypercall handlers. Why is this? Remember - we still need to locate structures such as the current virtual processor and current partition, because they will provide much of the data to the secure calls that we need to inspect. Saar mentions in his blog that most hypercalls first check the current partition for the correct permissions/privileges in regards to the ability to execute a particular hypercall (a partition may not have the privileges to do so, and each guest resides in a child partition while VTL 0 and VTL 1 reside in the root partition).

Because some hypercalls require special privileges there is a “privileges mask” which exists in each partition. Therefore, if we can locate the handlers for the hypercalls we can then inspect where this privilege check occurs. If we can find this privilege check, and if we know the privilege mask resides in the “current partition structure” we then can locate where the current partition resides!

As we can see, the hypercall table has a layout where the hypercall’s number is mapped to a particular hypercall handler routine. This is either an actual function which sets up a proper stack frame/etc., or is an assembly routine which does some necessary manual tasks.

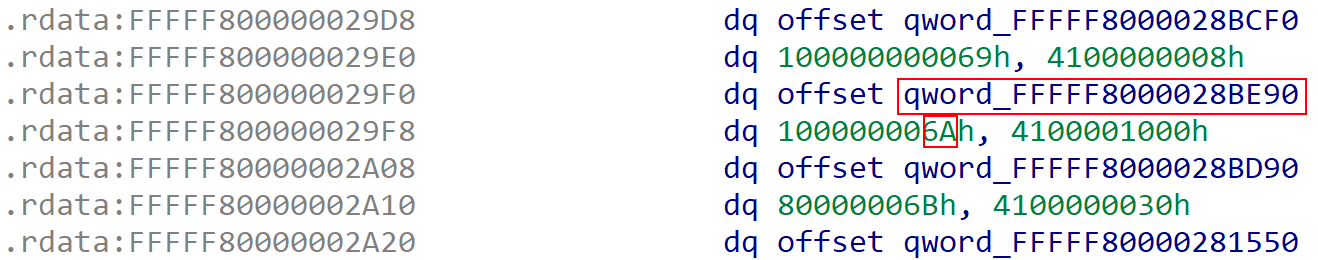

To locate the current partition, let’s take one of the hypercall routines - in this case HvRetrieveDebugData, which is hypercall number 0x006a according to the TLFS.

Here we can now use WinDbg to load Hyper-V as data and examine this assembly stub. Use the command: windbgx -z C:\Windows\system32\hvix64.exe (for Intel-based Hyper-V).

There is a constant, in this case, located at gs:[360h] which is some sort of structure that has a bitmask at offset 0x1b0. We know that all hypercalls (usually) have this exact check at the beginning of the routine in order to validate privileges. This indicates that gs:[360h] must be the “current partition” and that 0x2b is the privilege mask! Additionally, if we examine the HV_PARTITION_PRIVILEGE_MASK enumeration, we can see that 0x2b is the Debugging bit - all but verifying that this is the partition, as the hypercall we are investigating is a debugging-related hypercall.

We now know the locations of the current VMCS and of the current partition. However, because there are some details still missing (especially because we don’t know how the VM exit handler receives its arguments and, thus, we don’t know the arguments for the secure call handler). The next step of the equation is to locate one of the most crucial data structures in Hyper-V, the Virtual Processor (VP). This data structure provides most of the arguments to both the secure call handler and the VM exit handler.

Locating the Virtual Processor (VP)

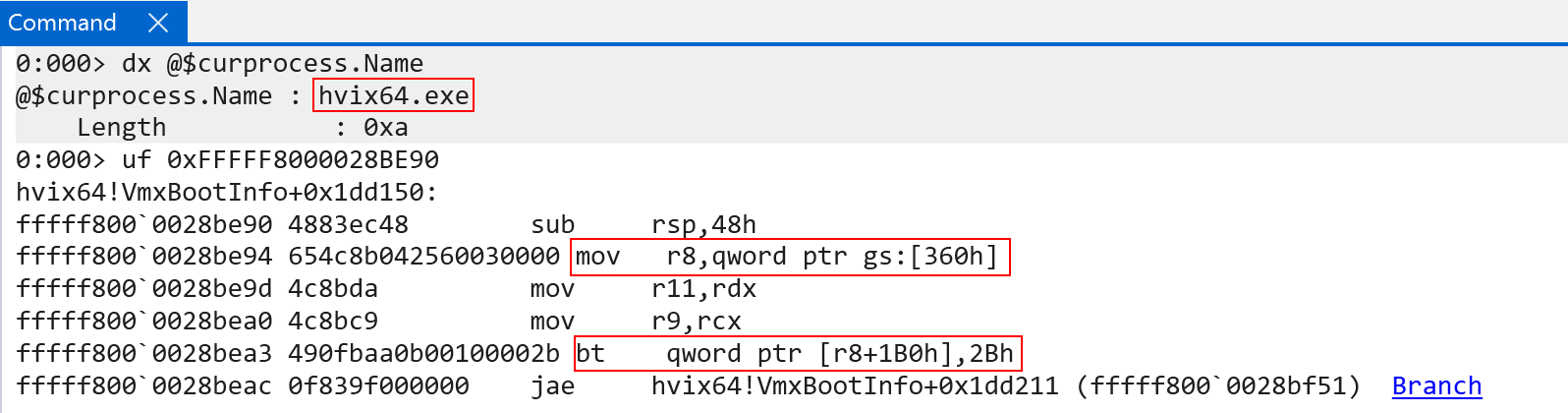

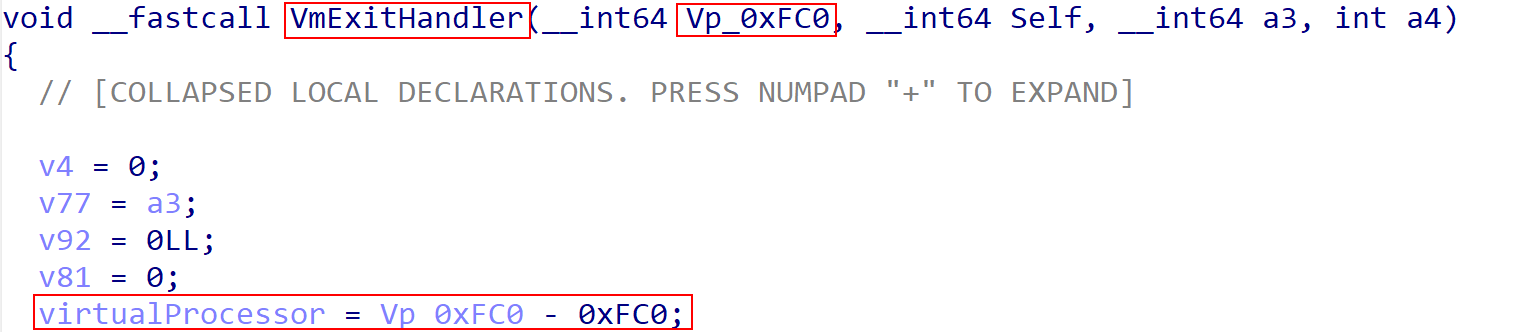

I found that locating the VP is fairly straightforward, but relies (in my opinion) on some trial-and-error and “assumptions”. The Quarkslab blog outlines how they were able to find the VP, but on my build of Hyper-V (which is now 4 years newer), some of the semantics and offsets have changed. In our case, to find the VP, we “go back” as far as we can (using cross-reference functionality in IDA) to see how the VM exit handler receives its arguments. The “main” argument given to the VM exit handler “originates” several calls up in the call chain. What I mean by this is that the VM exit handler receives arguments from a function which itself received the same arguments from another function (all the way “up”) which “passed them on” to the VM exit handler. Eventually we come to the following function in Hyper-V which will eventually pass them on to the VM exit handler.

Hyper-V does not ship with any public symbols. So although this looks abstract, sub_FFFFF800003321C8 is the function which will eventually invoke the VM exit handler. In this case, a few things can be noticed. Firstly we can see that from gs:[0h] a structure, referred to as “self” in this case, is preserved. “Self” in this case means that gs:[0h] simply references itself and is just a pointer “back to itself”. We can then see that what we will refer to as “the virtual processor” is extracted at offset 0x368 from the self-pointer. This is another way of expressing gs:[368h]. This is the current processor’s virtual processor structure! The VP structure has a specific structure member, located at offset 0xFC0, which is passed to the VM exit handler. The VM exit handler also will preserve the virtual processor as a local variable.

The virtual processor is then passed to the VM call handler which, in turn, will pass it on to the secure call handler (which is just a hypercall with a hypercall code of 0x11).

