Windows ARM64 Internals: Pardon The Interruption! Interrupts on Windows for ARM

Introduction

Recently, I posted a blog which introduced some building blocks related to Windows on ARM (WoA) systems. I have always “known” that interrupts are fairly architecture-specific, and that the implementation of an “interrupt schema” can differ based on this notion. Given this, I thought it would be interesting to investigate the interrupt functionality surrounding WoA systems.

In this blog post, there are likely going to be many omissions - including the fact that (Generic Interrupt Controller) GICv4 systems allow the direct injection of virtual interrupts (my WoA system, for instance, is only on GIC version 3), and many other nuances surrounding virtualization and interrupts in general (although we will touch on virtualization and Secure Kernel “secure interrupts”).

Lastly, this blog post is not meant to be a regurgitation of the existing ARM documentation about low-level interrupt details - although certainly some of this knowledge will be required, and is also outlined in this blog where applicable. This blog, instead, is focused on the theme of a previous blog I did on ARM64 Windows internals - showcasing the basics of ARM64 to Windows researchers who come from an x64 background, like myself, and to outline the differences between x64 and ARM64 interrupt dispatching on Windows systems.

Generic Interrupt Controller (GIC) Overview

One of the main differences between the traditional Intel-based x86 architecture and ARM is the employment, by ARM, of the Generic Interrupt Controller - or GIC. The Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller (APIC) is the controller which most are probably familiar with, who come from a Windows background. This is because this is Intel’s family of interrupt controllers - with most Windows machines running on Intel.

The GIC, on ARM, has seen several iterations. The Surface Pro machine in which this analysis was performed leverages GICv3. However - ARM now has documentation for GICv5. This was announced a few months ago by ARM. This section of the blog is just meant to introduce the basics, and the curious reader should visit the ARM documentation for more information.

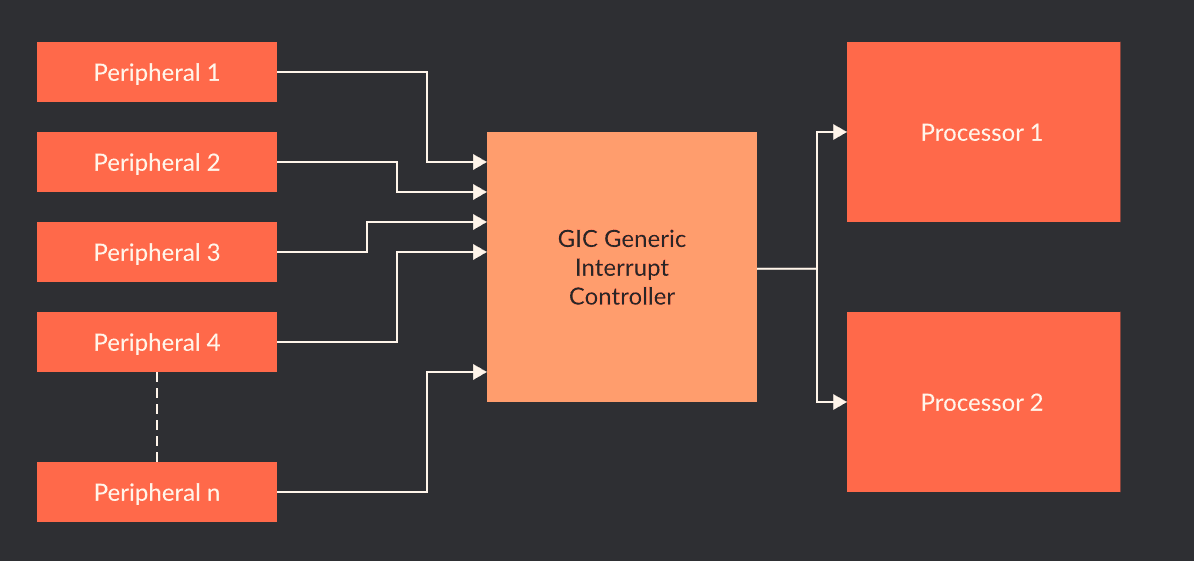

The main purpose of the implementation of a GIC on an ARM system is a standardized way to handle interrupts. The below image, from ARM, provides a high-level overview of GIC interrupt delivery.

This section of the blog will not act as a “glossary” of terms surrounding GIC features. ARM provides documentation surrounding lower-level details. For our purposes, it is - however - worth mentioning the following specifically surrounding what is present in GICv3 (although not necessarily new to GICv3):

- There are two types of interrupts: IRQ and FIQ

- IRQ is a standard interrupt request at normal priority.

- FIQ is a fast interrupt request which is higher priority than an IRQ.

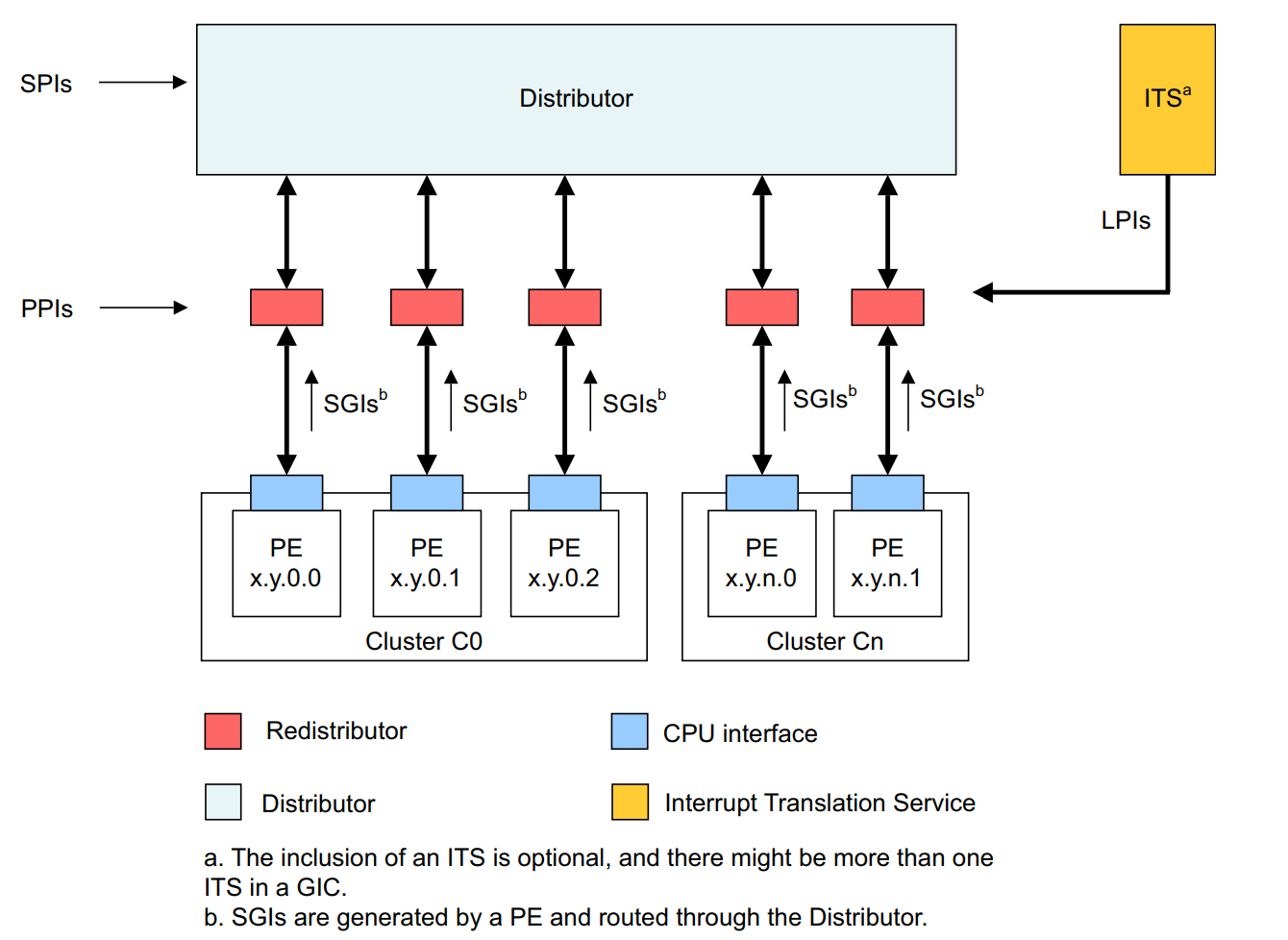

- There are four main “sources” of interrupts:

- External (Shared Peripheral Interrupt, or SPI). This is external in the sense that the interrupt can be delivered to any processor.

- Internal (Private/Per-Processor Peripheral Interrupt, or PPI). This is private to a particular processor. An example of a PPI would be a performance interrupt being generated on a particular processor. The PMU is a per-CPU construct and a target’s CPU can be configured for generation of performance-related information in which an interrupt is generated when certain conditions are true - resulting in a PPI.

- Software-based (Software Generated Interrupt, or SGI). The “ARM” version of an IPI - or Inter-processor interrupt (when a core sends an interrupt to another core)

- Locality-specific (Locality-specific Peripheral Interrupt, or LPI): These are always message-based interrupts which can be generated from an Interrupt Translation Services, or ITS.

- Although Windows, as mentioned in a previous blog post, doesn’t really use TrustZone with VBS enabled (VTLs provide non-secure/secure world functionality) - interrupts are also divided between “secure” and “non-secure” (related to TrustedZone security states)

- A GIC allows for providing virtual interrupt functionality (vGIC) for hypervisors (with nuances based on the GIC version. More on this later.)

In addition to handling interrupts which fire from an “interrupt signal”, from hardware (referred to sometimes as hardware “buzzing” or “poking” the interrupt controller) GICs also support message-based interrupts. The delivery mechanism for these interrupts vary slightly (more on this later). Given that each interrupt source are made up of multiple interrupt IDs (INTIDs) (e.g., interrupt IDs 0-15 are SGIs, 16-31 are PPIs, etc.) this allows not every single ID to need to be physically wired.

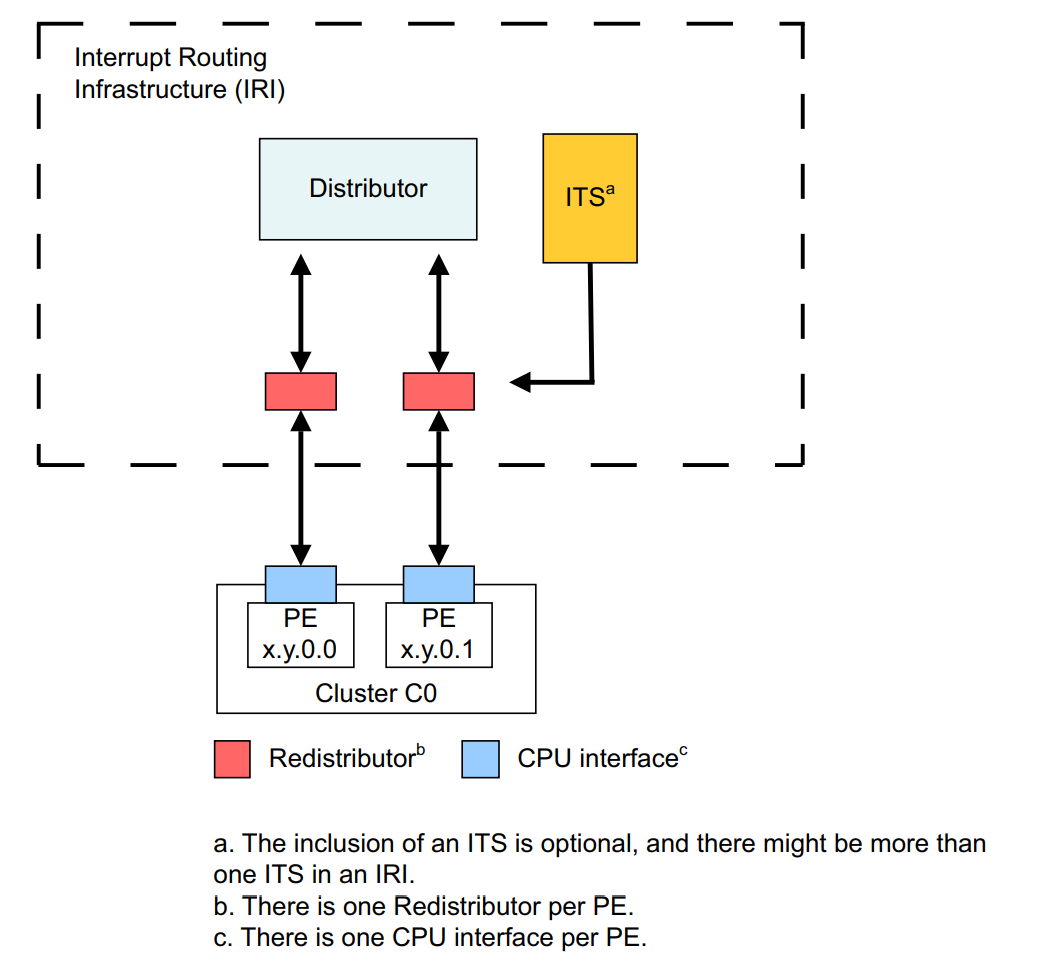

Notice above we refer to interrupt sources - which are represented by a particular INTID - which maps to an “interrupt line” (with a particular “group” of sources, e.g., SPI, PPI, etc.). Interrupts “come” from interrupt sources. Lastly, before we get into the Windows implementation, let’s summarize a four of the important structures in the GIC architecture which are collectively referred to as the Interrupt Routing Infrastructure, or IRI. The IRI and interrupt-routing scheme, taken from the Arm Generic Interrupt Controller Architecture Specification, looks as follows.

GIC Distributor

The GIC distributor is the “brain” of the interrupt schema - and all physical interrupt sources are wired to this component. It is a physically present on a particular SoC (system on a chip, which is how ARM integrates the CPU/GPU/memory controllers/peripherals/etc. into a “single chip”) and it is always accessible via physical memory and not a system register (but the Windows kernel also maps it into virtual memory). There is a single distributor structure on a system.

The distributor primarily prioritzes and distributes physical interrupts to the redistributors (and CPU interfaces). This is especially true for SPIs, which are “external” to a particular CPU in the sense that the distributor must route the interrupt to the specific CPU.

The distributor is involved in software-generated interrupts (like IPIs, even though the interrupts originate from a particular processor) and facilitates routing. However, for interrupts specific to a CPU (like PPI) the distributor does not need to be involved.

GIC Redistributor

Redistributors are per-CPU structures - and there is only one redistributor per CPU. The redistributor receives SPIs that are routed from the interrupt source to the distributor. Redistributors have a few more “moving parts”, or nuances.

In addition, when software-initialited interrupts (like an inter-processor interrupt requested from software) occur (SGIs), they are generated by both the “issuing” CPU interface and redistributor. From these components, they are then routed to the distributor and then the target CPU’s redistributor and CPU interface receive the interrupt.

PPIs are interrupts which are local to a specific CPU. Because of this, the distributor is not needed at all. The interrupt source interrupt is directly routed to the CPU’s redistributor. Additionally, LPIs are routed to a target redistributor.

GIC CPU Interface

The various CPU interfaces, then, become the mechansim to which a core actually receives an interrupt. There is both a physical CPU interface and a virtual CPU interface present (but for now when we refer to the “CPU interface” we are referring to the physical interface). The CPU interface is accessible through system registers (or memory-mapped interface, but Windows uses the system registers). This means the registers can be used to mask interrupts and control the state of interrupts on the CPU.

GIC Interrupt Translation Services (ITS)

The ITS is an optional (for GICv3, which our machine is using). The ITS has a primary usage - message-based interrupts (MSIs). The ITS, when it is present, is responsible for routing LPIs (which represent message-based interrupts) to a target CPU’s redistributor. They are also responsible for actually translating the MSI request (message-based interrupt) into an LPI.

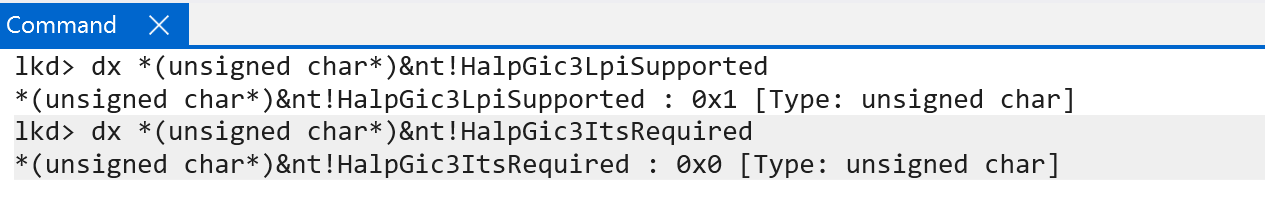

The Surface Pro machine in which this analysis was conducted on does implement an ITS. However, because the OS is virtualized Hyper-V does not expose it to the root partition (thank you to Longhorn for pointing this out). GIC4 requires an ITS because GIC4 needs to support virtual LPIs due to support for direct injection of virtual interrupts to a VM without involving the hypervisor.

Lastly, the following image summarizes the basic interrupt routine schema - taken once again from ARM documentation.

Windows on ARM Interrupt Initialization And Discovery

Although there are some references to interrupt functionality before it, we will start at nt!HalpInitializeInterrupts. This function is responsible for most of the interrupt discovery and initialization that we care about. nt!HalpInitializeInterrupts receives a single parameter - the loader parameter block, from the bootloader, represented by the nt!_LOADER_PARAMETER_BLOCK structure.