The Secure Call Handler

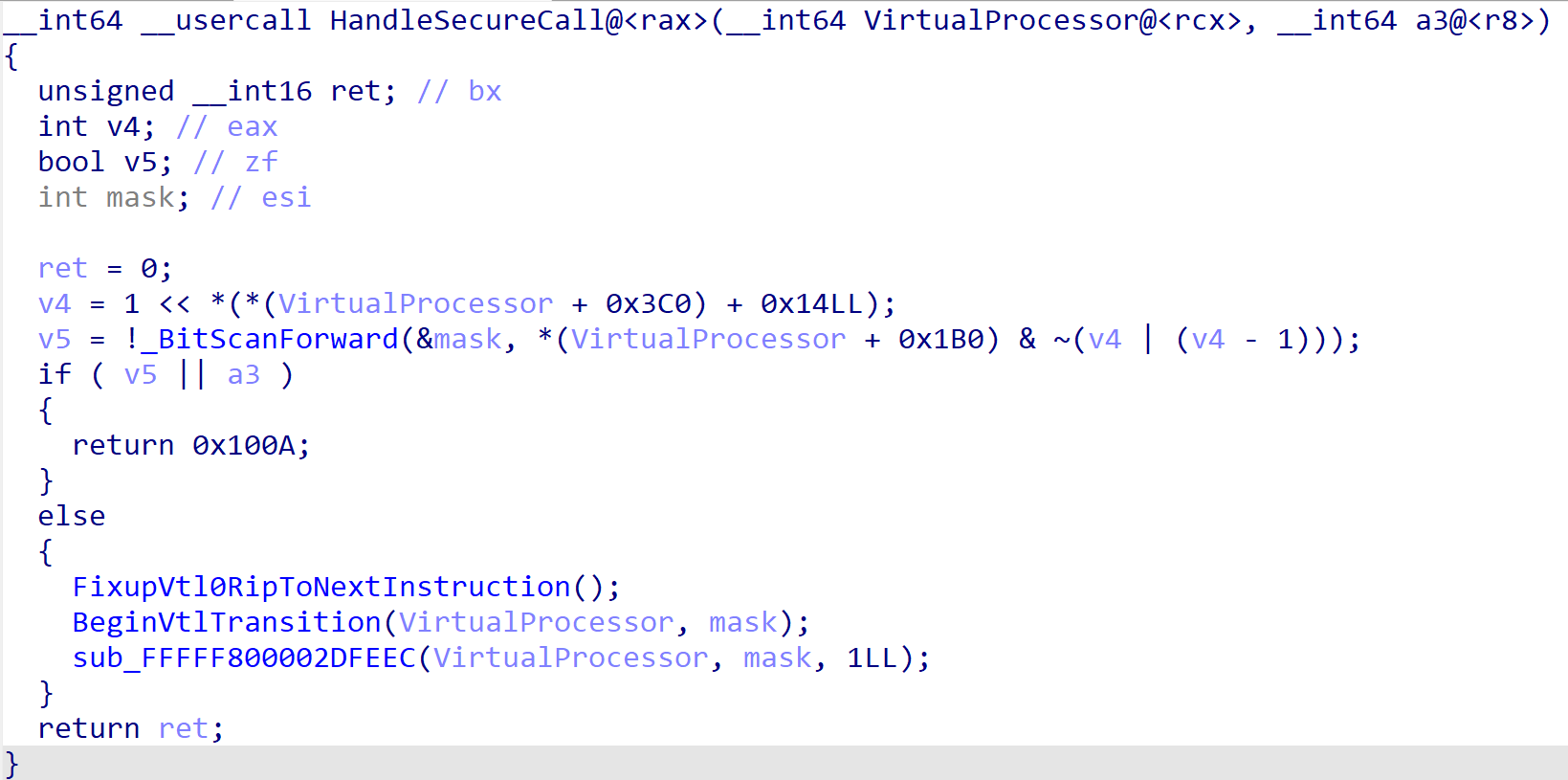

Now that we have our feet under us, we can turn our attention to the actual “secure call handler”, which is just a hypercall handler for hypercall code 0x11 (HvCallVtlCall).

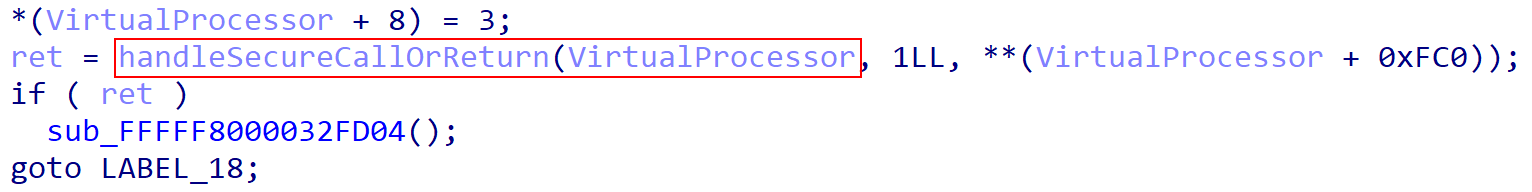

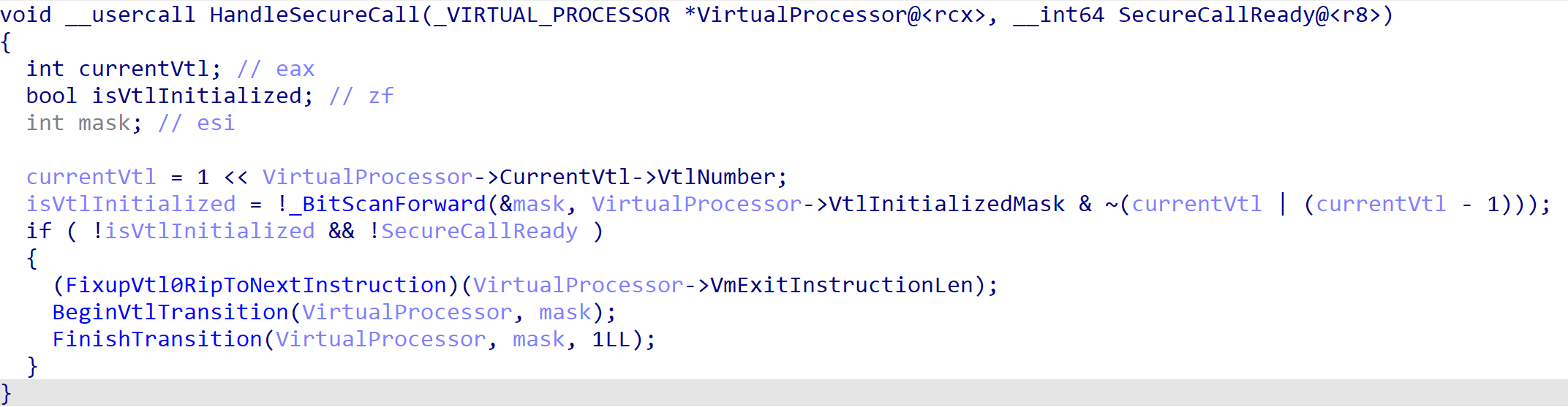

The secure call handler will, first, extract VirtualProcessor + 0x3c0, which seems to be a structure, and then will extract from what seems to be another structure at offset 0x14. One thing we must remember is that, when Virtual Secure Mode (VSM) is enabled, we have (currently) two Virtual Trust Levels (VTLs). We have VTL 0 (normal world) and we have VTL 1 (secure world). The thing to remember here is that a particular processor, when VSM is enabled, executes in context of a particular VTL as well! Hyper-V manages the “current VTL” information via the VP structure. In this version of Hyper-V, the “current VTL” is maintained through the current virtual processor at offset 0x3c0. Additionally, offset 0x14 into this “VTL structure” contains the VTL associated with the VTL structure (which, in this case, means the VTL of the current processor).

The curious reader may wonder where, what I am calling VtlInitializedMask, comes from. As part of the “song-and-dance” that Hyper-V and the Secure Kernel perform, to initialize the VTLs, a “mask” (managed by the VP) maintains “state” associated with the VTLs that are initialized. This also brings up, since it is seen in the screenshot below, the VP maintains both the current VTL information and an array of all known VTLs.

The first thing the secure call handler does, if we are eligble to issue the secure call (the target VTL is initialized), is we “fixup” the instruction pointer for the current VTL. There is one crucial detail to recall here - with the presence of VSM we have two VMCS structures which can be used - the VMCS associated with VTL 0 (which is the current VTL, since this is a secure call and VTL 0 and requesting services of VTL 1) and the VMCS associated with VTL 1. The “typical” specification for handling VM exit (like our secure call) is to then increment the instruction pointer of the guest which caused the VM exit to the next instruction to be executed when the VM enter occurs later (when the hypervisor is done and the guest starts executing again). This is the first thing that is done so that VTL 0 returns to the “next” instruction and does not re-issue the hypercall (in this case “secure call”). This is done be either leveraging the “enlightened” VMCS, or by reading from the VMCS directly using the vmread and them vmwrite instructions to update the guest’s instruction pointer.

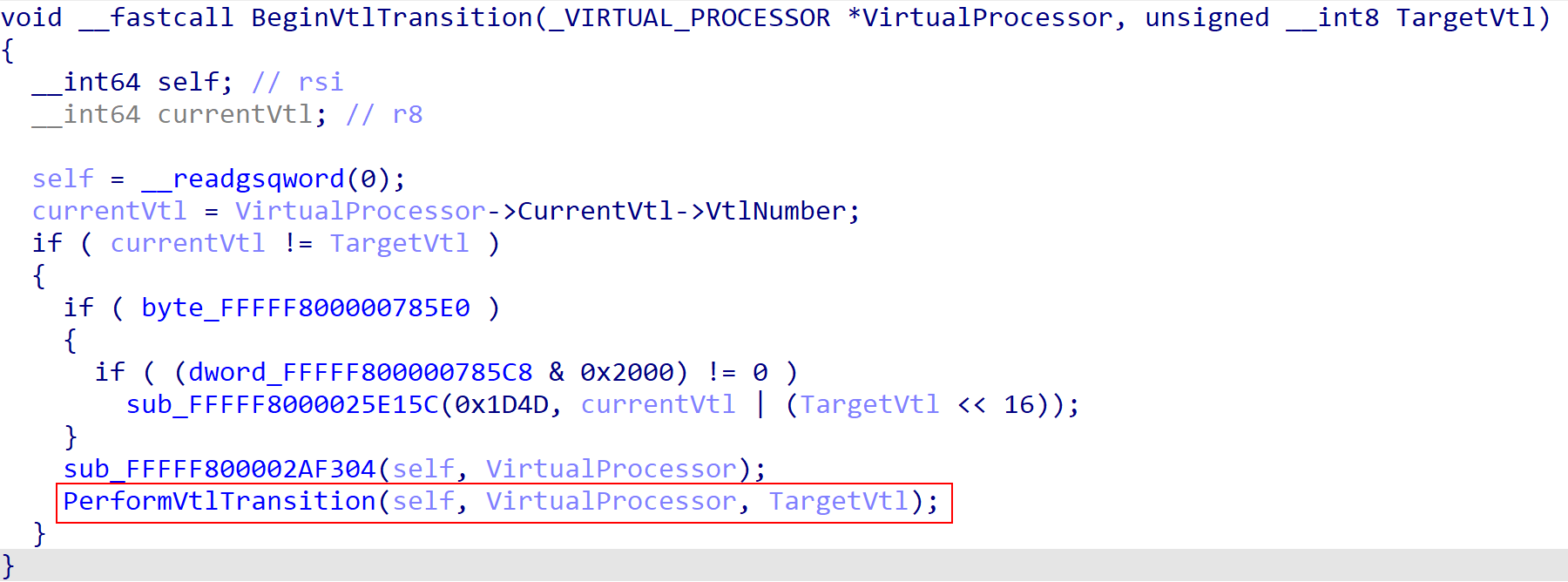

Once the instruction pointer for VTL 0 has been fixed up, the transition to the new VTL (VTL 1) begins. This is achieved through what I am calling the BeginVtlTransition function. For our purposes this function will ensure that the target VTL differs from the current VTL (as this is a VTL transition).

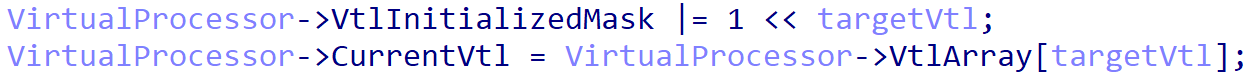

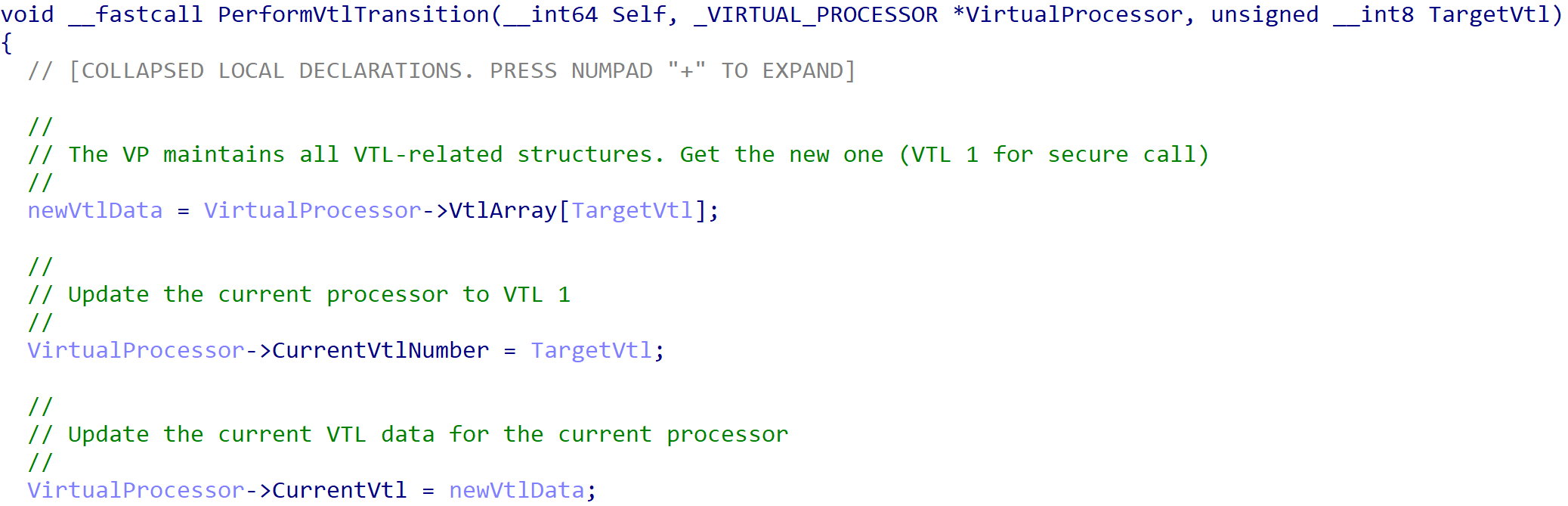

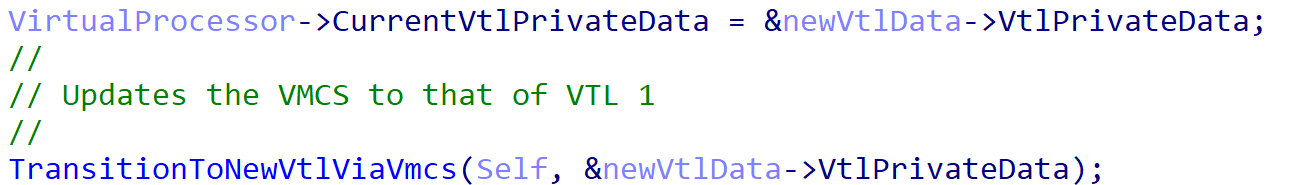

When the actual VTL transition occurs, the first thing that happens is the current VTL data for the current virtual processor is updated. In this case, the current VTL is now VTL 1.