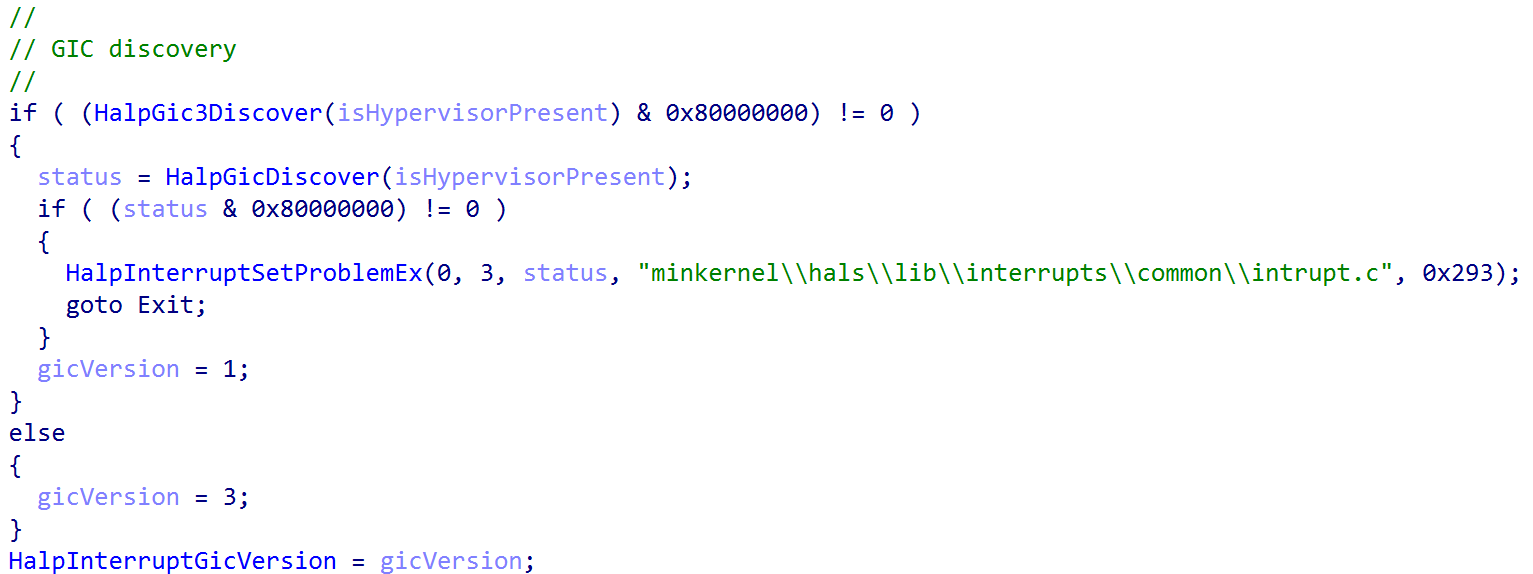

One of the first things this function does is to perform “GIC” discovery. The kernel will attempt to first discover GICv3, and will “default” to checking if GICv1 is available.

As a point of contention,

nt!HalSetInterruptProblemaccepts a parameter to a value from theINTERRUPT_PROBLEMenum. For ARM devices, the following are valid values, which can help aid in debugging/determining what is occuring. For example, in this case the error from the above image denotes that discovery is occuring (InterruptProblemFailedDiscovery):

lkd> dt nt!_INTERRUPT_PROBLEM

InterruptProblemNone = 0n0

InterruptProblemMadtParsingFailure = 0n1

InterruptProblemNoControllersFound = 0n2

InterruptProblemFailedDiscovery = 0n3

InterruptProblemInitializeLocalUnitFailed = 0n4

InterruptProblemInitializeIoUnitFailed = 0n5

InterruptProblemSetLogicalIdFailed = 0n6

InterruptProblemSetLineStateFailed = 0n7

InterruptProblemGenerateMessageFailed = 0n8

InterruptProblemConvertIdFailed = 0n9

InterruptProblemCmciSetupFailed = 0n10

InterruptProblemQueryMaxProcessorsCalledTooEarly = 0n11

InterruptProblemProcessorReset = 0n12

InterruptProblemStartProcessorFailed = 0n13

InterruptProblemProcessorNotAlive = 0n14

InterruptProblemLowerIrqlViolation = 0n15

InterruptProblemInvalidIrql = 0n16

InterruptProblemNoSuchController = 0n17

InterruptProblemNoSuchLines = 0n18

InterruptProblemBadConnectionData = 0n19

InterruptProblemBadRoutingData = 0n20

InterruptProblemInvalidProcessor = 0n21

InterruptProblemFailedToAttainTarget = 0n22

InterruptProblemUnsupportedWiringConfiguration = 0n23

InterruptProblemSpareAlreadyStarted = 0n24

InterruptProblemClusterNotFullyReplaced = 0n25

InterruptProblemNewClusterAlreadyActive = 0n26

InterruptProblemNewClusterTooLarge = 0n27

InterruptProblemCannotHardwareQuiesce = 0n28

InterruptProblemIpiDestinationUpdateFailed = 0n29

InterruptProblemNoMemory = 0n30

InterruptProblemNoIrtEntries = 0n31

InterruptProblemConnectionDataBaitAndSwitch = 0n32

InterruptProblemInvalidLogicalFlatId = 0n33

InterruptProblemDeinitializeLocalUnitFailed = 0n34

InterruptProblemDeinitializeIoUnitFailed = 0n35

InterruptProblemMismatchedThermalLvtIsr = 0n36

InterruptProblemHvRetargetFailed = 0n37

InterruptProblemDeferredErrorSetupFailed = 0n38

InterruptProblemBadInterruptPartition = 0n39

nt!HalpGic3Discover begins by enumerating the Advanced Configuration and Power Interface (ACPI) table named “APIC”. In order for there to less work for the hardware abstraction layer (HAL) Windows effectively requires that ARM64 systems which run Windows require ACPI.

ACPI is a specification which is used to allow hardware to describe the interfaces which are available for usage by software. ACPI is particularly relevant to us because it describes interrupt functionality on the system. After all, interrupts are not just a software construct - the actual computer chips have physical wiring used for many interrupt operations, as an example. As such, the ACPI interface exposes a series of tables which allow the OS to become enlightened about the actual hardware configuration of the machine - including the interrupt configuration.

The ACPI “APIC” table really refers to the Multiple APIC Description Table, or MADT. Although APIC is the name used, as Intel-based systems have dominated for so long, the latest versions of ACPI (5.0 and beyond) have added descriptors for GIC - which is what ARM-based systems use (not APIC). The MADT, as we will refer to it, is responsible for describing the interrupt functionality of the system - specific describing the GIC and also GIC distributor (which we have previously mentioned).

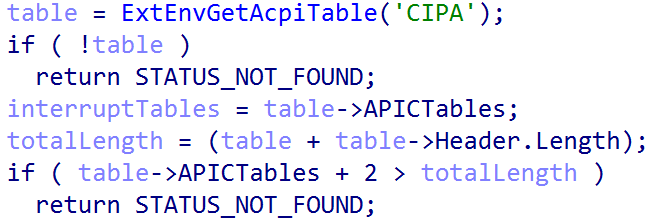

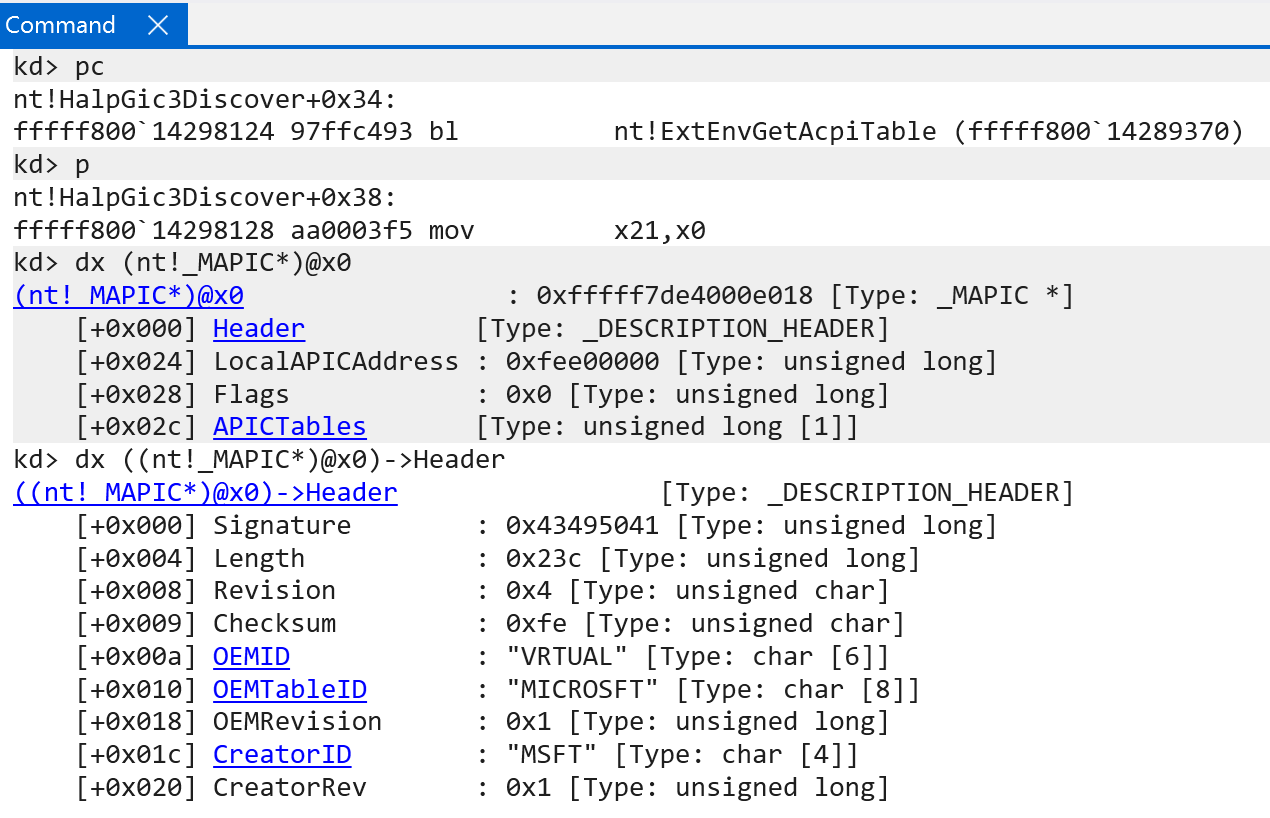

The nt!ExtEnvGetAcpiTable, in this case, returns a pointer to an nt!_MAPIC structure - which represents the MADT, and contains the following layout. You can cross-reference this layout with the latest ACPI specification from UEFI:

kd> dt nt!_MAPIC -r2

+0x000 Header : _DESCRIPTION_HEADER

+0x000 Signature : Uint4B

+0x004 Length : Uint4B

+0x008 Revision : UChar

+0x009 Checksum : UChar

+0x00a OEMID : [6] Char

+0x010 OEMTableID : [8] Char

+0x018 OEMRevision : Uint4B

+0x01c CreatorID : [4] Char

+0x020 CreatorRev : Uint4B

+0x024 LocalAPICAddress : Uint4B

+0x028 Flags : Uint4B

+0x02c APICTables : [1] Uint4B

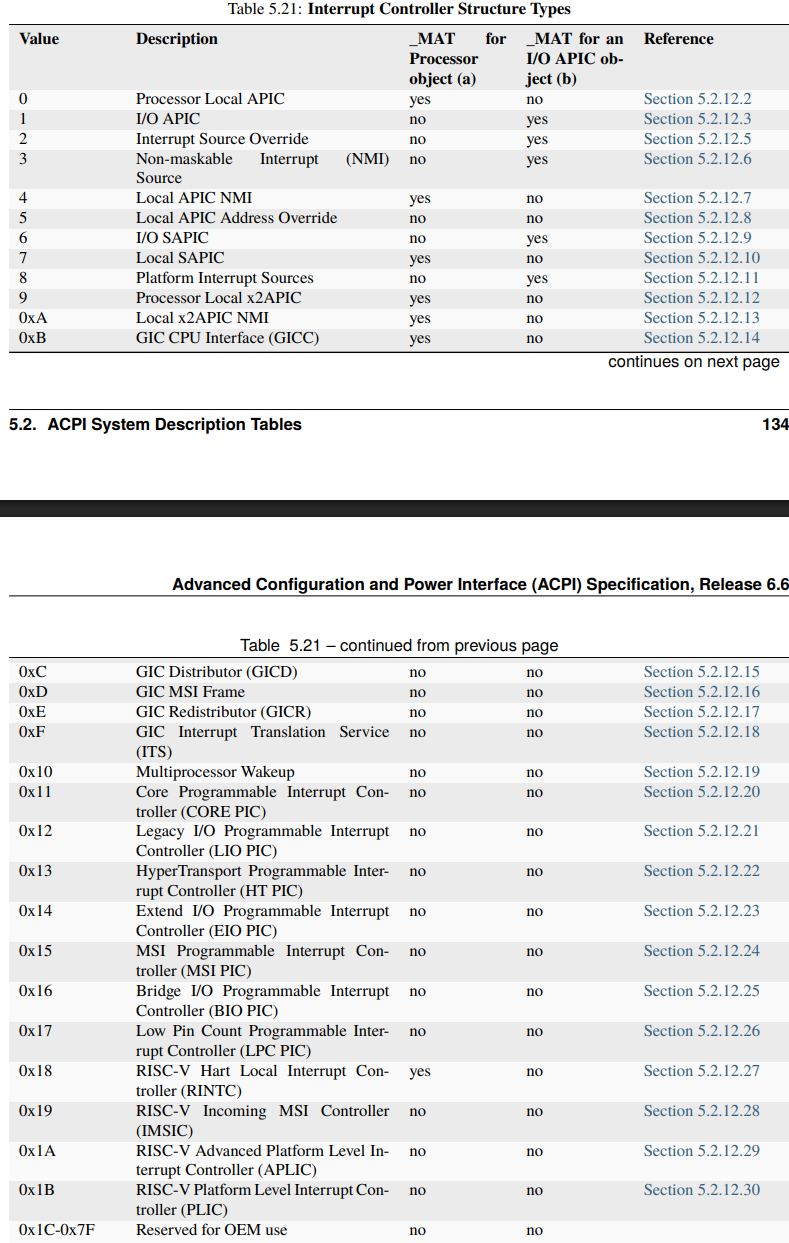

The APICTables member of this structure corresponds to the Interrupt Controller Structure[n] outlined in the official ACPI specification - which refers to a list of interrupt controller structures available on the system.

In this case the nt!_MAPIC structure acts as a header of sorts to describe all of the various interrupt structures which follow - all of which make up the interrupt functionality on the system. WinDbg provides a nice extension which allows us to easily parse-out what functionality is present:

kd> !mapic @x0

MAPIC - HEADER - fffff7de4000e018

Signature: APIC

Length: 0x0000023c

Revision: 0x04

Checksum: 0xfe

OEMID: VRTUAL

OEMTableID: MICROSFT

OEMRevision: 0x00000001

CreatorID: MSFT

CreatorRev: 0x00000001

MAPIC - BODY - fffff7de4000e03c

Local APIC Address: 0xfee00000

Flags: 00000000

GIC Distributor

Reserved1: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000000

Controller Addr: 0x00000000ffff0000

GSIV Base: 0x00000000

Reserved2: 0x00000000

Version: 0x00000003

Processor Local GIC

Reserved: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000000

ACPI Processor ID: 0x00000001

Flags: 0x00000001

Parking Proto Version: 0x00000000

Perf Interrupt GSI: 0x00000017

Parked Addr: 0x0000000000000000

Controller Addr: 0x0000000000000000

GICV: 0x0000000000000000

GICH: 0x0000000000000000

VGIC Maintenance Intr: 0x00000000

GICR Base Addr: 0x00000000effee000

MPIDR: 0x0000000000000000

PowerEfficiencyClass: 0x00

SPE overflow interrupt GSI (PMBIRQ): 0x00

Processor is Enabled

Processor Local GIC

Reserved: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000000

ACPI Processor ID: 0x00000002

Flags: 0x00000001

Parking Proto Version: 0x00000000

Perf Interrupt GSI: 0x00000017

Parked Addr: 0x0000000000000000

Controller Addr: 0x0000000000000000

GICV: 0x0000000000000000

GICH: 0x0000000000000000

VGIC Maintenance Intr: 0x00000000

GICR Base Addr: 0x00000000f000e000

MPIDR: 0x0000000000000001

PowerEfficiencyClass: 0x00

SPE overflow interrupt GSI (PMBIRQ): 0x00

Processor is Enabled

Processor Local GIC

Reserved: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000000

ACPI Processor ID: 0x00000003

Flags: 0x00000001

Parking Proto Version: 0x00000000

Perf Interrupt GSI: 0x00000017

Parked Addr: 0x0000000000000000

Controller Addr: 0x0000000000000000

GICV: 0x0000000000000000

GICH: 0x0000000000000000

VGIC Maintenance Intr: 0x00000000

GICR Base Addr: 0x00000000f002e000

MPIDR: 0x0000000000000002

PowerEfficiencyClass: 0x00

SPE overflow interrupt GSI (PMBIRQ): 0x00

Processor is Enabled

Processor Local GIC

Reserved: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000000

ACPI Processor ID: 0x00000004

Flags: 0x00000001

Parking Proto Version: 0x00000000

Perf Interrupt GSI: 0x00000017

Parked Addr: 0x0000000000000000

Controller Addr: 0x0000000000000000

GICV: 0x0000000000000000

GICH: 0x0000000000000000

VGIC Maintenance Intr: 0x00000000

GICR Base Addr: 0x00000000f004e000

MPIDR: 0x0000000000000003

PowerEfficiencyClass: 0x00

SPE overflow interrupt GSI (PMBIRQ): 0x00

Processor is Enabled

Processor Local GIC

Reserved: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000000

ACPI Processor ID: 0x00000005

Flags: 0x00000001

Parking Proto Version: 0x00000000

Perf Interrupt GSI: 0x00000017

Parked Addr: 0x0000000000000000

Controller Addr: 0x0000000000000000

GICV: 0x0000000000000000

GICH: 0x0000000000000000

VGIC Maintenance Intr: 0x00000000

GICR Base Addr: 0x00000000f006e000

MPIDR: 0x0000000000000004

PowerEfficiencyClass: 0x00

SPE overflow interrupt GSI (PMBIRQ): 0x00

Processor is Enabled

Processor Local GIC

Reserved: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000000

ACPI Processor ID: 0x00000006

Flags: 0x00000001

Parking Proto Version: 0x00000000

Perf Interrupt GSI: 0x00000017

Parked Addr: 0x0000000000000000

Controller Addr: 0x0000000000000000

GICV: 0x0000000000000000

GICH: 0x0000000000000000

VGIC Maintenance Intr: 0x00000000

GICR Base Addr: 0x00000000f008e000

MPIDR: 0x0000000000000005

PowerEfficiencyClass: 0x00

SPE overflow interrupt GSI (PMBIRQ): 0x00

Processor is Enabled

MSI Frame

Reserved1: 0x0000

Identifier: 0x00000001

Physical Address: 0x00000000effe8000

Flags: 0x00000001

SpiCount: 0x0024

SpiBase: 0x039d

End of MAPIC.