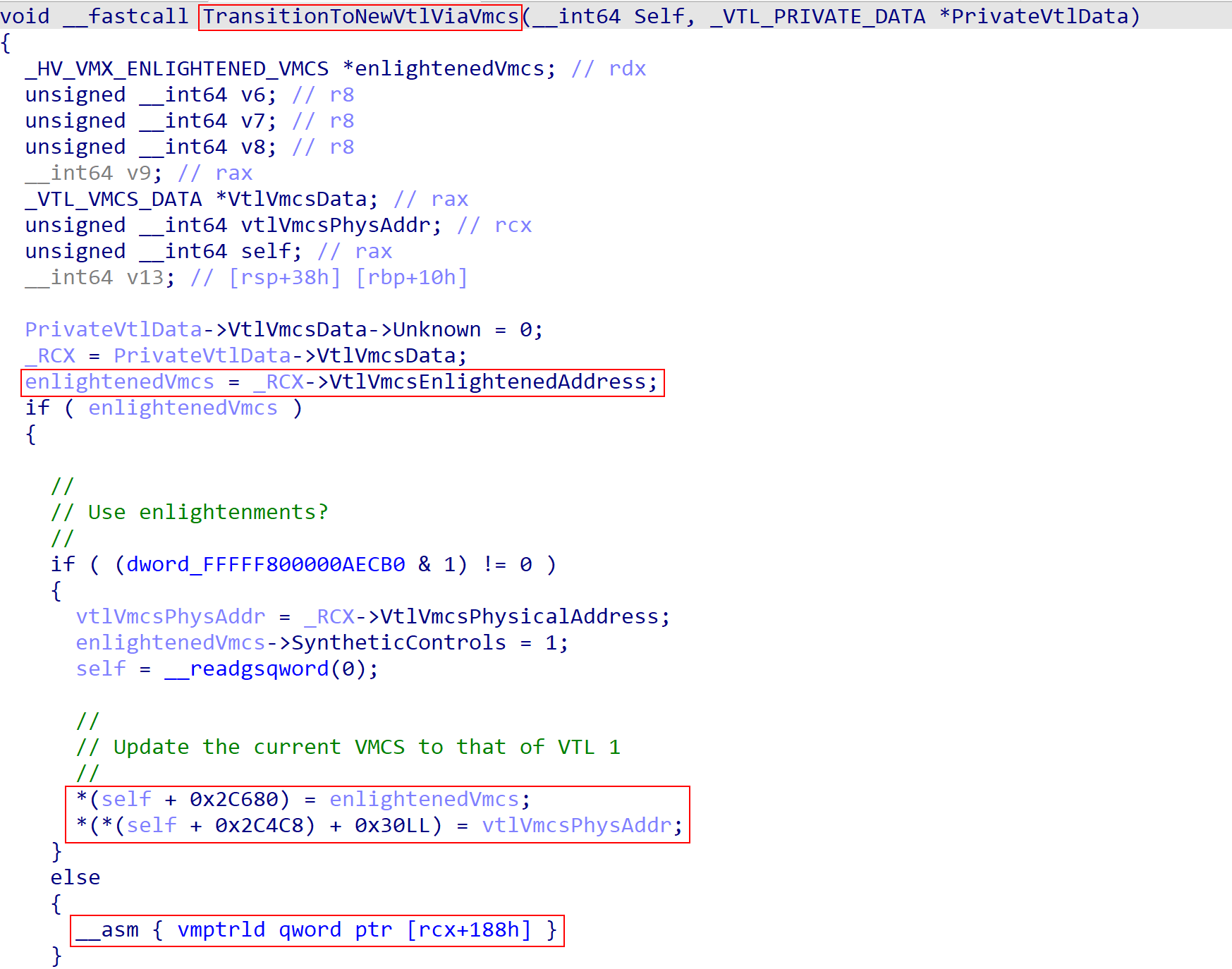

After the relevant information is updated the actual VMCS of the current VP needs to be updated to that of the new VTL (VTL 1). This is done through a function I have named TransitionToNewVtlViaVmcs. From the “new VTL data” comes what I am referring to as private VTL data. This could also be renamed to “VTL state data”. The “state data” or “private data” is necessary as it contains the target VTL’s VMCS pointer.

With the target VTL’s information now in-scope, the transition to the new VTL can occur by updating the current VMCS to that of, in our case, VTL 1. The vmptrld instruction will be used to achieve this if enlightenments are not available. Otherwise the virtual address of the VMCS is used.

The “guest RIP”, “guest RSP”, etc. are now all that of VTL 1 and execution is still in the hypervisor. The new “guest RIP” and “guest RSP” (which are that of VTL 1) will be used when the “VM resume” occurs to allow the processor to start executing in context of the new guest (which is now VTL 1 after the VTL transition). The new guest RIP and guest RSP come from the last time VTL 1 caused a VM exit. So whatever VTL 1 was doing at the time it performed the last action that caused a VM exit is the state of the processor when the VM resume will occur. From here Hyper-V can simply issue a vmresume instruction and the new “guest” that will start executing is VTL 1! This is how VTL 0 asks Hyper-V (via the hypercall) to have VTL 1 start executing.

This means we now have a primitive (secure call) to transition into VTL 1, requested by VTL 0 and serviced by the hypervisor as we have seen, but the crucial question here is what will be executed in VTL 1 when the VM resume occurs? The Secure Kernel is setup in such a way, when handling secure calls, to cleverly leverage code routines and hand-crafted assembly code that exist very close together in memory so that when the hypervisor issues the VM resume and execution occurs in VTL 1, the correct handlers are present in the Secure Kernel to service the secure call.

VTL 1 State Preservation And VM Exit Back To Hyper-V

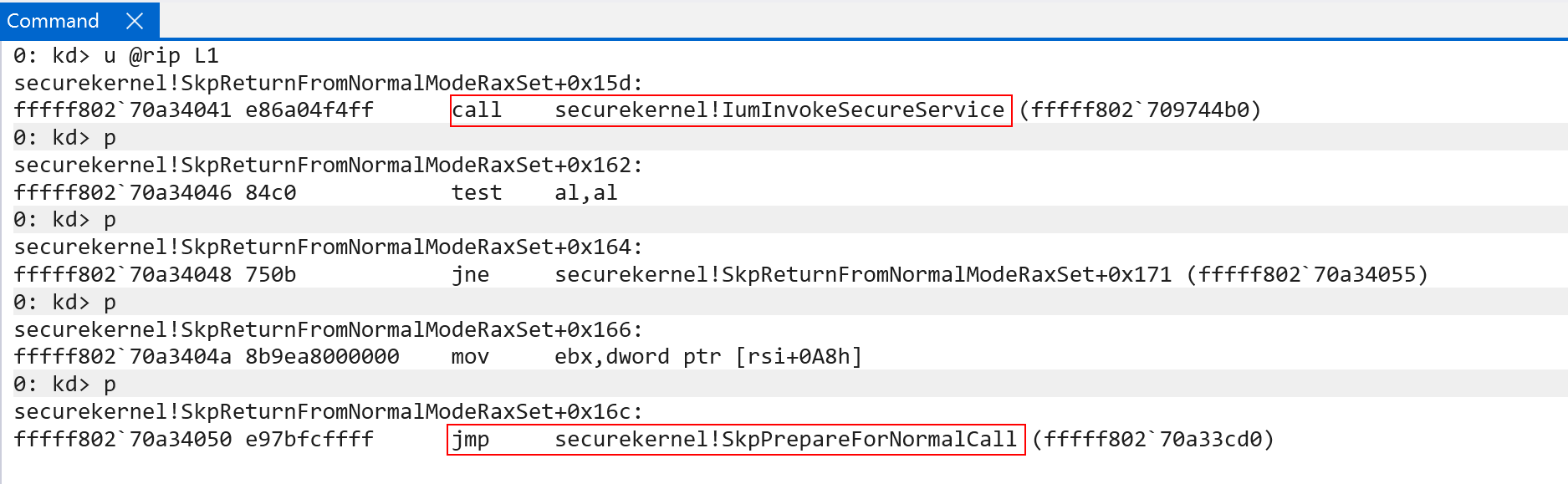

Let’s now turn our attention to the Secure Kernel’s “famous” function, securekernel!IumInvokeSecureService. Using SourcePoint’s debugger, which I have previously outlined using, we can debug the Secure Kernel to gain insight into how VTL 1 preserves it state in such a way that when a secure call occurs execution seamlessly results in the secure call being serviced by securekernel!IumInvokeSecureService. To understand this let’s start at what the Secure Kernel will do after servicing a secure call, in order to gain insight into how VTL 1 properly preserves it state before performing the VM exit back to Hyper-V.

When the secure call has been serviced (via securekernel!IumInvokeSecureService), an indirect jump occurs to securekernel!SkpPrepareForNormalCall. It is crucial here that this is a jump, not a call, as no return address is pushed onto the stack. This is because the thread currently executing may not end up being the thread which actually processes the return back into Hyper-V.

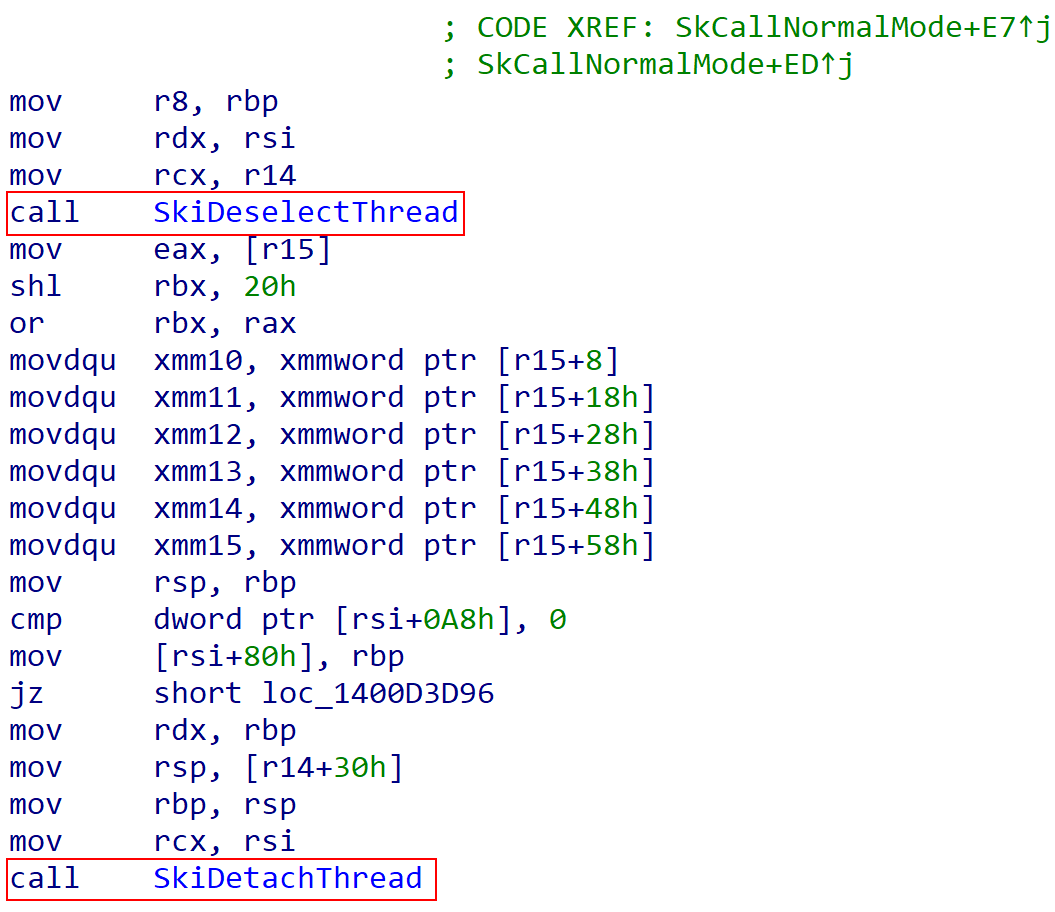

Secure calls are handled, usually, in context of a particular thread (more on the actual interface towards the end of this blog post). Because of this two functions are called, securekernel!SKiDeselectThread and (potentially, if a specific thread is necessary - we will talk about this later) securekernel!SkiDetachThread. This allows us to “stop executing” in context of the particular thread in which the secure call was handled.

We are now “back” to the thread which originally started executing when VTL 1 was “entered” into via the secure call (more specifically this is the thread which was represented by the “guest RSP” and “guest RIP” update we talked about earlier when the VMCS for VTL 1 was loaded and the VM resume occured to dispatch VTL 1).

With the correct thread selected it is time to preserve the current state of VTL 1 before the VM exit. Recall that all of the code/assembly which is responsible for preserving the current state of execution is tightly-packed right next to each other in memory. This allows execution to occur linearly and not require complex jumps/calls across several pages of memory and to allow the stack to be setup in a very particular manner. securekernel!SkpPrepareForNormalCall then invokes securekernel!SkpPrepareForReturnToNormalMode (which are right next to each other in memory). This function is then where “the magic happens”.

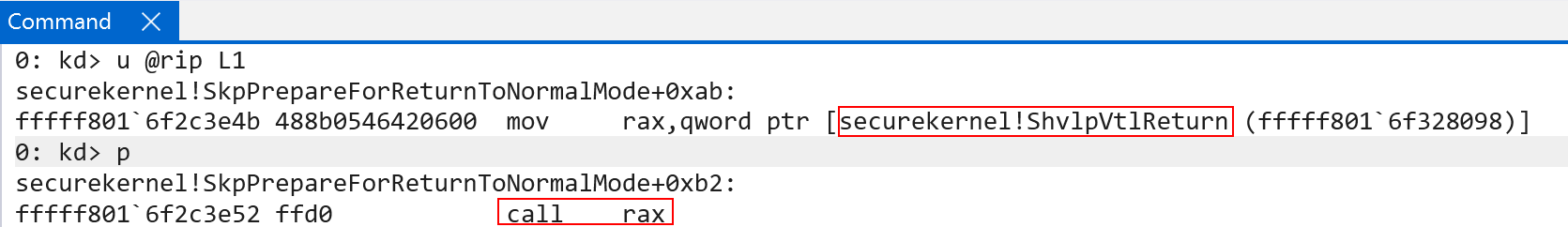

Eventually an indirect call to securekernel!ShvlpVtlReturn occurs. This time we issue a call instead of a jump. This is crucial because a call, as you may know, will push the address of the next instruction onto the stack.

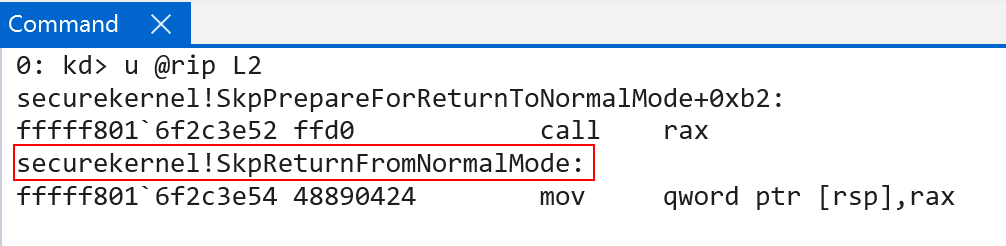

In this case the address of the next instruction is securekernel!SkpReturnFromNormalMode! This means that when the VM exit from VTL 1 occurs back into Hyper-V (which is known as a “secure call return”) it will be this address which is pointed to by the top of the guest’s stack (guest RSP). Why does this matter? The current function about-to-be executed (securekernel!ShvlpVtlReturn) simply issues a vmcall (hypercall) with the secure call return hypercall code (0x12). When this happens, the VM exit happens back into Hyper-V - and the address on the stack is that of securekernel!SkpReturnFromNormalMode.

Hyper-V, on receiving the secure call return hypercall, will also perform a similar fixup to that which we saw earlier - specifically Hyper-V will fixup the guest’s RIP (the guest RIP from the VMCS of VTL 1). The “current” guest RIP for VTL 1 points to the vmcall (the secure return). Hyper-V will increment VTL 1’s RIP to the next instruction after the vmcall. This is important because the instruction after the vmcall is simply a ret (return)! What this allows the Secure Kernel to do is that, upon the next VM entry into VTL 1, this ret will execute and, thus return into whatever is stored on the guest’s stack pointer. In this case, as we can recall, VTL 1 strategically configured it’s stack pointer to be securekernel!SkpReturnFromNormalMode! securekernel!SkpReturnFromNormalMode is the Secure Kernel function responsible for dispatching the appropriate logic as to why the VM entry into VTL 1 occured (hypercall, intercept, etc.)! This “packing together” of functions near the vmcall instruction allows the Secure Kernel to “always be ready” to handle any VM entry, by allowing VTL 1 to simply let securekernel!SkpReturnFromNormalMode to handle any entry into VTL 1 from VTL 0 (normal mode)!

Now that we have examined the underlying mechanism which allows for VTL 0 -> Hyper-V -> VTL 1 “secure calls” and returns from VTL 1 -> Hyper-V -> VTL 0, let’s actually examine, from the “NT” side the actual “secure call interface” and the nuances surrounding it.

Secure Call “Interface”

The secure call interface, as I have mentioned in previous blogs (and this one), all revolves around the NT function nt!VslpEnterIumSecureMode, which I have prototyped as such:

NTSTATUS

VslpEnterIumSecureMode (

_In_ UINT8 OperationType,

_In_ ULONG64 SecureCallCode,

_In_ ULONG64 OptionalSecureThreadCookie,

_Inout_ SECURE_CALL_ARGS *SecureCallArgs

);

The SECURE_CALL_ARGS structure is undocumented, but is known to be 0x68 (108 bytes) in size from Windows Internals 7th Edition, Part 2. To the best of my ability I have reverse engineered this structure to the following layout:

union SECURE_CALL_RESERVED_FIELD

{

ULONGLONG ReservedFullField;

union

{

struct

{

UINT8 OperationType;

UINT16 SecureCallOrSystemCallCode;

ULONG SecureThreadCookie;

} FieldData;

} u;

};

typedef struct _SECURE_CALL_ARGS

{

SECURE_CALL_RESERVED_FIELD Reserved;

ULONGLONG Field1;

ULONGLONG Field2;

ULONGLONG Field3;

ULONGLONG Field4;

ULONGLONG Field5;

ULONGLONG Field6;

ULONGLONG Field7;

ULONGLONG Field8;

ULONGLONG Field9;

ULONGLONG Field10;

ULONGLONG Field11;

ULONGLONG Field12;

} SECURE_CALL_ARGS, *PSECURE_CALL_ARGS;