We can see many structures are present here: the GIC distributor (of which there can only be), the “Processor Local GIC”, which refers to the per-CPU “interfaces” we mentioned earlier. My machine has 6 CPUs and 12 total cores (and we can see there are 6 here. These are represented by the “GIC CPU Interface (GICC) Structure” structure mentioned in the ACPI specification), per-CPU GIC redistributors (GIC Redistributor (GICR) Structure), and a single MSI (GIC MSI Frame Structure) interface.

nt!HalpGic3Discover is then responsible for parsing all of the present interrupt structures and enlightening the kernel about what types of GIC features are supported (are LPIs supported, are Interrupt Translation Services required, how many enabled GIC CPU interfaces are there, and other items). nt!HalpGic3Discover receives a single parameter - a value from the EXT_ENV enumeration that denotes more information about the current operating environment - and is passed on down the initialization stack. In our case, for instance, the operating environment is that of ExtEnvHvRoot - because I am on a machine which has VBS enabled and, therefore, the Windows OS resides in the root partition. This means that the GIC needs to interact with the root partition. As we will see later, especially in the case of virtual interrupts, knowing the execution environment is important.

lkd> dt nt!_EXT_ENV

ExtEnvUnknown = 0n0

ExtEnvNativeHal = 0n1

ExtEnvHvRoot = 0n2

ExtEnvHvGuest = 0n3

ExtEnvHypervisor = 0n4

ExtEnvSecureKernel = 0n5

As a point of contention, however, dynamic analysis is done in a VM, and so (obviously) the operating environment is that of a guest:

0: kd> dx ((nt!_GIC3_DATA*)0xfffff7f440000a10)->ExtEnv

((nt!_GIC3_DATA*)0xfffff7f440000a10)->ExtEnv : ExtEnvHvGuest (3) [Type: _EXT_ENV]

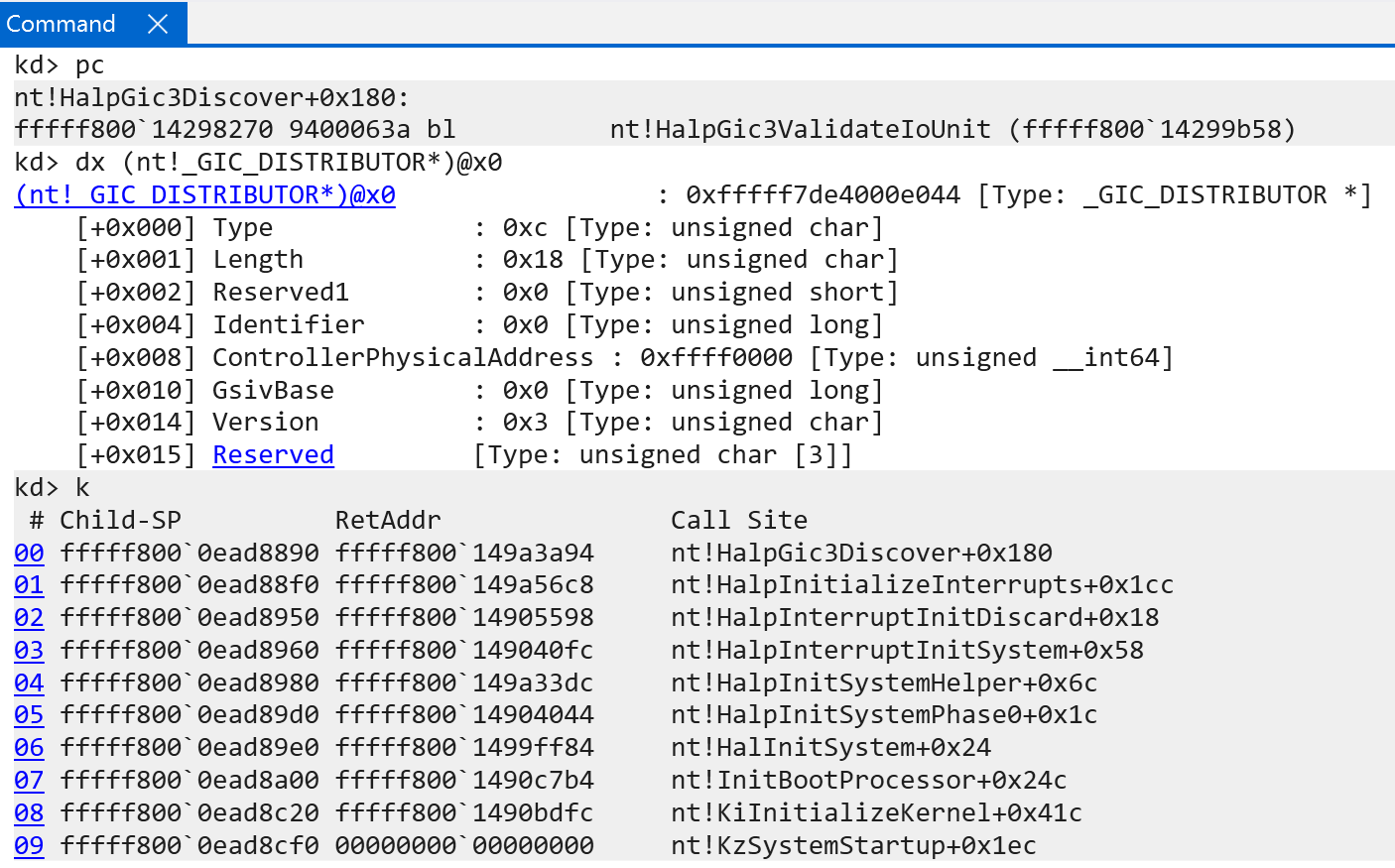

On success, the GIC distributor is then validated via nt!Gic3ValidateIoUnit. As mentioned the single GIC distributor is where all interrupt sources are wired to. This is a very important structure. On Windows, the nt!_GIC_DISTRIBUTOR structure represents the GIC distributor.

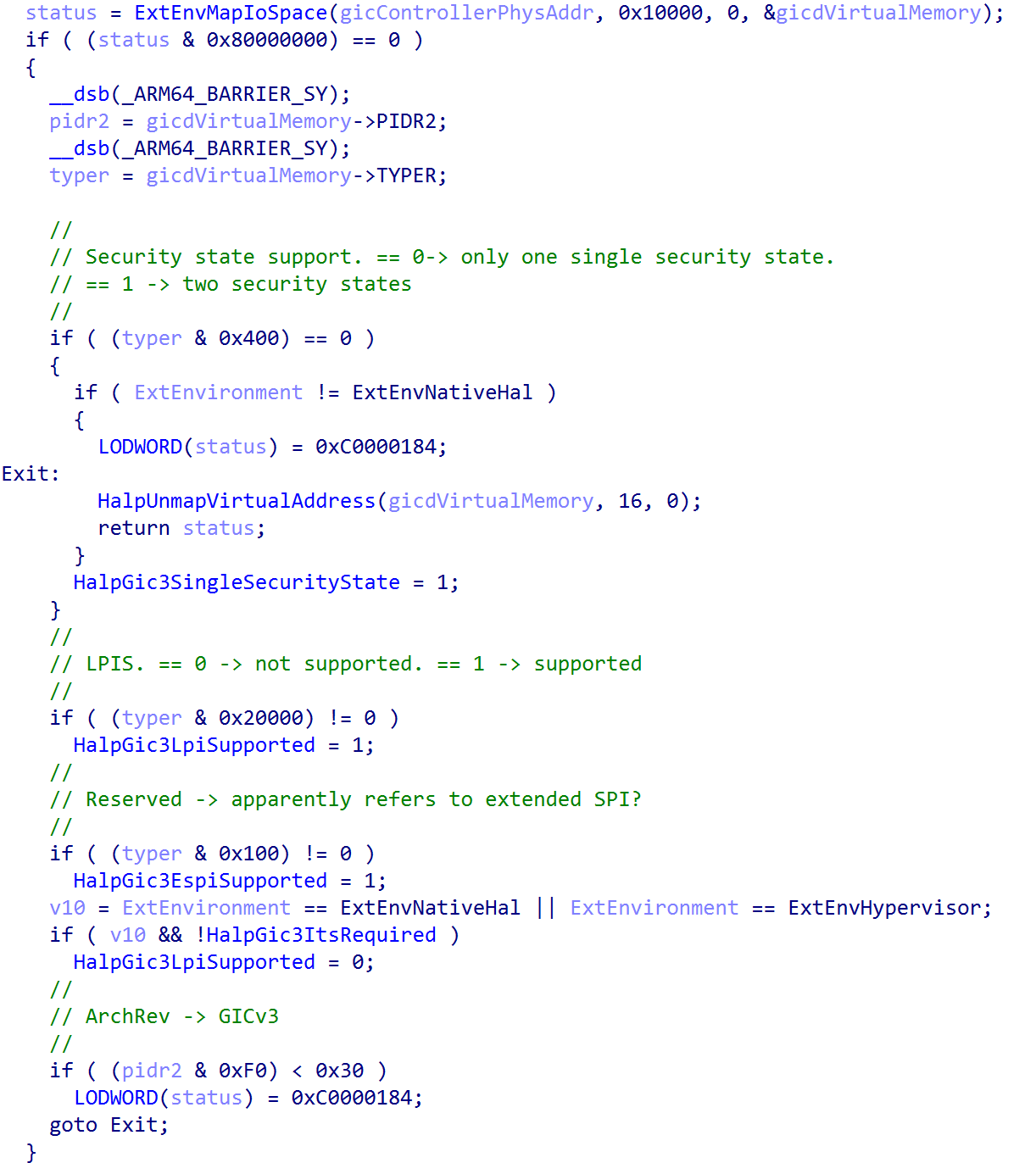

The GIC distributor structure defined by Windows is used to describe the GIC distributor. However, the GIC distributor is actually mapped into physical memory and is accessed on Windows by the ControllerPhysicalAddress member of the nt!_GIC_DISTRIBUTOR structure. This address has a layout of the actual GIC distributor described by ARM here. This structure, which is not in the Windows symbols (I manually added it into IDA) fills out the rest of the “enlightened” data of the kernel - including the number of supported security states, if LPIs are supported (supported - not in use), extended SPI support, and a last GIC version check.

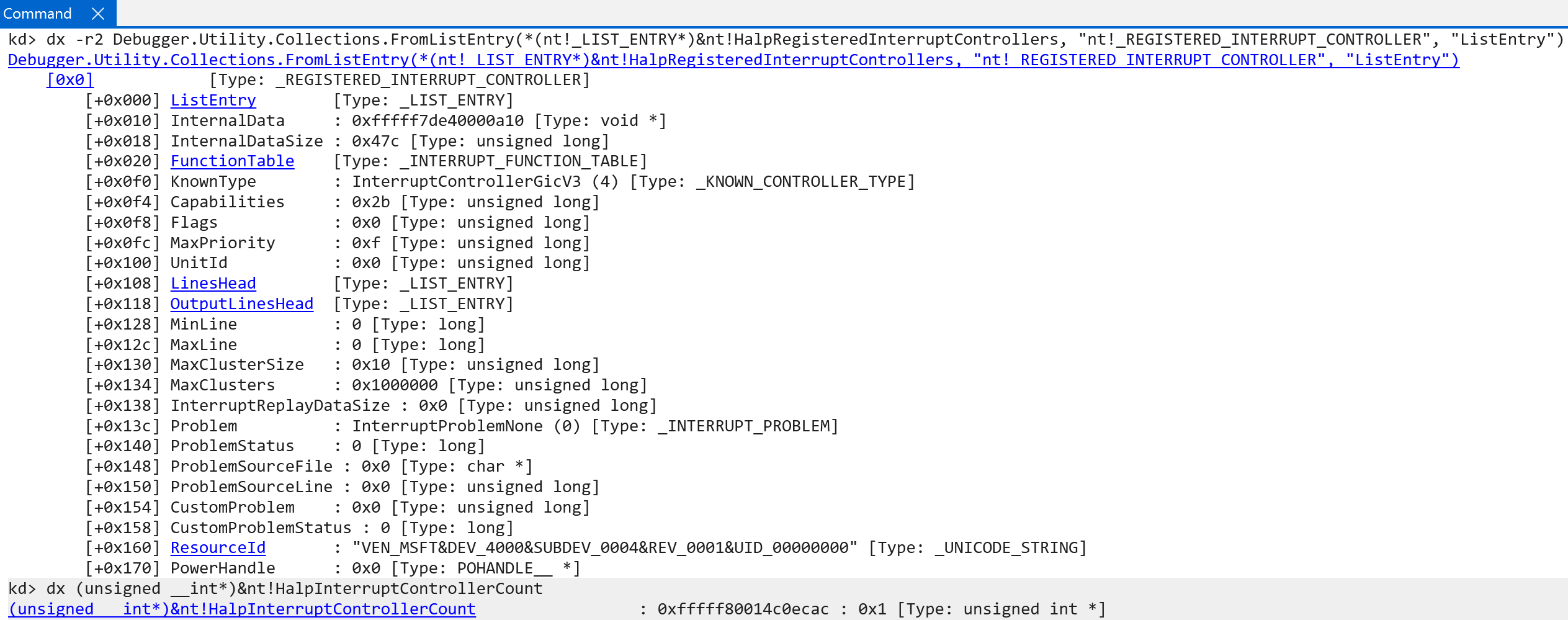

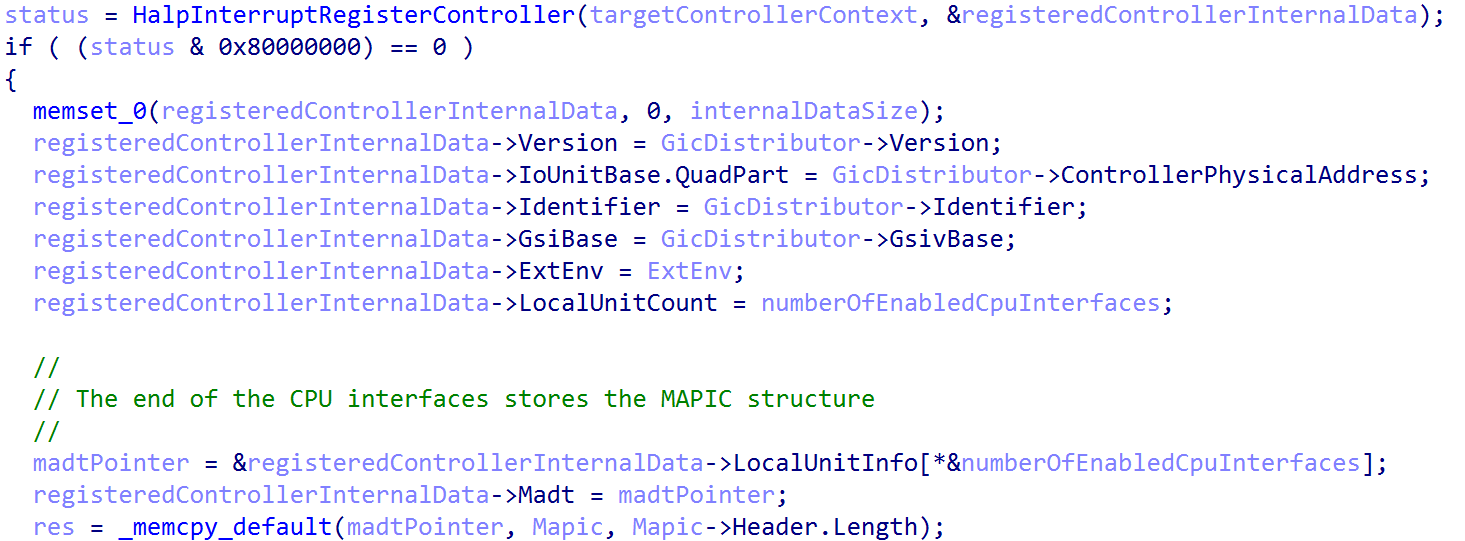

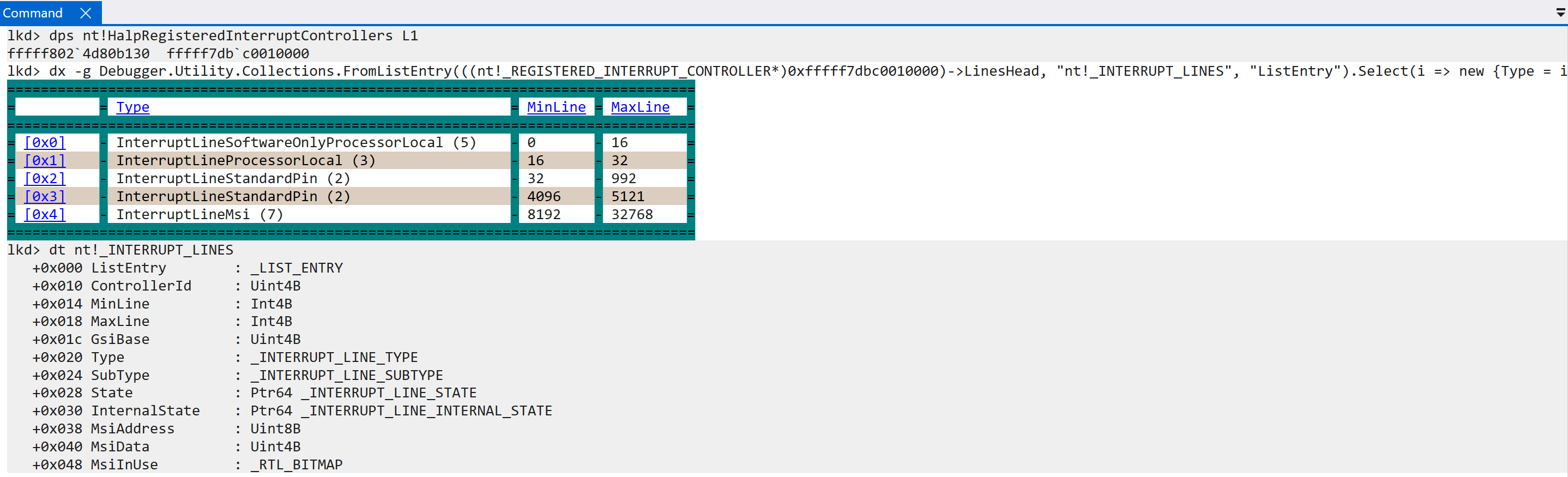

After the GIC is validated by the Windows kernel, the actual interrupt controller is registered with Windows. This is done through the nt!HalpGic3RegisterIoUnit function. This function is responsible for filling out the information which is used to construct the list of registered interrupt controllers on the system. On the machine this analysis was performed on, there was only one registered interrupt controller. This is achieved by filling out an nt!_REGISTERED_INTERRUPT_CONTROLLER structure and adding it to the doubly-linked list of interrupt controllers, managed by the nt!HalpRegisteredInterruptControllers symbol, and also incrementing the count of nt!HalpInterruptControllerCount. Using WinDbg we can actually parse the entire linked list (which contains only one link) to view the contents of the registered interrupt controller.