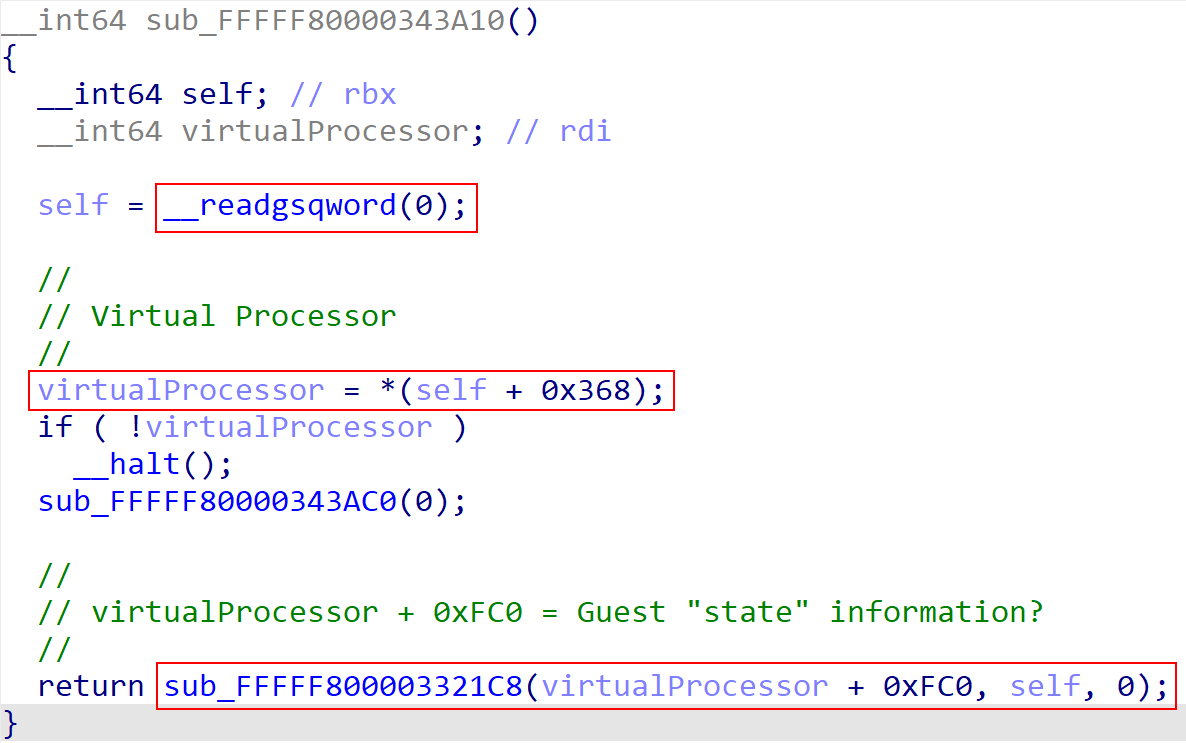

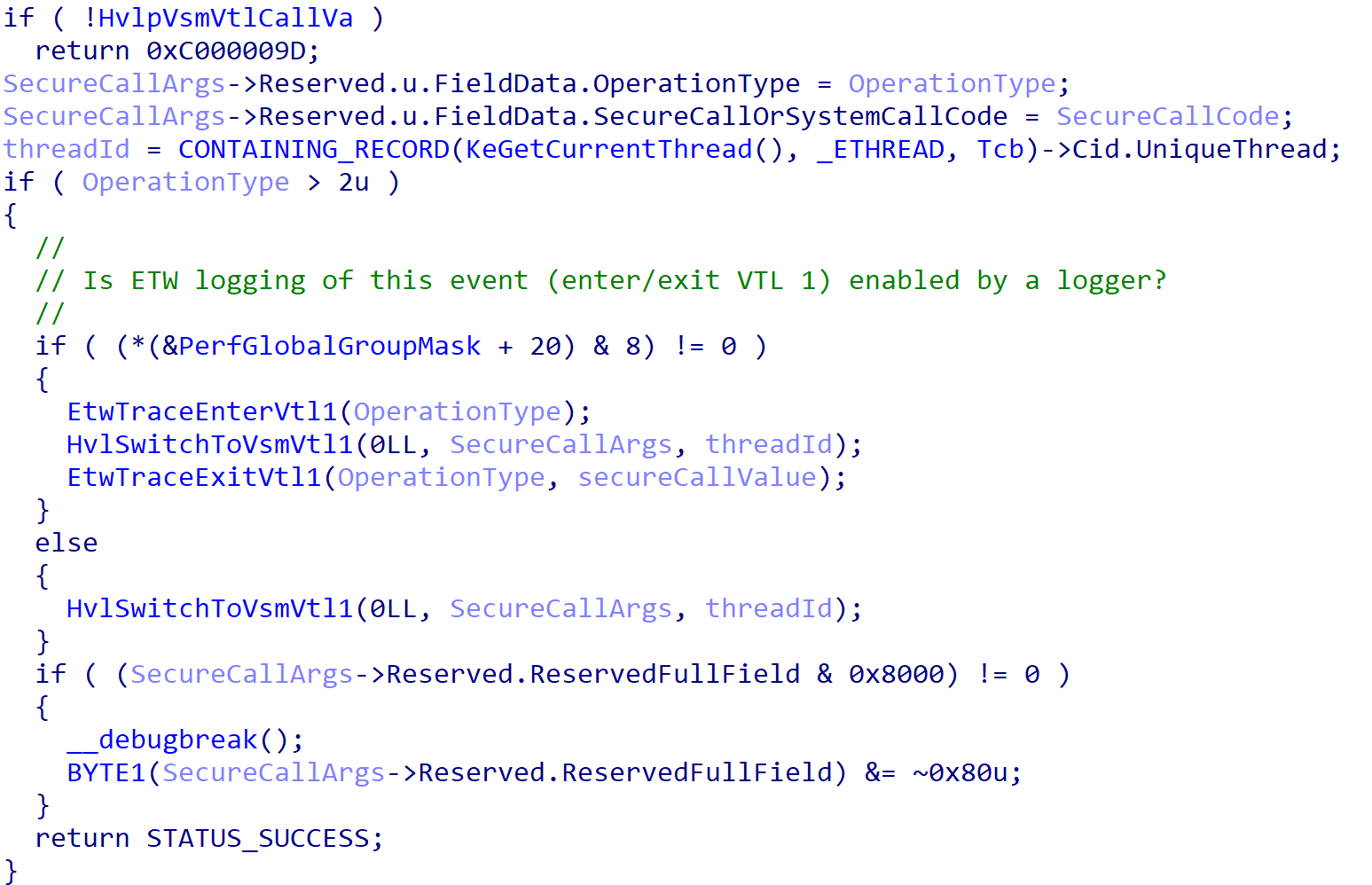

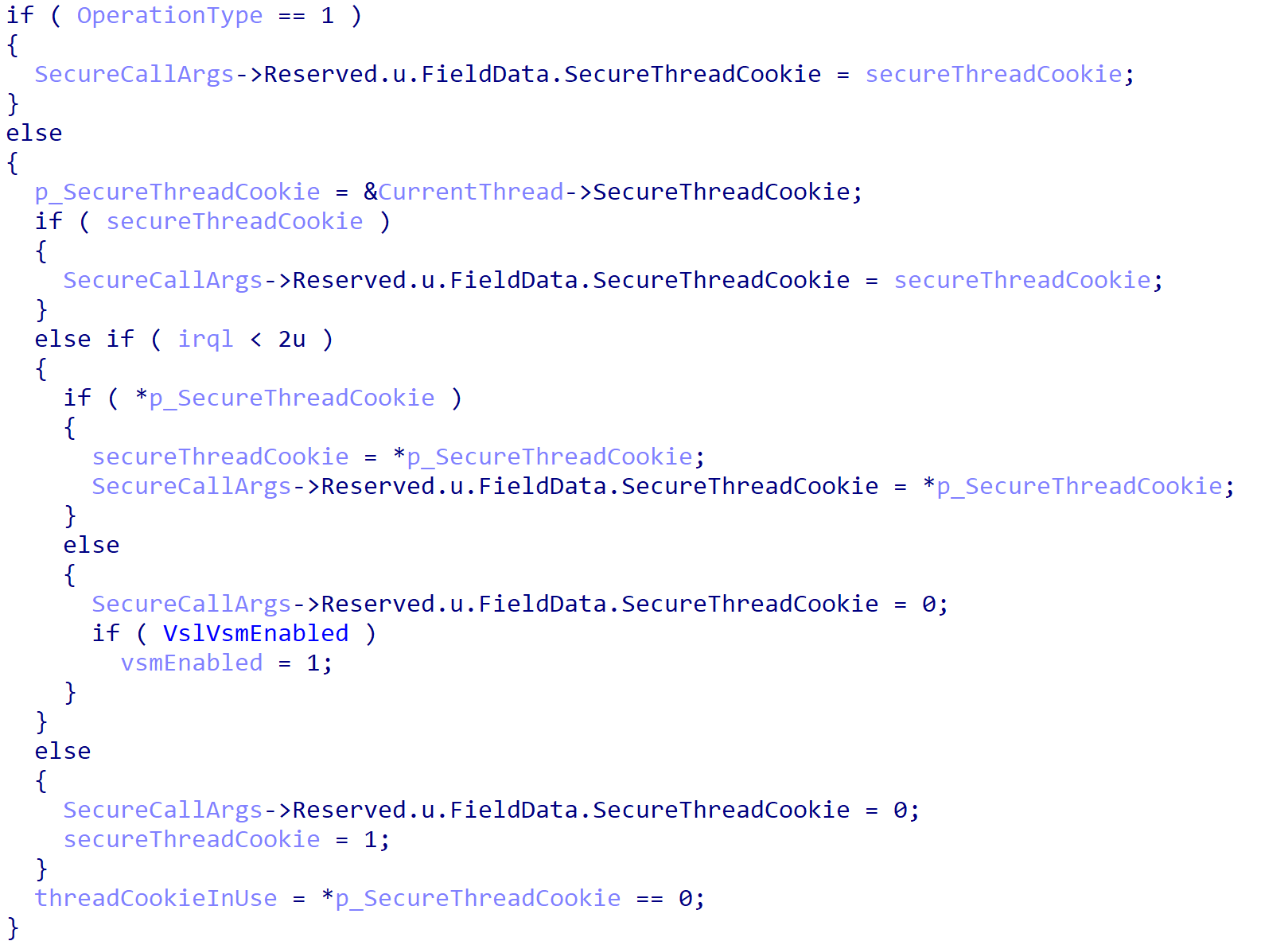

As Windows Internals, 7th Edition Part 2 mentions, and other researchers have noticed, the first argument passed to VslpEnterIumSecureMode is the “operation type”. Almost all of these are set to 2, but other values do exist. 2 seems to indicate “requesting a secure service” or a “secure call”. Additionally, OptionalSecureThreadCookie is unused except for the case of starting a secure thread and calling into an enclave (although, as we will see, a secure thread cookie can still be used even if one is not specified as an argument directly to nt!VslpEnterIumSecureMode).

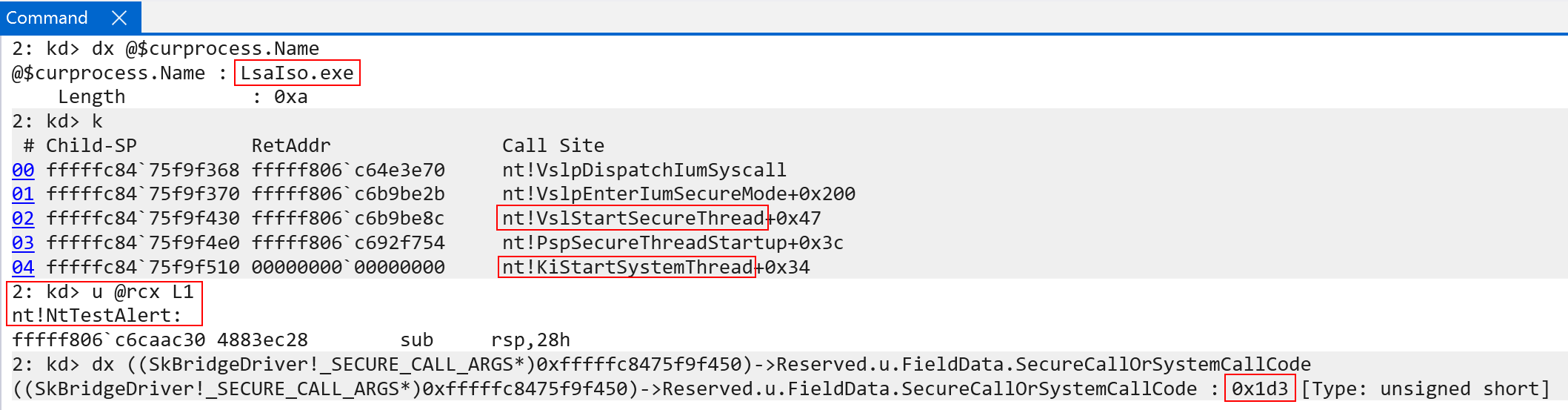

A “secure thread cookie” is created by the Secure Kernel when the NT kernel requests that a secure thread be created. A secure thread is a thread which will run in VTL 1, usually by a trustlet/secure process, but the thread is still created in VTL 0 (and then run in VTL 1, and also may re-enter into VTL 0 as we will see via the “normal call” interface). The Secure Kernel is then responsible for setting up the secure thread and will then, on success, return a “secure thread cookie” back to the NT kernel. This cookie is effectively a “handle” of sorts, and lets the Secure Kernel know (who tracks all known secure threads) which thread a particular secure call needs to be serviced on. Using WinDbg we can identify an example secure thread cookie value:

lkd> dx -g @$cursession.Processes.Where(p => p.Threads.Any(t => t.KernelObject.Tcb.SecureThreadCookie != 0)).Last().Threads.Where(t => t.KernelObject.Tcb.SecureThreadCookie != 0).Select(t => new {Process = (char*)(((nt!_EPROCESS*)(t.KernelObject.ProcessFastRef.Object & ~0xf))->ImageFileName), TID = t.Id, SecureThreadCookie = t.KernelObject.Tcb.SecureThreadCookie})

=======================================================================================

= = (+) Process = (+) TID = SecureThreadCookie =

=======================================================================================

= [0x172c] - 0xffff9e0942b543b8 : "NgcIso.exe" - 0x172c - 0x15 =

=======================================================================================

In this case NgcIso.exe is associated with “Windows Hello” (another feature of Windows is that the biometric authentication can be implemented in VTL 1!) process. In this case the secure thread cookie, managed by the KTHREAD object, is 0x15. This can optionally be provided to the secure call interface to instruct the Secure Kernel to handle a secure call on a particular thread.

nt!VslpEnterIumSecureMode will do a few things, in addition to packaging up the arguments. If the type of operation type is “3” (a request to flush the translation buffers, or TB) an ETW event can be generated for the enter into VTL 1, although we can see later other scenarios also can result in an ETW event for an entry/exit into VTL 1 (you can see my tool Vtl1Mon for more information). If ETW logging is not configured, and the operation is a “flush TB”, nt!HvlSwitchToVsmVtl1 is called directly - which simply issues the hypercall for code 0x11, which is a secure call.

If the operation is not related to flushing the TB it is therefore either a secure call or a normal call (VTL 1 requesting the services of VTL 0). In the case of it being a normal or secure call, the appropriate secure thread cookie is specified (if necessary).

One of the most common scenarios for a “normal” call is a VTL 1 secure process requesting the services of a system call that is not implemented in VTL 1 (and, thus, VTL 0 is needed). In these cases a dedicated secure thread has previously been created by a secure process. This secure thread is “running” in VTL 0 in a loop that can be “broken” when VTL 1 requests a normal call.

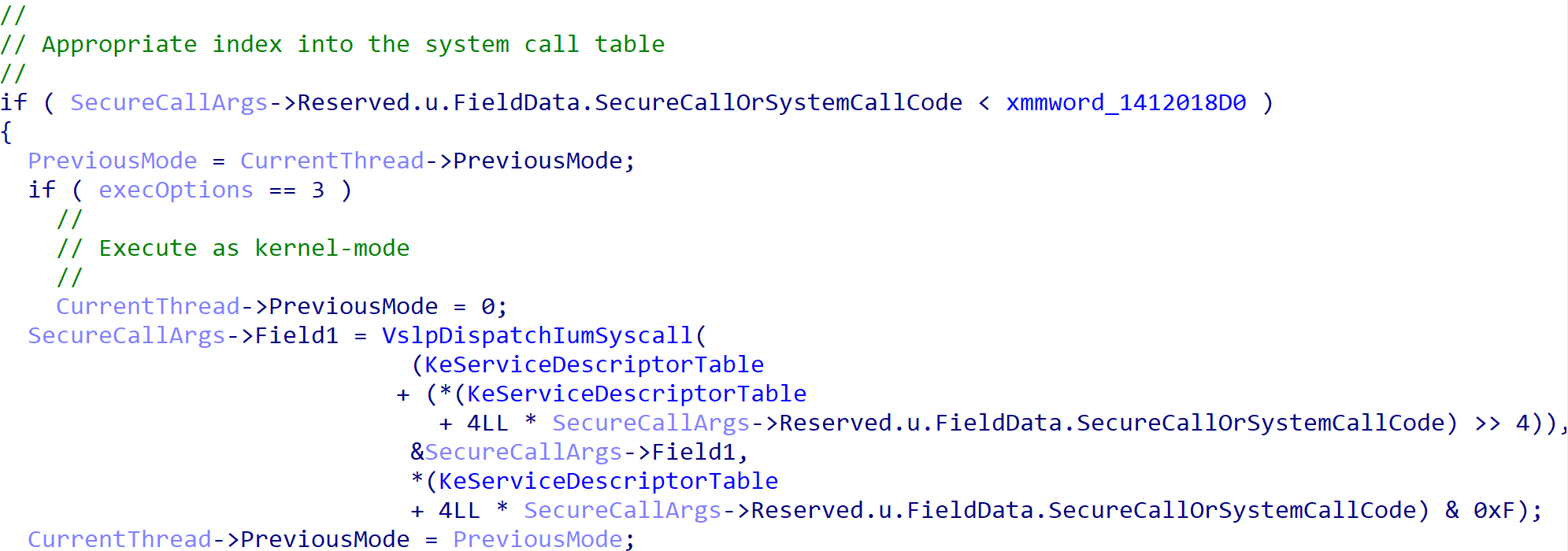

In the above example LsaIso.exe, a secure process running in VTL 1, requested that the system call NtTestAlert be issued (which is system call number 0x1d3 on my machine). This is done by the secure thread, which has now been instructed to service the normal call, by issuing a call through nt!VslpDispatchIumSyscall. In this case an appropriate index into the system service table is used to access a target system call and invoke it (by calling the function, which is passed as the first argument to nt!VslpDispatchIumSyscall as a function pointer). As a point of contention, if a thread cookie is in use APCs are disabled for the target thread.