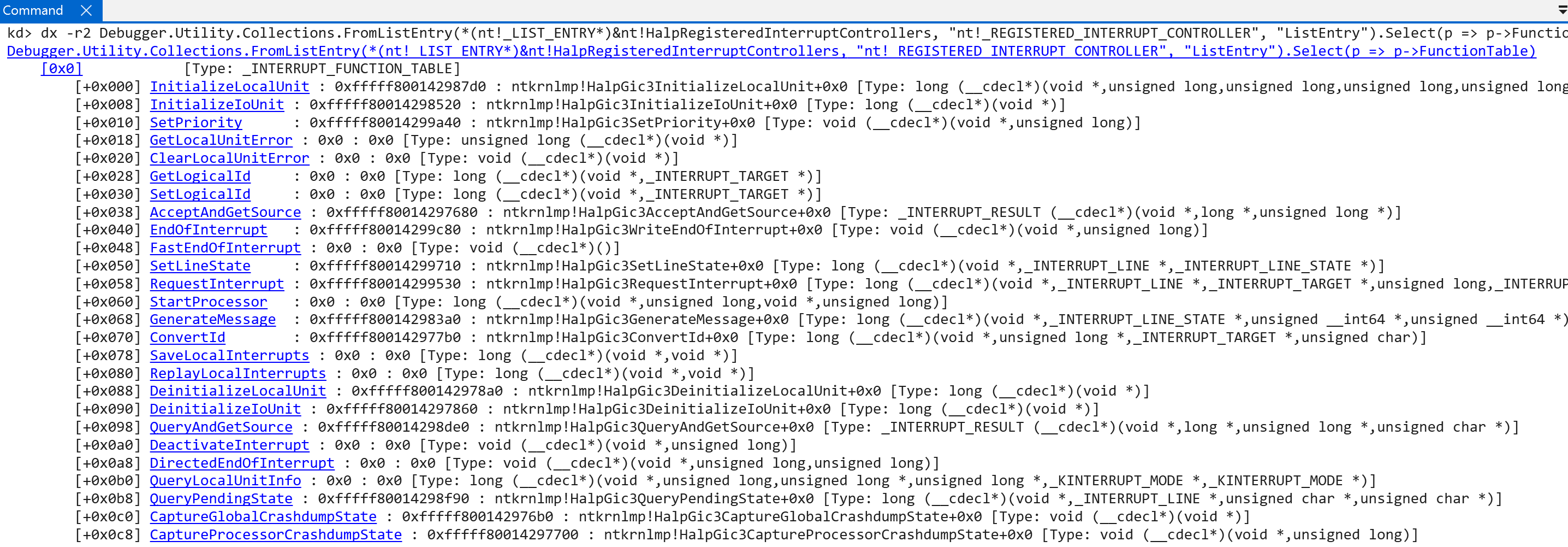

Here we can see, and it should be no suprise, that the KnownType is set to InterruptControllerGicV3 - which seems to indicate that we are looking at the correct structure. This is how Windows goes from interrupt functionality discovery to actually registering an interrupt controller with the OS, from what is available from hardware. The registered interrupt controller also contains a list of functions (represented by the nt!_INTERRUPT_FUNCTION_TABLE structure) which a list of functions which allow further configuration of the interrupt controller and/or interaction from the HAL. These are not the “interrupt handler” functions.

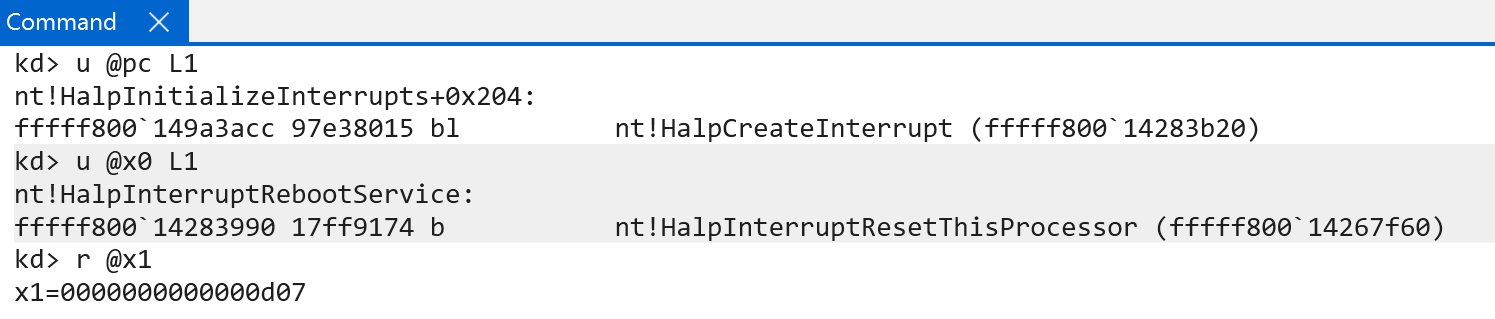

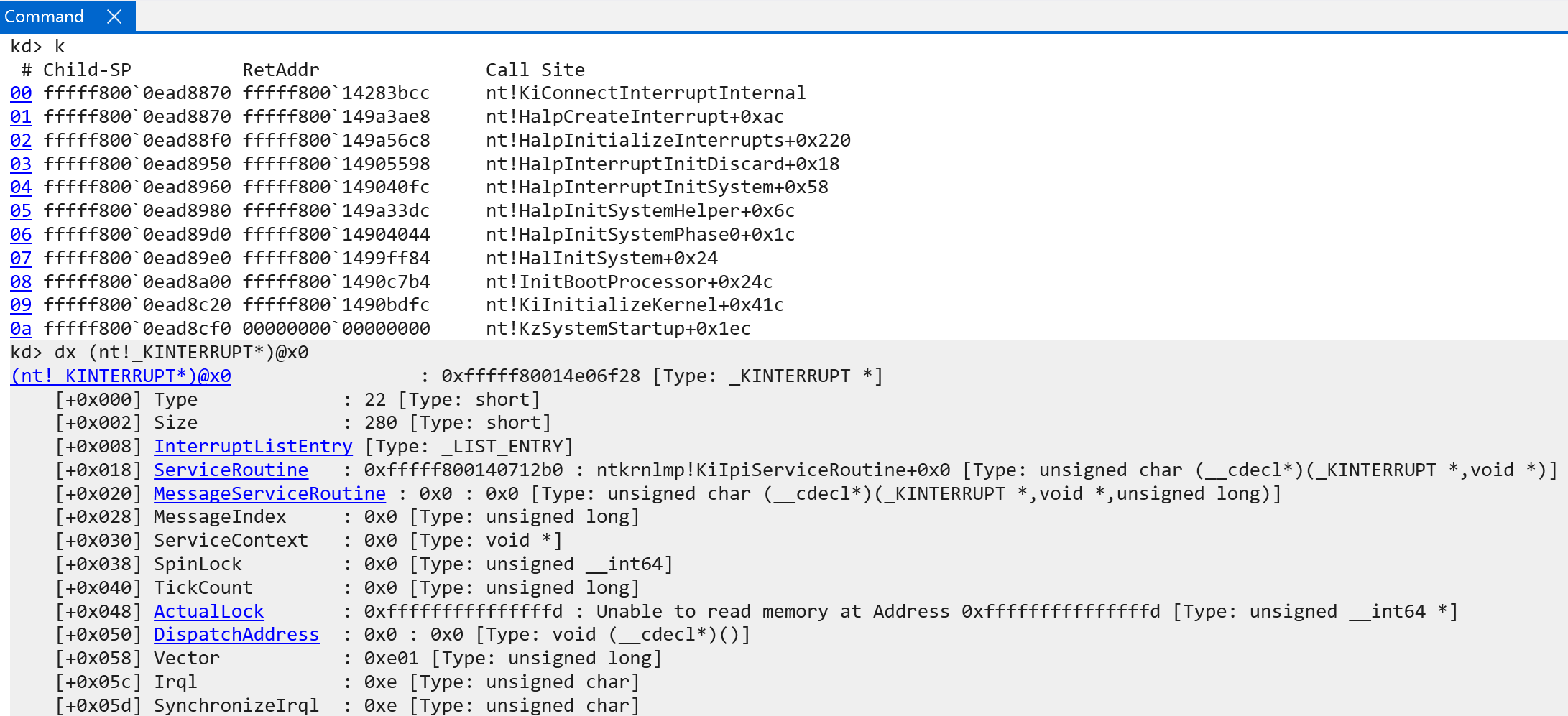

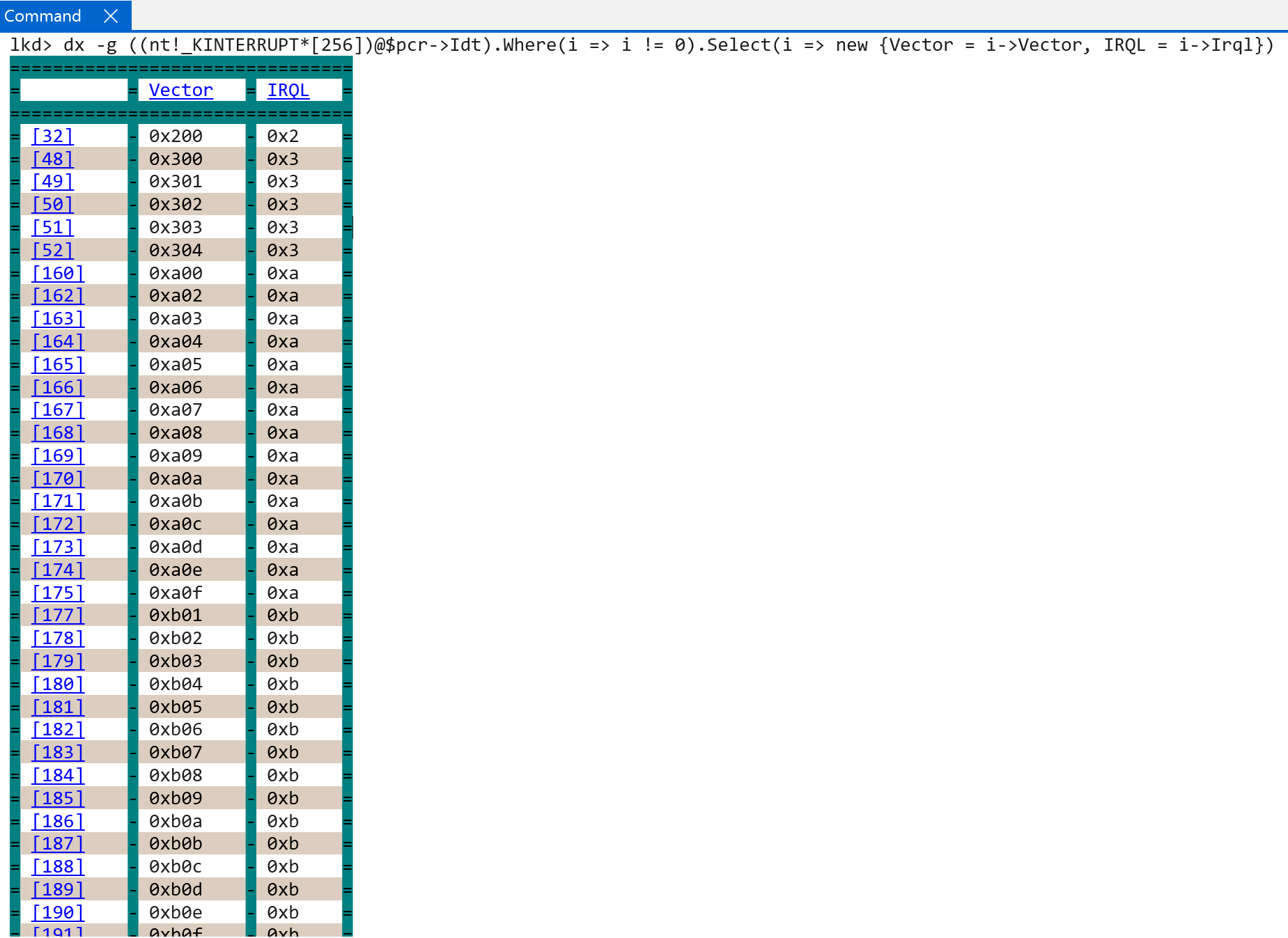

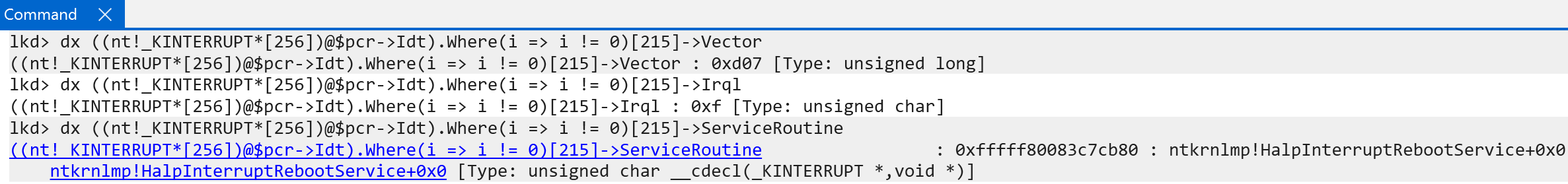

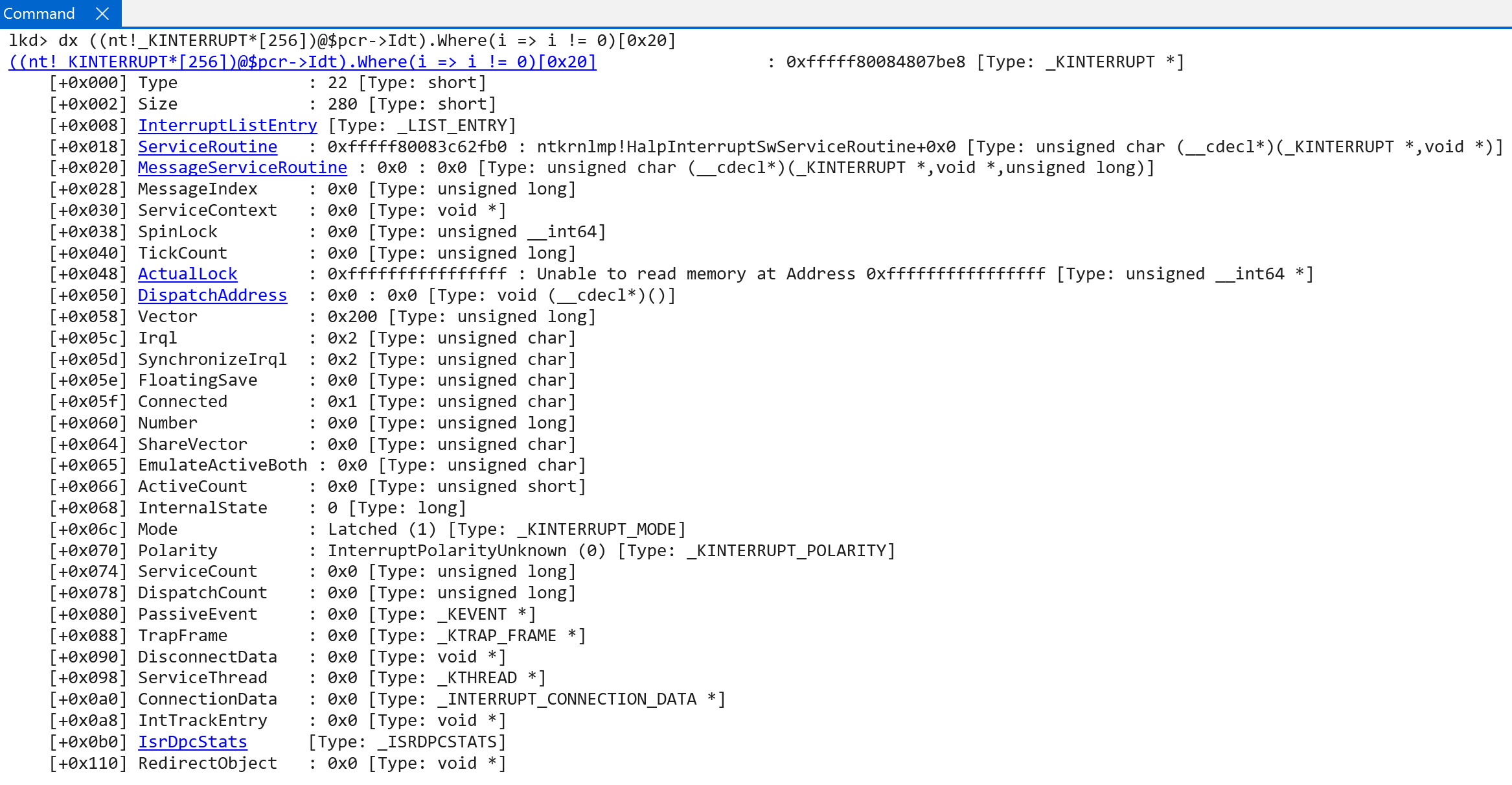

After the controller is registered, it has still not been initialized completely. First, the GIC version is preserved (nt!HalpInterruptGicVersion). Next, before each of the interrupt controllers (in our case, just one) is actually fully-initialized, many of the crucial and low-level interrupt handlers, like the CPU’s SGI (e.g., inter-processor interrupt, via KiIpiServiceRoutine), the reboot service (nt!HalpInterruptRebootService), etc. are registered via nt!HalpCreateInterrupt. nt!HalpCreateInterrupt is responsible for allocating an interrupt object (nt!_KINTERRUPT) - which represents a particular type of interrupt and allows the OS/software to register a particular interrupt service routine (KINTERRUPT->ServiceRoutine). nt!KeInitializeInterruptEx is responsible for filling out the majority of the nt!_KINTERRUPT object, including passing parameters from nt!HalpCreateInterrupt - such as the ServiceRoutine, Vector (more on this in a little bit, but there is a maximum value of 0xFFF), and Irql (IRQL the CPU will be when the interrupt occurs).

After the various interrupt objects (we still have not called nt!HalpInterruptInitializeController) are created they are then connected to the IDT via nt!KiConnectInterruptInternal.

The first thing that nt!KiConnectInterruptInternal (on Windows on ARM) does is perform some basic validation. The target interrupt to connect cannot have a vector number greater than 4095 (more on this later), the IRQL associated with the target interrupt cannot be higher than HIGH_LEVEL, ensure the Number member of the KINTERRUPT object is valid (this is not the interrupt number, but is instead the target CPU number for which the interrupt has been initialized for), and ensure that the SynchronizationIrql associated with the interrupt object (the IRQL at which the lock stored in the interrupt object itself is acquired) is valid.

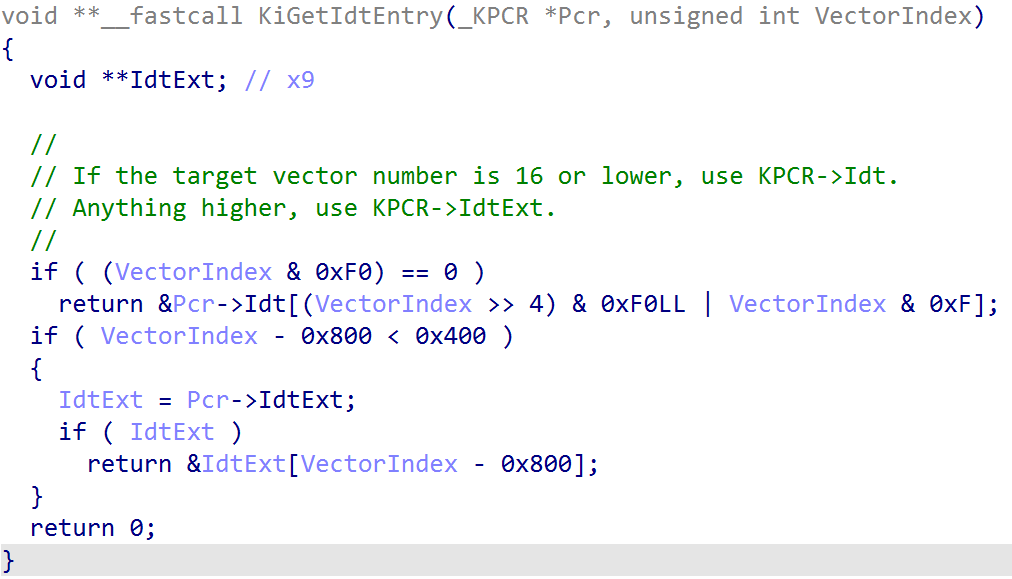

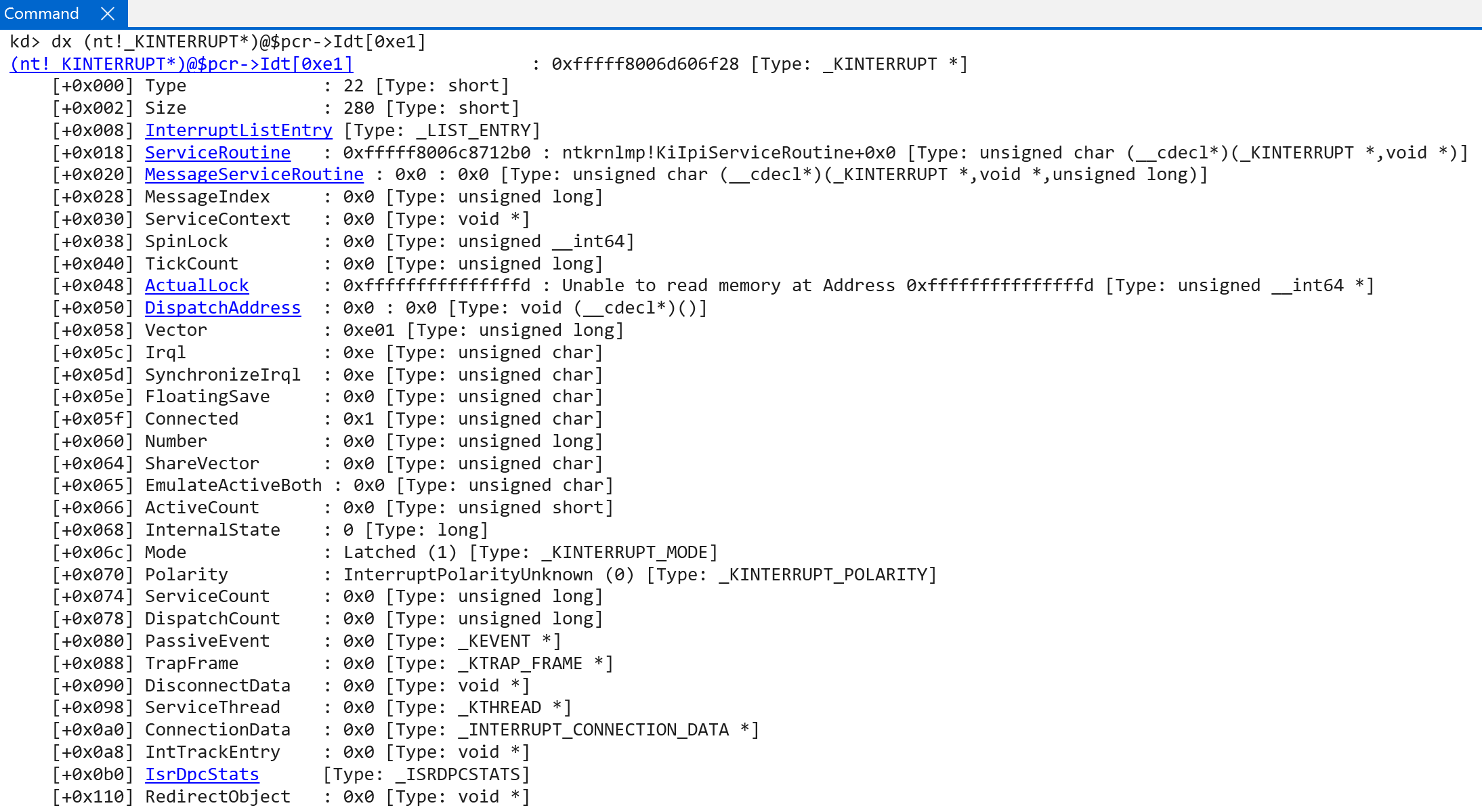

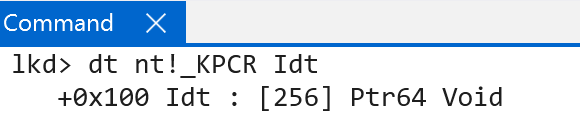

After basic validation, the kernel will index the per-CPU IDT via KPCR->Idt (via nt!KiGetIdtEntry) to locate the target location where the interrupt object we want to connect to the IDT will reside (notice we do not use KPCR->IdtBase, which is the related field on x64. This field does not exist on ARM64). This will store the first 16 interrupts which are registered. Anything over the first 16 will be stored in the extended IDT (KPCR->IdtExt).

For example, the SGI/IPI interrupt is registered through a call to nt!HalpCreateInterrupt with the following parameters:

HalpCreateInterrupt(KiIpiServiceRoutine,

0xE01,

0xE);

0xE01 represents the KINTERRUPT.Vector interrupt object value. This can be seen below.

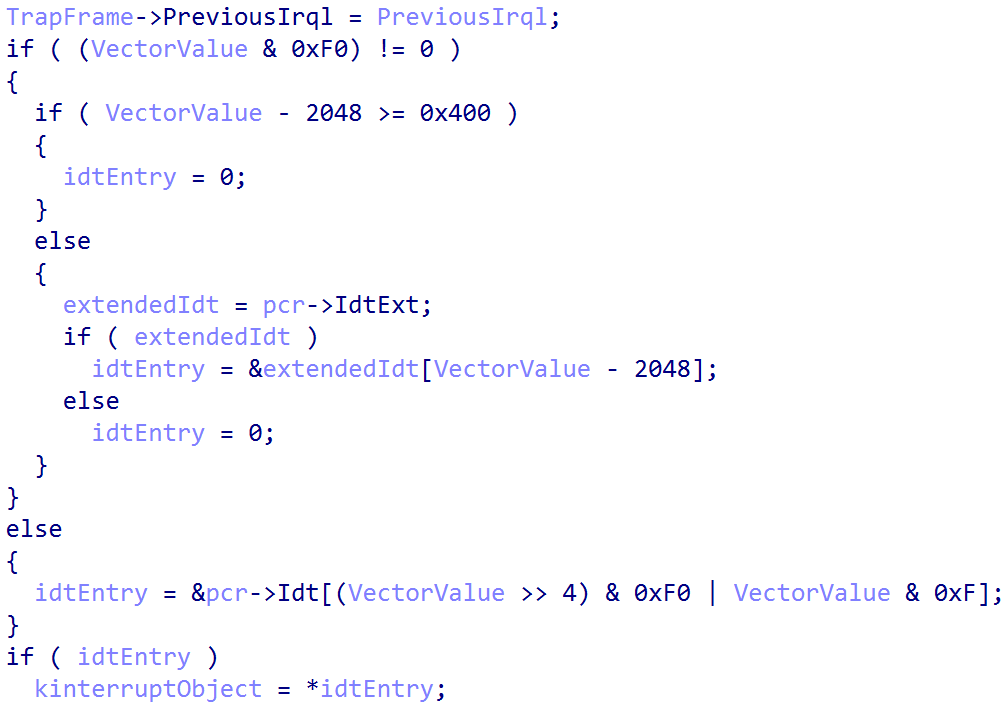

This means that in our case nt!KiGetIdtEntry would index the first “regular” IDT (KPCR->Idt), because the lower nibble is less than the maximum value of 16. There is some difference, however, with how a particular IDT entry is accessed between x64 and ARM64 (the CPU does not know about the IDT layout via the IDTR, for example, since a generic interrupt controller is being used). We will talk more on this in the section on interrupt dispatching and handling. In addition, although the variable here is named VectorIndex this is not entirely true. This value contains more than just a vector index. This can be seen by how this value is accessed in software:

- Extracting the upper byte of

KINTERRUPT.Vector(0xE0) - Adding the lower nibble to the remaining value.

In our example, 0xE01 becomes 0xE1. This is the index into the IDT for the target interrupt. This is where, into the IDT, the actual interrupt object is written.

As a side note, the value of the vector seems to be a effectively a masking of the target IRQL for the interrupt and the actual index into the IDT. So 0xE01 has an IRQL of 0xE, etc. - with one exception, which I am unsure of why at the current moment - and that is the interrupt associated with rebooting. For an unknown reason this interrupt object (nt!HalpInterruptRebootService) has a vector of 0xd07 and an actual IRQL of 0x7.

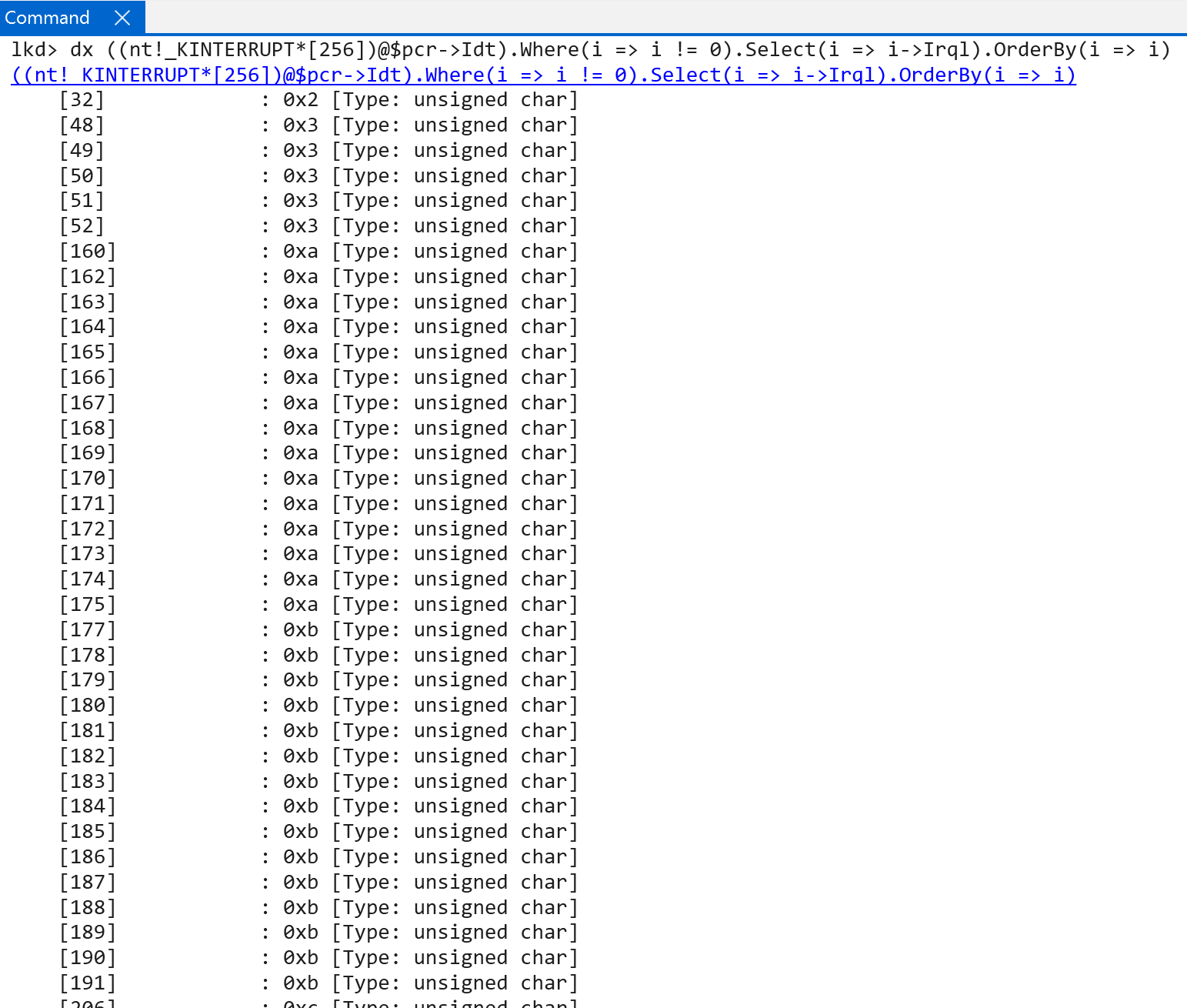

It would seem that there can be, in this case, 16 IRQLs (as there is on Windows on ARM) and each of these IRQLs can have 16 associated interrupts - for a total of 256 interrupts. This makes sense, as technically the IDT array in the processor control region (nt!_KPCR) is technically a hardcoded 256-element array!

As an aside, on my current ARM machine, the “lowest” IRQL with a registered interrupt is that of 0x2, or DISPATCH_LEVEL. The service routine for this interrupt is nt!HalpInterruptSwServiceRoutine - which seems to indicate this is the software interrupt service routine (which is a wrapper to the real function, nt!KiSwInterruptDispatch - which is famous for being associated with PatchGuard and is also present in the x64 IDT. It does not seem to be an actual interrupt handler, but more present as a “security-by-obscurity” feature).

Once the initial interrupt objects have been connected to the software-representation of the interrupt controller (nt!HalpRegisteredInterruptControllers) a call to nt!HalpInterruptInitializeController occurs - which performs much of the lower-level interrupt initialization logic. This effectively begins by forwarding the in-scope registered interrupt controller to nt!HalpInterruptInitializeLocalUnit.

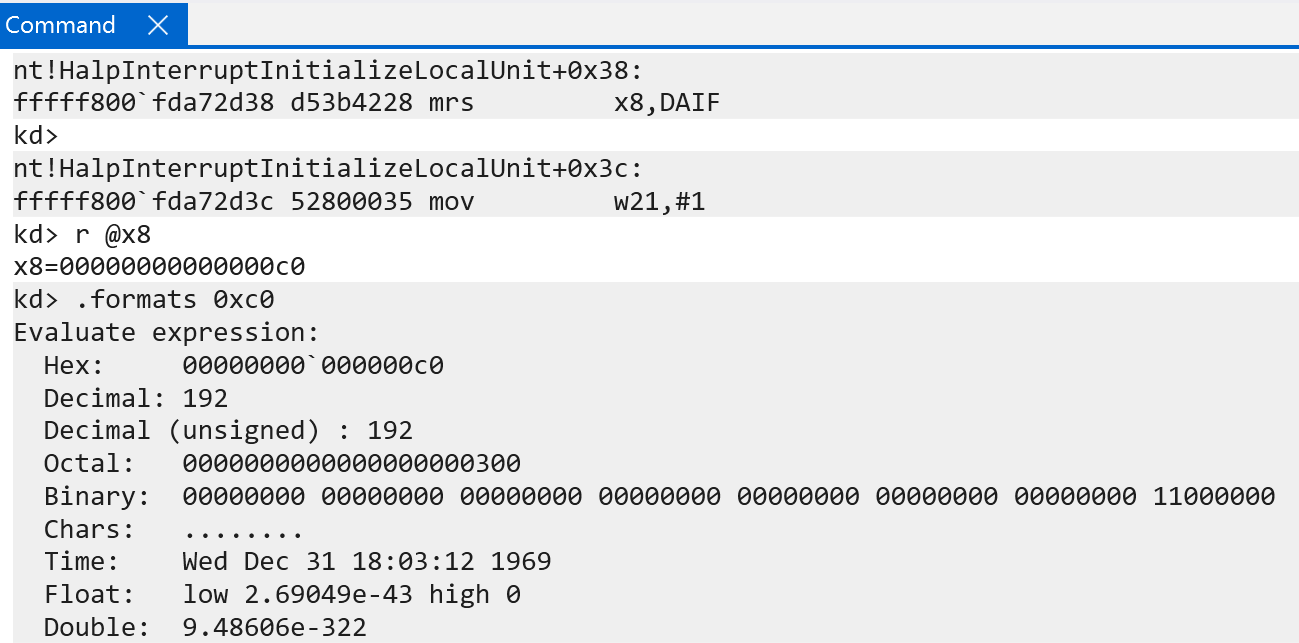

nt!HalpInterruptInitializeLocalUnit begins by checking if the DAIF system register has DAIF.I set - which indicates the status of whether or not IRQ exceptions are masked. This is another way of checking if interrupts will be received by the current exception level. On my current machine, at this stage in the system initialization, both FIQs and IRQs are masked. If, for whatever reason, IRQs and FIQs were not masked (effectively “temporarily disabled”) this function would set DAIFSet to a mask of 0b11 - which allows writing to the DAIF system register.