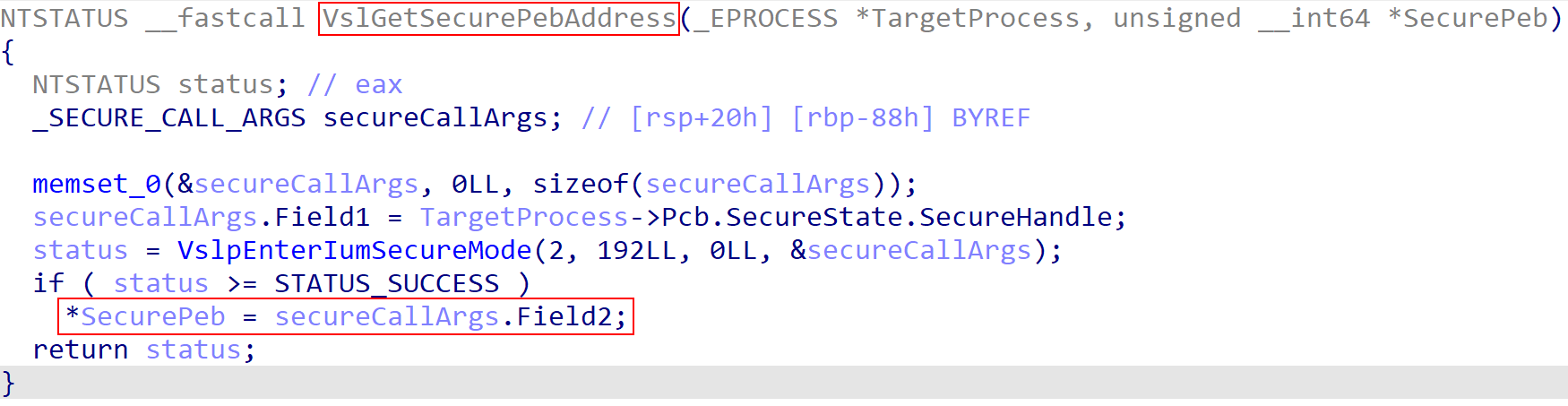

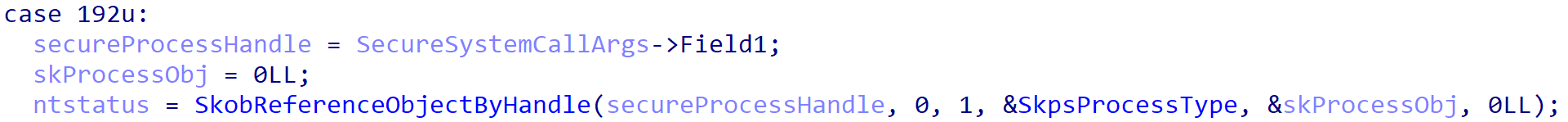

When the secure call (which we are focusing on in this blog) has finished, optional output may be returned to the caller. An example is a call to retrieve the “secure PEB” of a process. Because a “secure process” technically runs in VTL 1, its memory is inaccessible from VTL 0. Due to this, even items like the PEB have special wrappers retrieving the location of items like the PEB. The output, from VTL 1, is returned to the caller through one of the input fields (which can “double” as an input and output field).

This sums up the underlying mechanism for issuing a secure call.

Common Secure Call Patterns

There are many common patterns one will start to notice when dealing with secure calls, specifically leveraging MDLs, or Memory Descriptor Lists. In a previous blog post I talked about one of the existing secure calls related to image validation which leverages MDLs. Effectively some of the parameters of the secure calls are “encapsulated” as MDLs. There is more detail in the aforementioned blog link I provided in this section of the post, but effectively the parameters are encapsulated as MDLs on the VTL 0 side, to lock them into physical memory, and then on the VTL 1 side the MDL is validated (by actually creating a second MDL that describes the input MDL), then mapping the VTL 0 MDL into VTL 1, and then using the mdl->MappedSystemVa to process the parameter. VTL 0 is usually responsible for providing the virtual address of the MDL in VTL 0 and the physical page (PFN) backing the MDL.

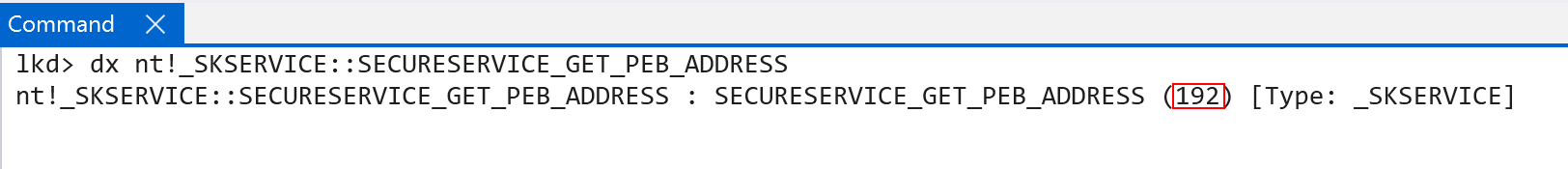

Additionally a common pattern is the use of “secure handles”. These are typically found in the form of processes and threads, and also images (section objects). These handles usually start with 0x140000000. They are, just like “normal handles”, indexes into tables which manage the secure objects in VTL 1. An example is the “secure PEB” retrieval secure call. A list of all the valid secure calls can be found through the nt!_SKSERVICE enum in the symbols.

We then can see in the handler in VTL 1 a call to securekernel!SkobReferenceObjectByHandle is made, specifying the user-provided secure process handle (found in the EPROCESS object in VTL 0). The result is the Secure Kernel “version” of a process, many times referred to as an “SKPROCESS” object.

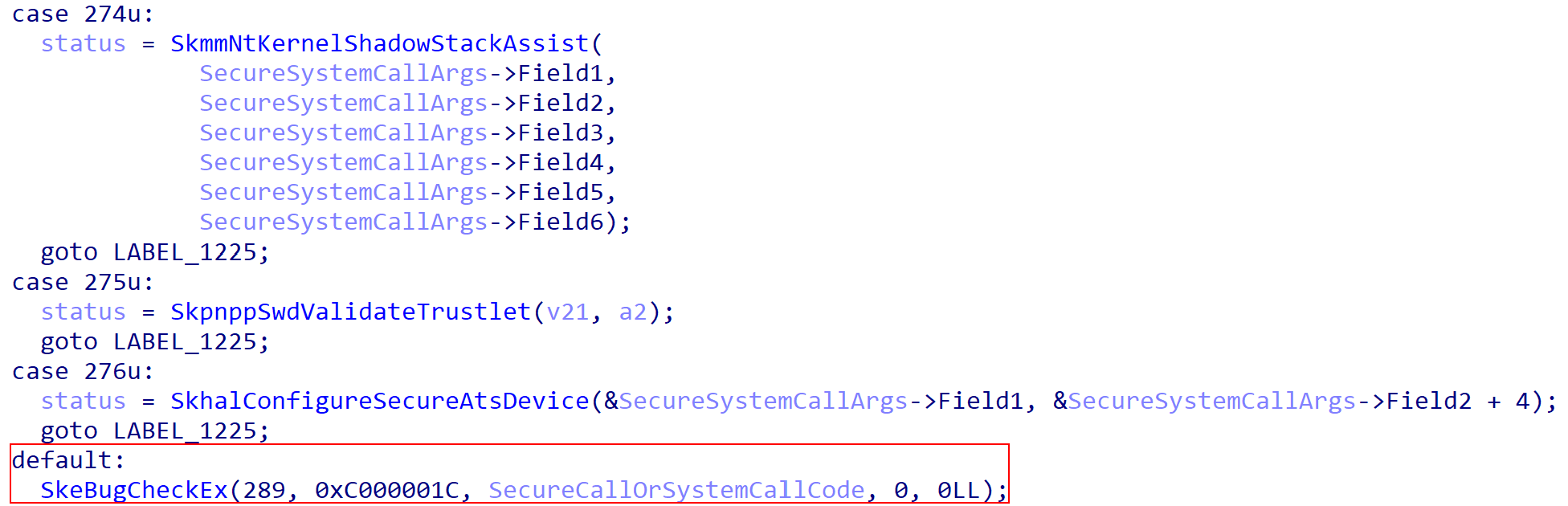

Lastly, it is important to know (especially if one is “fuzzing” the secure call interface) that if you issue any invalid secure call operation, your machine will crash. When I say invalid, I mean providing a numerical secure call value that is not supported by SK (you can validate this via the nt!_SKSERVICE enum).

Issuing Your Own Secure Calls

The point of this entire post, besides outlining the interface between VTL 0 requesting the services of VTL 1, is to introduce a software package I am releasing called SkBridge. SkBridge uses a driver and a user-mode client to allow you to issue your own secure calls! As I have mentioned in this post, most secure calls are made inline of the kernel, with the parameters not being controllable. With this tool, it is possible to issue your own secure calls!

As I have mentioned in this post, there is a lot of nuance with secure calls. It is not as simple as “providing parameters” to the Secure Kernel, as some parameters are not even accessible through documented means (like extracting a secure thread/process handle). Additionally, there is the overhead of needing to encapsulate some parameters as MDLs, converting virtual-to-physical addresses, extracting section objects, secure handles, and also using a specific thread’s secure thread cookie. The project contains a few examples in Examples.cpp in the SkBridgeClient project. Please read the README for more details!

Conclusion

I had started this work a few weeks ago, but got side tracked when I realized it is possible to log secure call requests through ETW. This caused the release of Vtl1Mon. I am hoping that the SkBridge project and Vtl1Mon together can help researchers interface with the Secure Kernel! My hope is this post was either entertainment value or informative. Thank you very much!