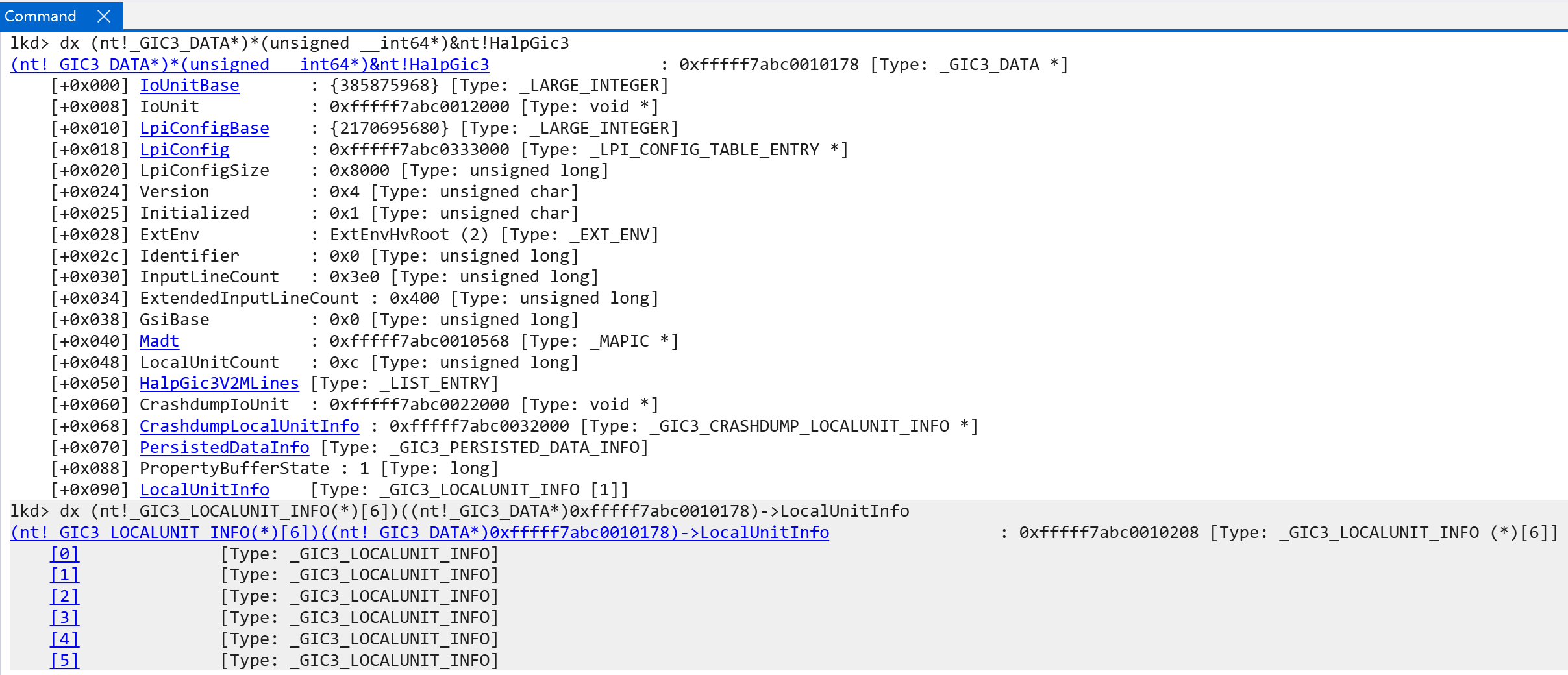

After interrupts are temporarily disabled, nt!HalpInterruptInitializeLocalUnit will invoke nt!HalpGic3InitializeLocalUnit. nt!HalpGic3InitializeLocalUnit is one of the registered functions with the registered interrupt controller (REGISTERED_INTERRUPT_CONTROLLER.FunctionTable[InitializeLocalUnit]). nt!HalpGic3InitializeLocalUnit accepts an argument to the registered controllers internal data (REGISTERED_INTERRUPT_CONTROLLER.InternalData). The internal data is filled out in nt!HalpGic3RegisterIoUnit and, after construction, the internal data is stored in the global variable nt!HalpGic3. This internal data is accessible as a GIC3_DATA structure - which is in the symbols. The internal data uses an ANYSIZE_ARRAY pattern to also store N-number of GIC3_LOCALUNIT_INFO structures after the internal internal data itself - with N referring to the amount of CPUs on the current machine.

Some items of interest worth calling out in the GIC3_DATA structure, which provide an additional layer of abstraction. Most other data is pretty self-explanatory:

IoUnitBase= the physical address of the GIC DistributorIoUnit- the mapped virtual address of the GIC DistributorGsiBase- From the ACPI spec - this is the Global System Interrupt (GSI) base value. Effectively the base number of the wired interrupt numbers available. 1:1 mapping to AMR’s INTIDsIdentifier- the GIC Distributor’s hardware ID

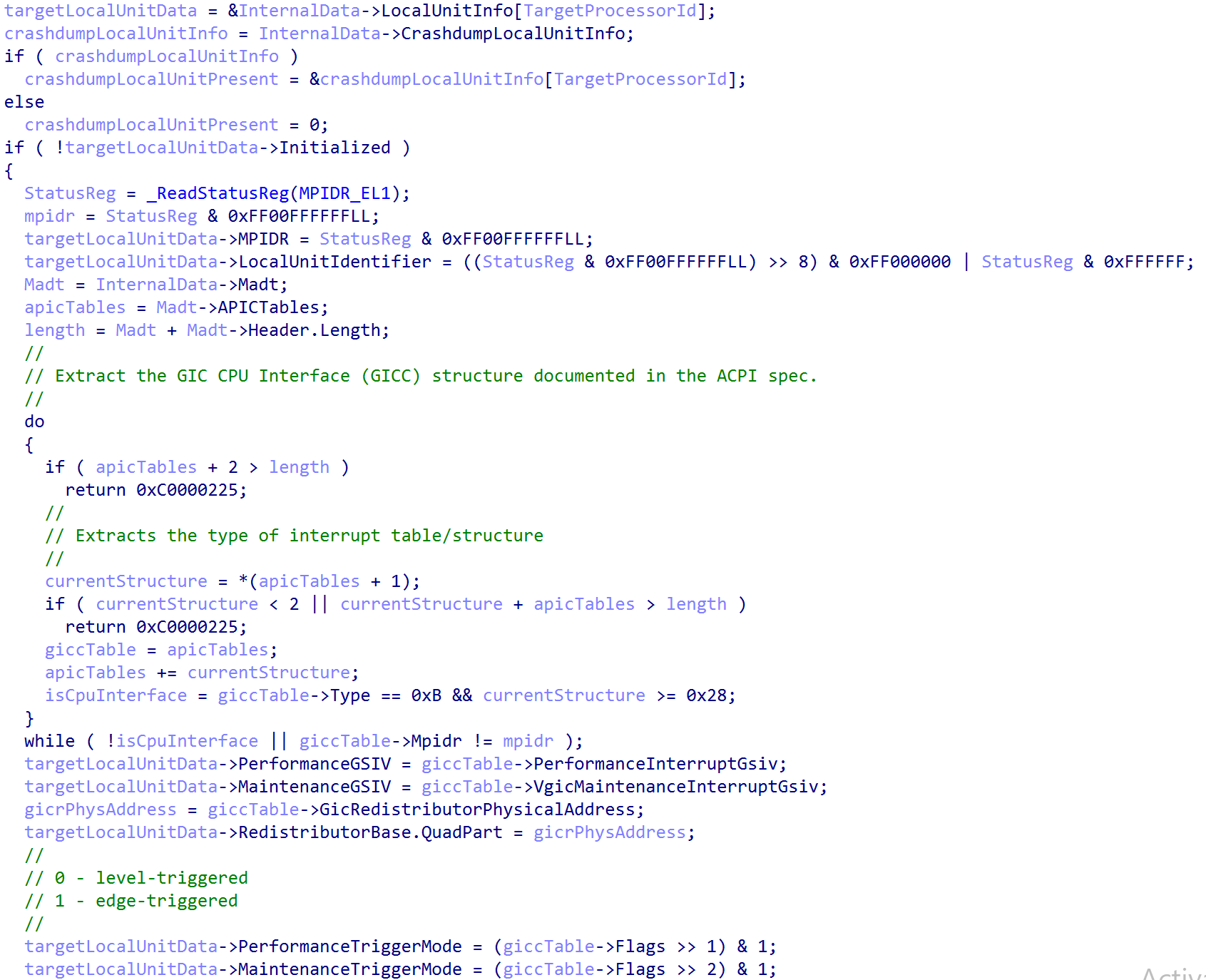

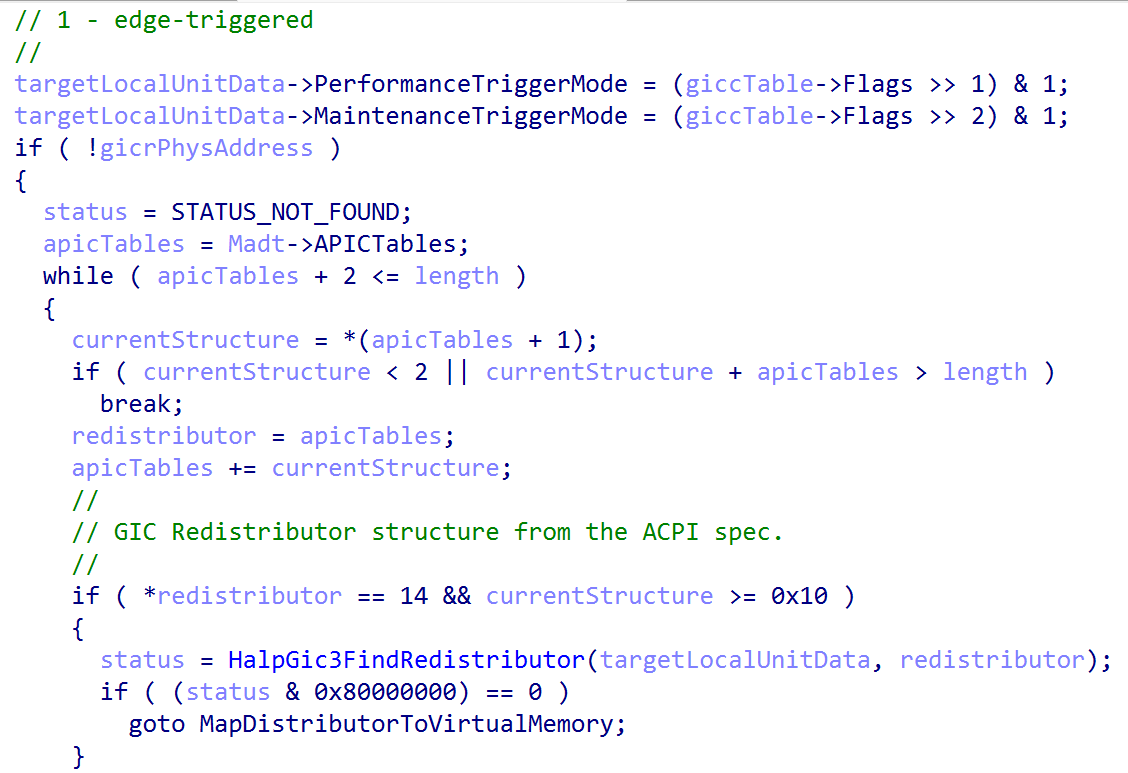

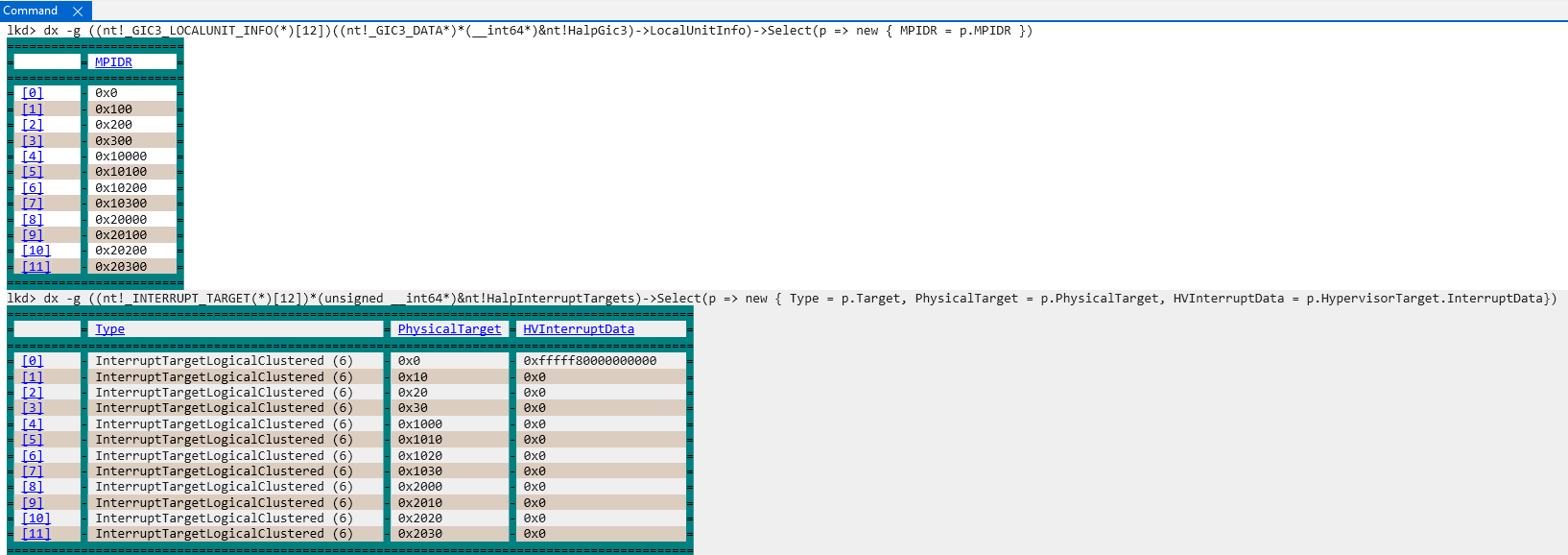

nt!Halp3Gic3InitializeLocalUnit begins by locating the target CPU’s local unit info - represented by the _GIC3_LOCALUNIT_INFO structure, as previously mentioned. If the local CPU interface has not been initialized, it is then configured. The local unit is the representation of the local CPU’s interrupt schema - including redistributor and CPU interface information. The ACPI’s interrupt table is parsed for the redistributor and CPU interface structures. From these structure the physical address of the redistributor is mapped into virtual memory, various trigger modes are extracted (performance and maintenance interrupts are denoted as either level-sensitive or edge-sensitive. Edge-sensitive means an interrupt is only “received” when there is an actual change in the physical interrupt line (e.g., 0 -> 1, such as voltage goes down from up or up from down). Level-sensitive means that an interrupt is received/reported when the interrupt line is asserted (the line is “set to 1” if we are over-simplifying) regardless of if this was a change from the previous state). Additionally, the MPIDR_EL1 system register, the Multiprocessor Affinity Register, is preserved - which is the register that contains identifying information about a target processor (effectively a unique processor identifier, with much more granular information like cluster ID in a cluster of processors - which are a grouping of processors used to share resources/etc.). In this case all of the “non-identifier” bits (bits in the register that denote metadata, usch as indication of a uniprocessor system) are cleared and the affinity bits are used to identify the CPU (affinity level 0, 1, 2, 3)

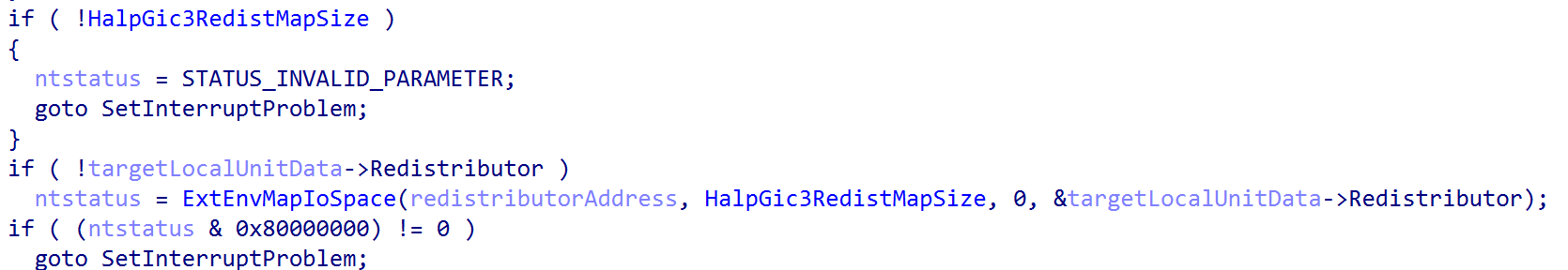

Finally, the redistributor is mapped into virtual memory (with the size of the mapping being represented by HalpGic3RedistMapSize, which is computed in nt!HalpGic3RegisterIoUnit). This marks the local unit as initialized (GIC3_LOCALUNIT_INFO->Initialized = 1).

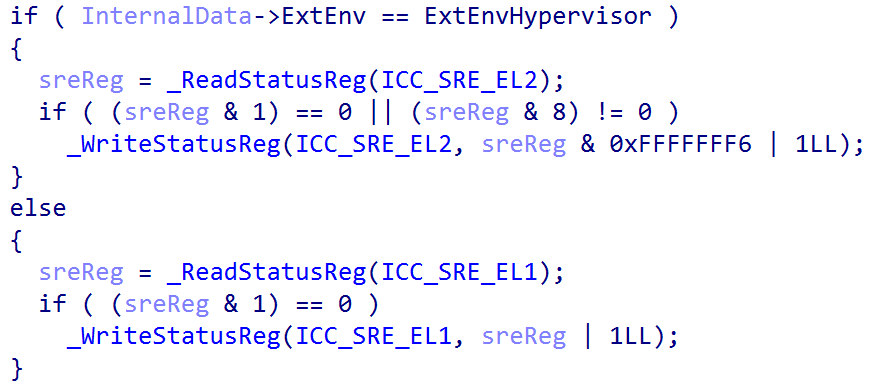

Next, the appropriate Interrupt Controller System Register Enable, or ICC_SRE_ELX register is read. It is worth calling out some nuance here. ICC_XXX actually replaces GICC_XXX in our case. GICC_XXX refers to legacy registers. In GICv3, according to the documentation, the physical CPU interface registers are prefixed with ICC and the virtual CPU interface registers are prefixed with ICV instead of GICV. This is why in Windows, for example, you will only see writes to the ICC_XXX system registers.

The kernel will always set bit 1, if it is not already set. This is the ICC_SRE_ELX.SRE bit - which denotes if the memory-mapped interface or system register interface should be used to interface with the GIC CPU interface for the target CPU. By setting the value to 1, this indicates that the system register interface will be used (as the GIC documentation also states that system registers must be used when affinity routing is in-use for all enabled security states. It is worth calling out some items, like the GIC distributor, are always memory-mapped).

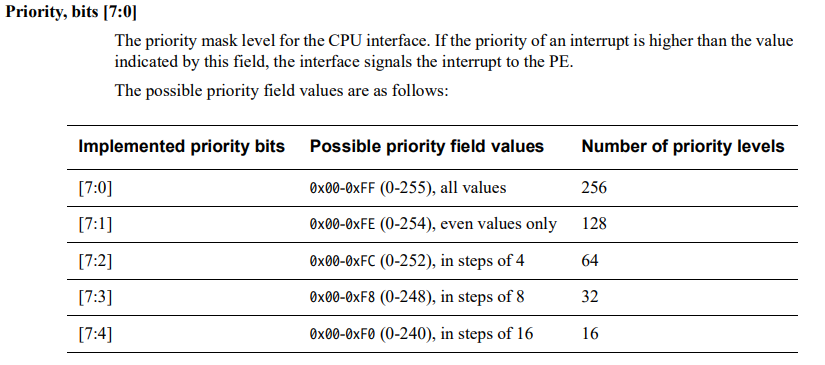

The kernel then disables group 1 interrupts for the time being (there are only 2 groups, group 0 is for interrupts handled EL3, so group 1 is for all other interrupts in the current exception and security level. Remember that Windows does not use the traditional security levels, as it already uses VTLs to separate “secure and non-secure worlds”), sets the interrupt priority filter to 0 (meaning the CPU will accept interrupts with a priority higher than 0. 0 is the highest value, so this effectively means only the interrupts higher than a priority of 0 can be let through. Given that 0 is the highest priority, as the lower the number the higher the priority, this also helps to disable interrupts until the local unit is configured), and also sets the interrupt controller binary point register for EL1 to a value of 3 - which is the minimum value needed.

At this point it is probably worth briefly mentioning interrupt grouping. Interrupt grouping allows the GIC to group interrupts based on a set of characteristics - specifically aligned to the ARM security and exception model. Interrupt grouping groups interrupts by security state (non-secure and secure worlds) and exception level. It is also worth calling out that Windows only uses group 1 interrupts and specifically only in the non-secure state. This can be confirmed by reading the GICD_CTLR.EnableGrpXXX values from the GIC distributor - which describes what groups of interrupts are enabled. This can also be further confirmed by parsing ntoskrnl.exe and hvaa64.exe (Hyper-V) for a lack of writes to the system regiseters ICC_IAR0_EL1, ICC_EOIR0_EL, etc. where 0 refers to group 0 - which are the interrupts associated with interrupts being handled at EL3, which is the “bridge” between non-secure and secure worlds.

GICD_CTLR.EnableGrp0= 0GICD_CTLR.EnableGrp1NS= 1 (Non-Secure)GICD_CTLR.EnableGrp1S= 0 (Secure)

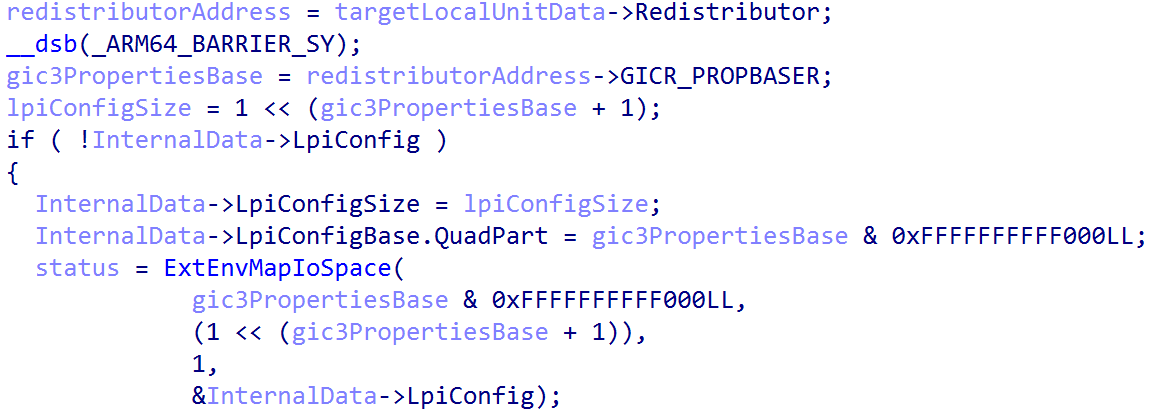

Moving on, nt!HalpGic3InitializeLocalUnit then proceeds to fill out some additional GIC redistributor information in the GIC3_LOCALUNIT_INFO structure. First, information of interest from the LPI configuration table, which is tracked by the in-scope CPU’s GIC redstributor, is added to the “internal data” we have been examining so far (tracked via nt!HalpGic3). This is achieved by accessing the GICR_PROPBASER register from the GIC redistributor - which specifies the LPI configuration table.

The LpiConfig member of the GIC3_DATA structure, of type LPI_CONFIG_TABLE_ENTRY, maintains the virtual address of target CPU’s LPI table (and all other LPI configuration tables). Note that the redistributor’s format is documented by ARM, and is not part of the Windows symbols.

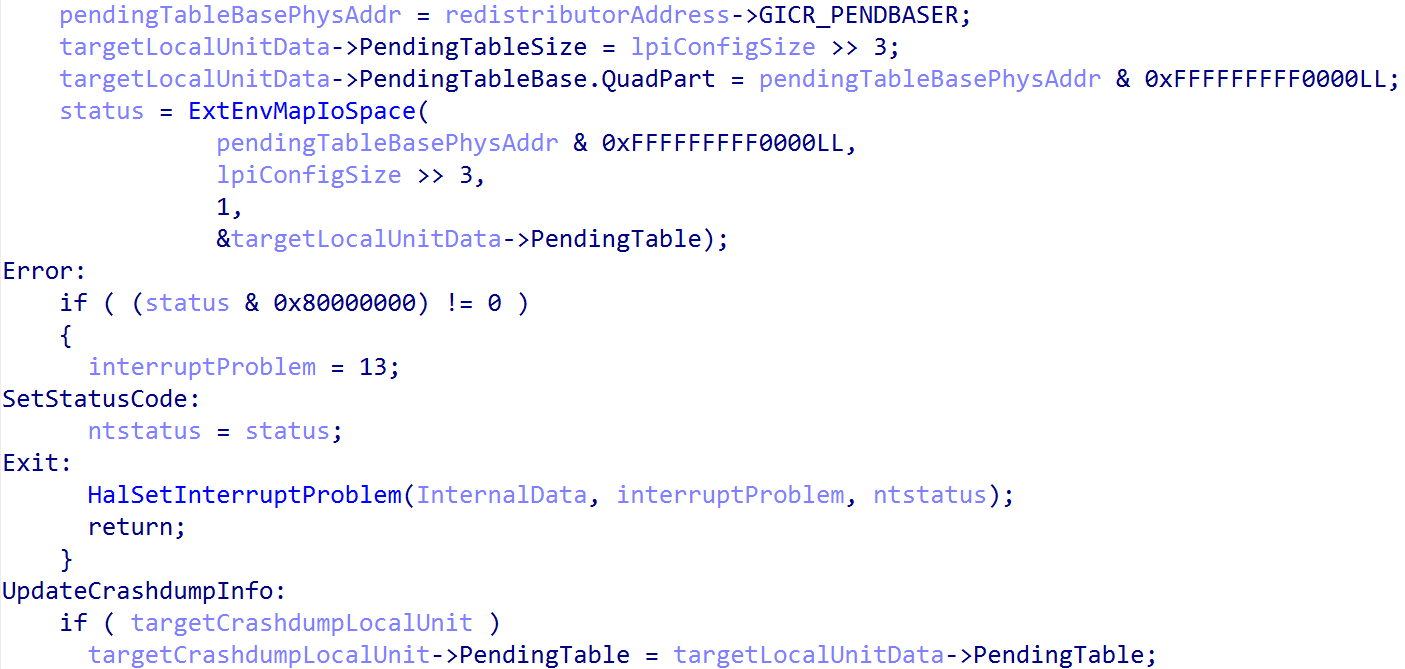

Next the LPI pending table is mapped into virtual memory and this time is tracked this time through the local unit’s structure (GIC3_LOCALUNIT_INFO) as the PendingTable member. This is achieved by accessing the GICR_PENDBASER register from the GIC redistributor’s memory-mapped interface. In addition, the global GIC data structure (nt!HalpGic3) that represents, in virtual memory, the state of the GIC updates the per-CPU crash dump information. The pending LPI table is also added to the crash dump information.

One thing to call out - it should be noted that starting at an offset of 0x10000 (64KB) after the GIC redistributor registers (which contains GICR_CTLR, etc.) comes the GIC redistributor registers responsible for configuring SGIs and PPIs. They are also documented by ARM. This is also called out in the GIC documentation:

Each Redistributor defines two 64KB frames in the physical address map:

- RD_base for controlling the overall behavior of the Redistributor, for controlling LPIs, and for generating LPIs in a system that does not include at least one ITS.

- SGI_base for controlling and generating PPIs and SGIs.

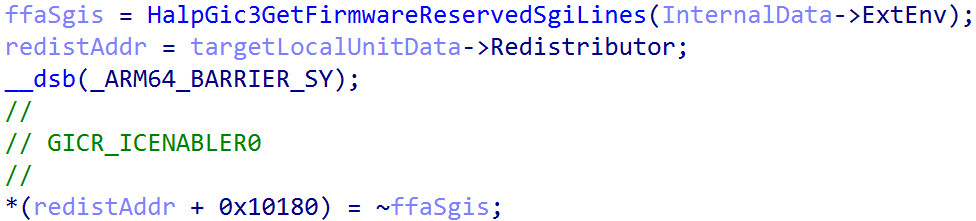

This means that from GIC3_LOCALUNIT_INFO->Redistributor + 0x1000 contains the start of the SGI/PPI redistributor registers. From the SGI/PPI registers the GICR_ICENABLER0 register, or the Interrupt Clear-Enable Register 0 register, is configured. This register is configured to enable the forwarding of all interrupts to the GIC redistributor by setting the enable bit (indicated by writing a value of 1) to the target register - while also being sensitive to any SGIs (GICR_ICENABLER0 encapsulates both SGIs and PPIs) which are reserved for the ARM Firmware Framework A-Architecture (FF-A). Specifically, the FFA_FEATURE call is made to retrieve the interrupt ID (INTID) for the Schedule Receiver interrupt (SRI) and ensures that this interrupt ID is always disabled. However, this is only applicable in some operating environments (like without the presence of Hyper-V) and, therefore, my machine shows that nt!HalpFfaEarlyErrorRecords, an array of errors associated with initializing FF-A, reports an error of STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED, which is translated from the FFA_ERROR code of NOT_SUPPORTED (and, thus, no need to worry about “special” handling of SGIs associated with the FF-A). This means that there is no SGI reserved for the FF-A’s SRI. This is just something I felt the need to call out. This can be also further validated by checking the presence of nt!HalFfaSupported and nt!HalFfaInitialized - which denote FFA support and state.

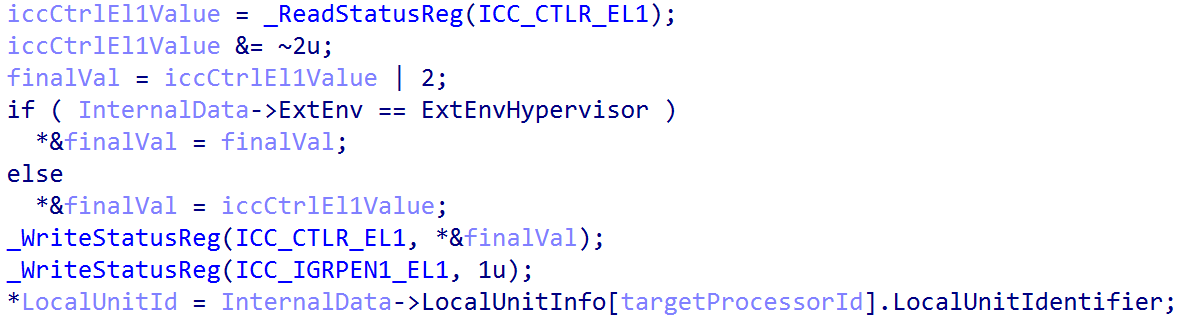

Finally, one of the last nt!HalpGic3InitializeLocalUnit does is configure the ICC_CTLR_EL1 system register, which is the Interrupt Control Register. If the operating environment is ExtEnvHypervisor then ICC_CTLR_EL1.EOIMode (End-of-interrupt) is set. Otherwise (as is in our case, since our operating environment is ExtEnvHvRoot) EOIMode is set to 0. End of interrupt (EOI) refers to a specific action that is taken to indicate that the software routine which handled a target interrupt has completed. A value of 0 in the register indicates that a write to, for example, ICC_EOIR1_EL1 (which is for group 1 interrupts) is both responsible for “priority drop” and deactivation of an interrupt. Whereas a value of 1 indicates a write to a separate register is needed for deactivation. The [ARM] documentation on configuring the GIC states that this mode (EOIMode == 1) is used for virtualization purposes.

nt!HalpGic3InitializeLocalUnitData ends by re-enabling interrupts, now that the local CPU unit (redistributor and CPU interface) is configured, via ICC_IGRPEN1_EL1 (and later nt!HalpInterruptMarkProcessorStarted marks the processor as “started” for interrupts)

After nt!HalpGic3InitializeLocalUnit data exits, a per-CPU (technically per-core, and my system has 12 cores) structure, INTERRUPT_TARGET, is filled out and managed by the symbol nt!HalpInterruptTargets. This is achieved via nt!HalpGic3ConvertId. These structures outline additional information about the CPU schema, such as if the CPU resides in a cluster, along with CPU ID information. The CPU ID information is effectively the previously mentioned affinity values from the MPIDR_EL1 system register.

After configuring the interrupt targets (representing the targets for which interrupts can arrive) the real per-CPU interrupt priority is set with a call to nt!HalpGic3SetPriority (we saw earlier it was temporarily set to 0). After the local unit is stood up, the priority is updated per-CPU to 0xF0. 0xF0 is 0b11110000 in binary (and bits 0:7 in ICC_PMR_EL1, the priority register, make up the priority level). When setting a value of 0xF0 this indicates that the total number of priority levels is 16. This means priority levels 0 - 15 will be handled by each CPU interface.

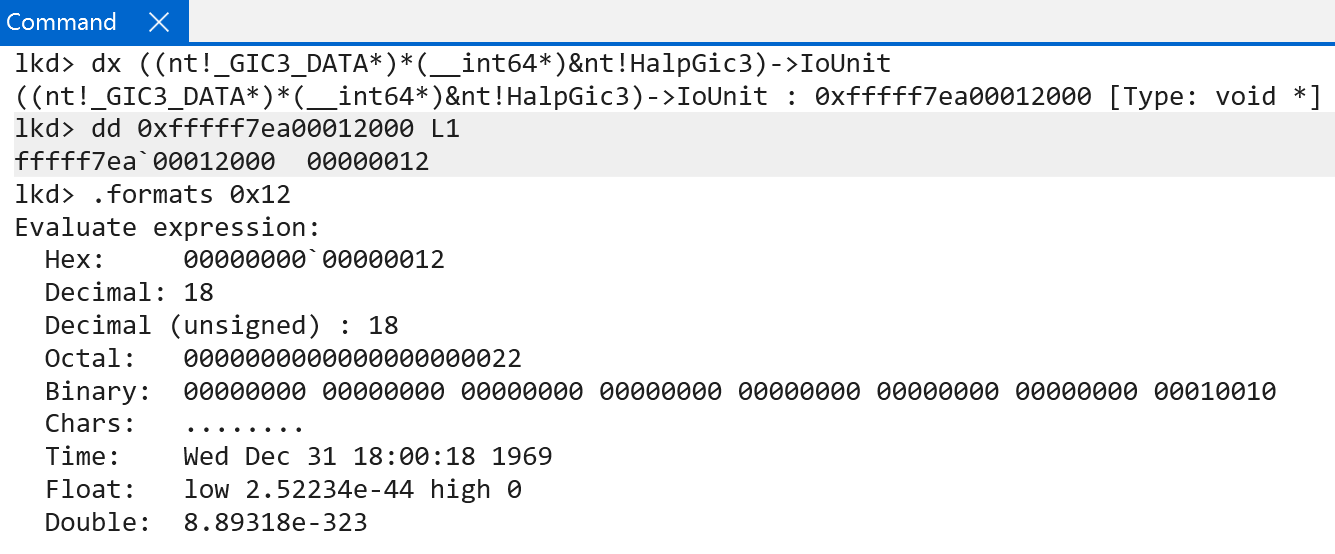

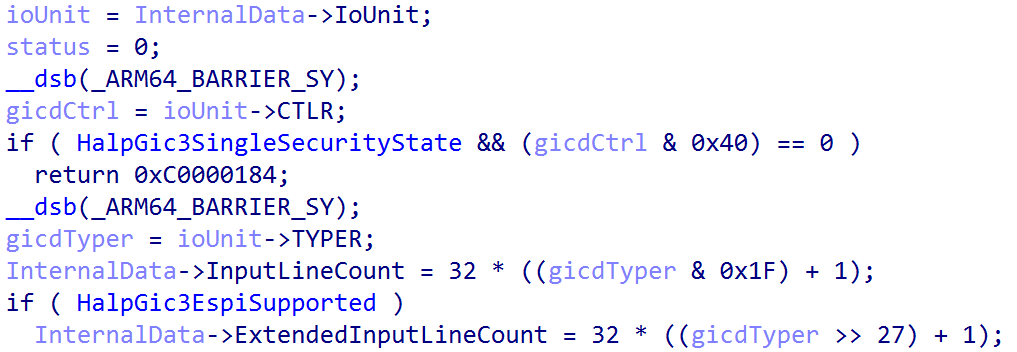

Once the priority level has been configured (for each CPU), execution is transferred to the function nt!HalpGic3InitializeIoUnit - which accepts a parameter to the GIC3_DATA we have been referencing - is called. Specifically the GIC3_DATA->IoUnit is configured - which is GIC distributor structure’s virtual address. This means this function is not called per-CPU and instead is called to perform further configuration of the singular GIC distributor. When I say “GIC distributor structure” I am referring to the ARM-documented “one” with all of the memory-mapped registers like the GICD_CTLR, GICD_TYPER, etc. This is where more configuration of these registers occurs.

GIC3_DATA->InputLineCount is first configured. This is done by extracting GICR_TYPER->ITLinesNumber. According to ARM documentation, the ITLinesNumber is the “number of SPIs divided by 32”. So, InputLineCount is simply GICR_TYPER->ITLinesNumber * 32. This refers, effectively, to the maximum SPI INTID. This calculation also has to do with the number of interrupt lines (lines = interrupt IDs in our case) that are even available - although some interrupt sources may share a line.

We already previously talked about extended SPI support. This is indicated by GICD_TYPER->ESPI. The machine this analysis was conducted on has extended SPI support. When extended SPI support is enabled, bits 31:27 in the GICD_TYPER are no longer “reserved” - but refer to ESPI_range. This is extracted and stored in ExtendedInputLineCount to indicate the maximum supported extended SPI INTID.

From here Windows then unconditionally clears GICD_CTLR.EnableGrp1NS - which is represented by bit 1 (from index of 0). This means this disables interrupts in the non-secure group 1 group. This is a temporary measure while the rest of the GIC distributor is configured. Next, if the GIC distributor (which, again, is memory-mapped in physical memory and has not been yet fully-configured by the operating system) has GICD_CTLR.ARE_S configured - which enables affinity routing in the secure state - or if ARE_S is not set (which in this case ARE_S is set to 1 - meaning either way ARE_S is going to be set to 1) the interrupt lines which are supported go under further configuration.

The GICD_ICENABLER<n> register, part of the distributor, contains a bitmask which corresponds to a particular interrupt that denotes if forwarding of the interrupt from the distributor to the target CPU interface is allowed. nt!HalpGic3InitializeIoUnit beings by configuring all of the GICD_ICENABLER registers (which are 4 bytes each) to a value of 0xFFFFFFFF - which prevents any interrupts from being forwarded to the target CPU interface.

Next, all of the GICD_IROUTER<n> registers (and all of the GICD_IROUTER<n>E, for extended interrupts) for the GIC distributor (still being configured) are all set to a value of 0. A GICD_IROUTER register, which is 8 bytes, contains the necessary information for routing a particular SPI (SPI, not SGI, etc.) for a particular interrupt number.

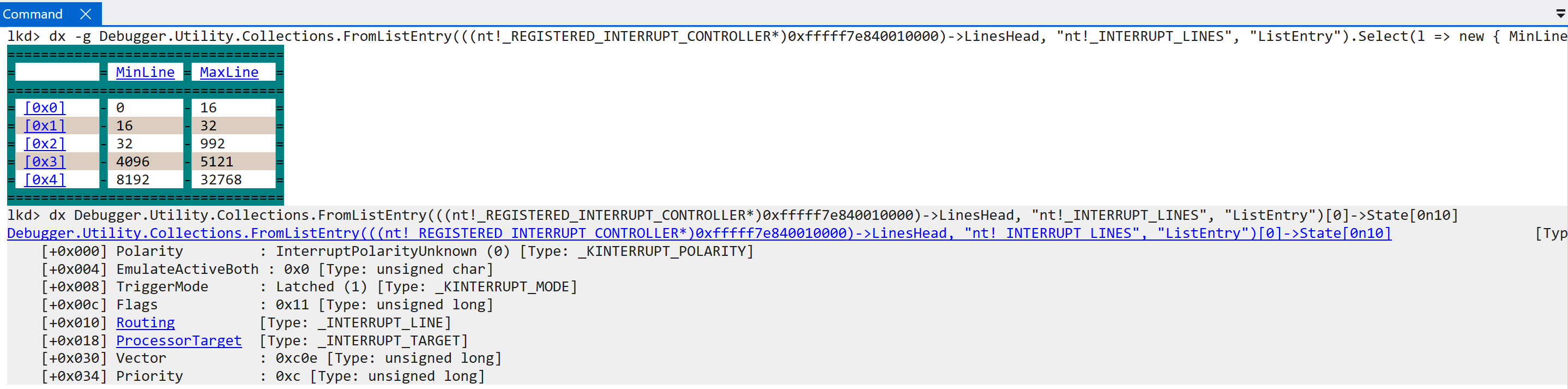

Lastly for this function, if the local unit data has not been marked as initialized, a call to nt!HalpGic3DescribeLines occurs. This results in the filling out of INTERRUPT_LINES structures, which are maintained in a doubly-linked list, which define the type of interrupt line (we have already talked about “lines”, but the lines on which an interrupt arrive are associated with a particular interrupt source like an SGI, PPI, etc.), internal line state, etc. All of the interrupt lines are maintained through the registered interrupt controller through the LinesHead linked list head.

As we can see, the “max” and “min” line values refer to the values in which an interrupt ID resides (this refers to the “lines” on which interrupts can arrive - an interrupt is tied to an ID). For example, the interrupt line described as InterruptLineMsi, which refers to message-based interrupts, can have an interrupt ID from 8192 - 32768 - this is outlined as well by ARM documentation. The INTERRUPT_LINES list maintains information about each of the interrupt sources and all of the lines on which an interrupt can arrive (there is a difference between what is possible and what is supported. Windows does not support handling every single interrupt ID). The initialization of all of the interrupt lines results then in the GIC3_DATA (nt!HalpGic3) being fully initialized (InternalData->Initialized = 1) and also re-enabling group 1 non-secure interrupts (GICD_CTLR.EnableGrp1NS), which was previously cleared. This completes, finally, the functionality encapsulated by nt!HalpInterruptInitializeController.

If interrupt initialization has been succcessful up until this point, a call is made to parse the entire MADT (Multiple APIC Description Table, which we have already talked about) via nt!HalpInterruptParseMadt. Technically speaking this occurs as a result of another call to nt!HalpInterruptParseAcpiTables. We previously saw this function was one of the first invoked in the nt!HalpInitializeInterrupts routine - which kicked off the interrupt initialization. However, a boolean gates whether or not the MADT is actually parsed (which denotes if an interrupt controller has been registered yet). This second call now passes in “true” and, thus, we parse the MADT.

nt!HalpInterruptPraseMadt determines which features are available for the interrupt controller - such as the layout of the GIC distributor, redistributors, etc. This is particularly interesting, because comparing the code between x64 and ARM - there is effectively 100% overlap. For instance, ARM machines employ a GIC - but yet there is code which validates APICs. For x64, there is code which validates GICs. As far as our ARM analysis goes, the parsing is done to gather additional information about the specifics of the interrupt controller implementation (GIC) for determining if, for example, interrupts need to be “hyper threading aware” (nt!HalpInterruptHyperThreading), a list of non-maskable interrupt sources (NMI), etc.

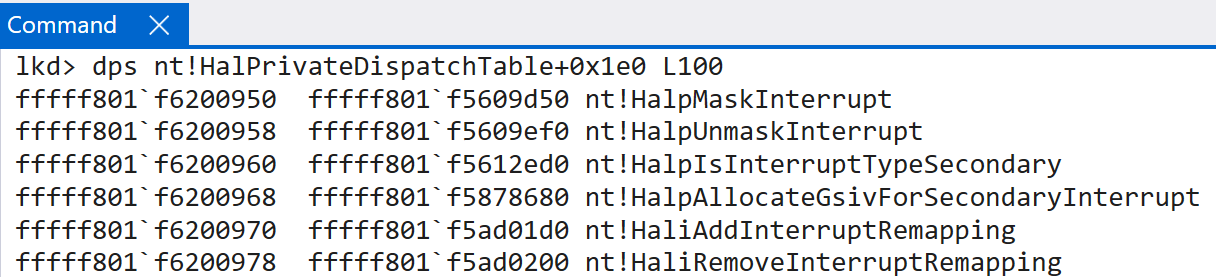

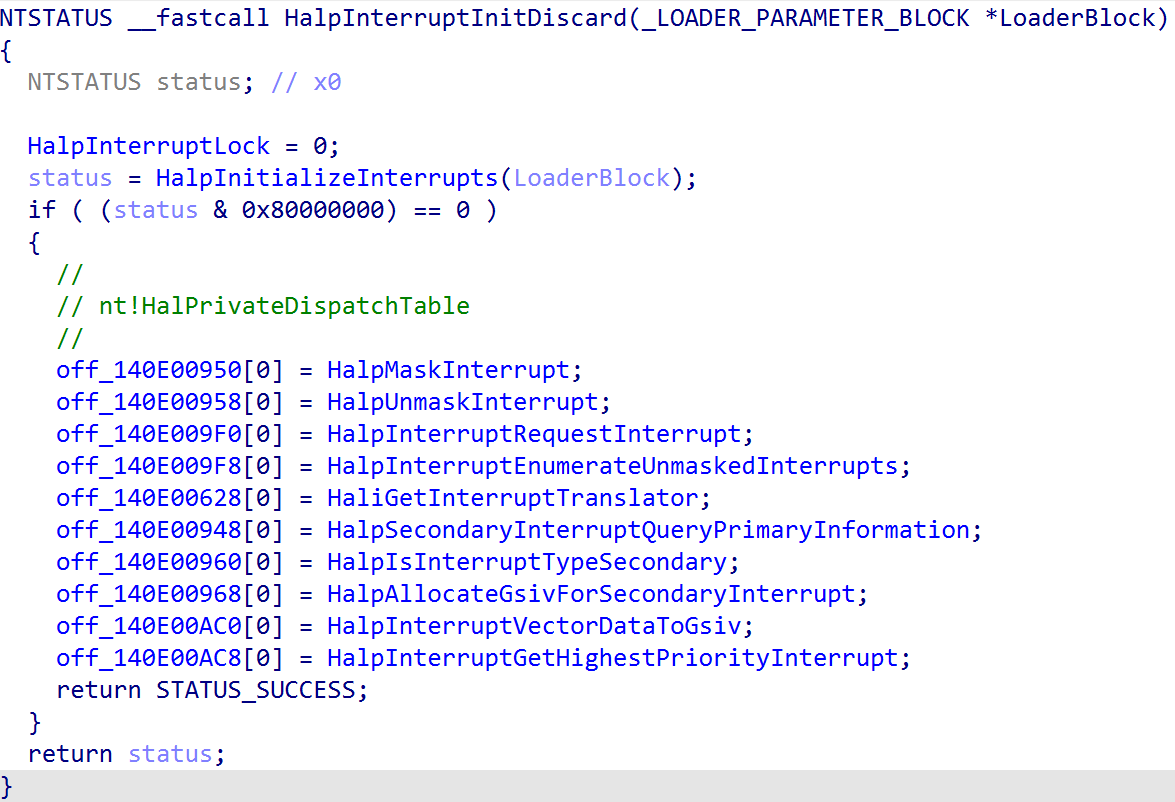

Finally, the last part of the interrupt initialization results in the initialization of the IPIs (which are a common name for SGIs. These are the inter-processor interrupts where cores can send interrupts to other cores) via nt!InterruptInitializeIpis. Once this has completed, the HAL’s private dispatch table is updated (nt!HalPrivateDispatchTable) with a few interrupt-relevant routines.

Interrupt Delivery and Handling - Windows on ARM

With the interrupt controller now configured and initialized the OS can now start receiving interrupts in software. As previously mentioned in another blog - even interrupts are delivered as “exceptions” on ARM.

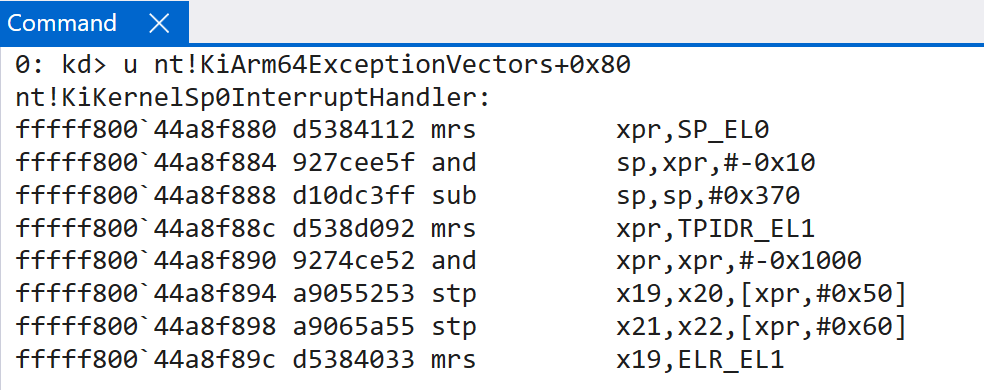

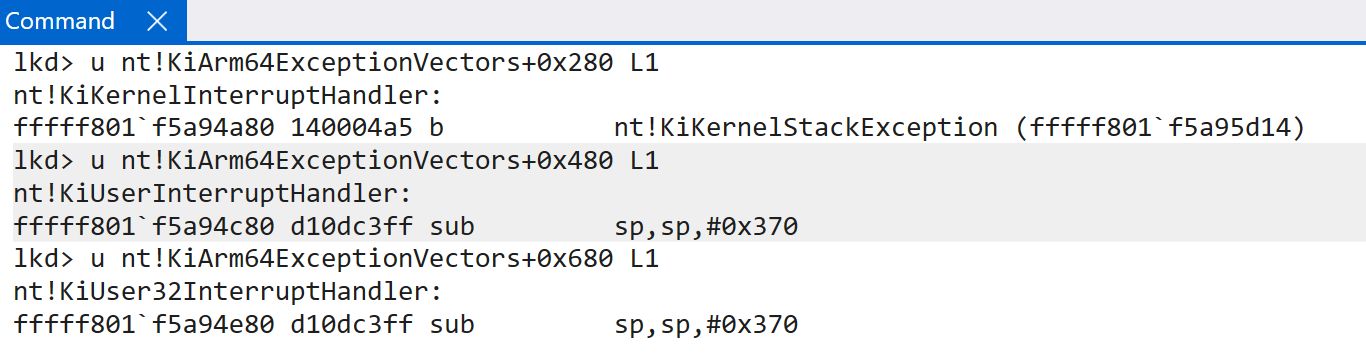

This obviously means one of the main differences between x64 and and ARM is how interrupts arrive in software, and then even further how the high-level handler invokes the interrupt-sepcific handler (for example, there is no IDT on ARM and there is no nt!KiIsrThunk or nt!KiIsrLinkage). Interrupts are dispatched as exceptions (typically an asynchronus exception which mean the exception is external to the CPU) - and thus, it is worth quickly examining the details surrounding how exception dispatching reaches the high-level interrupt handler on ARM64 Windows systems. Windows ARM systems maintain a vector of exception handlers through the symbol nt!KiArm64ExceptionVectors (and, for EL1 - kernel-mode - this is stored in the VBAR_EL1 system register). This is not an array of function pointers and instead of a large blob of code which are accessible through different function names. The entire stub is self-contained. I have outlined this in a previous blog about Windows on ARM basics. ARM documentation defines a fixed definition as to how the layout of these tables should look (see “AArch64 vector tables”). For our purposes, the exception handler associated with handling interrupts which occur while execution is in user-mode is located at VBAR_EL1 at an offset of 0x80 (nt!KiKernelSp0InterruptHandler). It should be noted that the CPU core itself is what computes the necessary offset into the exception table and invokes the target function - not software itself.

Interestingly enough, this is not the end of the story. There is not just one single handler present. Depending on the state of the CPU (where execution was) when the interrupt happens, a different exception (interrupt) handler may be invoked. For instance, if execution was in kernel-mode when the interrupt occurs, the offset changes to 0x280 - and the target function becomes nt!KiKernelInterruptHandler. nt!KiUserInterruptHandler (offset 0x480) is invoked when an exception goes into a higher exception level (EL0 -> EL1) and at least one of the lower exception levels is runing ARM64. nt!KiUser32InterruptHandler is at offset 0x680 and is invoked when the same type of exception occurs, but all lower exception levels are ARM32 (different exception levels can be different architectures).

Interrupts, generally speaking on Windows, will always take an exception into EL1 - as this is where the various interrupt handlers are present. Given this, the SPSR_EL1 system register helps us to understand why a particular exception was taken into EL1. Because PSTATE is not directly accessible through a single system register, the Saved Program Status Register (SPSR) acts as a “snapshot” of sorts with relevant information about the current state of the CPU. This is needed for preserving and, later, restoring the state of the CPU at the time the exception (interrupt in our case) was handled.

After the current state of the CPU is known - there are a few more items of interest which are needed before, and in order to, dispatch the interrupt to software. The first is the CPU needs to know additionally where to return execution after the interrupt has taken place. There is a special system register, ELR_EL1 - the exception link register - which contains this address and is typically the next instruction to be executed (e.g., the first instruction that has not completed yet). In addition to the exception return address, we need to target a specific stack for the operation. At a bit of a higher-level, in software, interrupt service routines (ISRs) already have special reserved stacks for interrupt handling. This is because kernel stack space is limited, and we want to ensure that ISRs are not handled on stacks without any space left. At a bit of a lower level, the same thing happens conceptually. The CPU must also target a specific stack for the operation in the first place (while software on Windows handles the ISR stacks). Without compilcating things, generally speaking interrupts which occur in EL0 and then are trapped into EL 1 are handled on the stack pointer (SP) stored in the SP_EL0 register. For interrupts which occured when execution was already at EL1, obviously SP_EL1 would instead be used. This is why the interrupt handler for interrupts which happened while execution was in EL0 have Sp0 in the function name. Remember - interrupts are interrupting some sort of execution and need to be quick. The EL0 stack is the stack at whatever time the interrupt occured in EL0.

Our example will take a look at interrupts which occured while execution was in EL0 (nt!KiKernelSp0InterruptHandler). As mentioned, the first few things that happen (from the CPU’s perspective, and is transparent to the interrupt handler):

SPSR_EL1is updated with the currentPSTATE(the current state of the CPU). This is so the state can be restored later.- The actual PSTATE is updated with all information about the new execution environment (which is EL1, because the interrupt is trapped into EL1)

- The CPU actually executes the target interrupt handler (and selects the proper stack, in this case the EL0 stack)

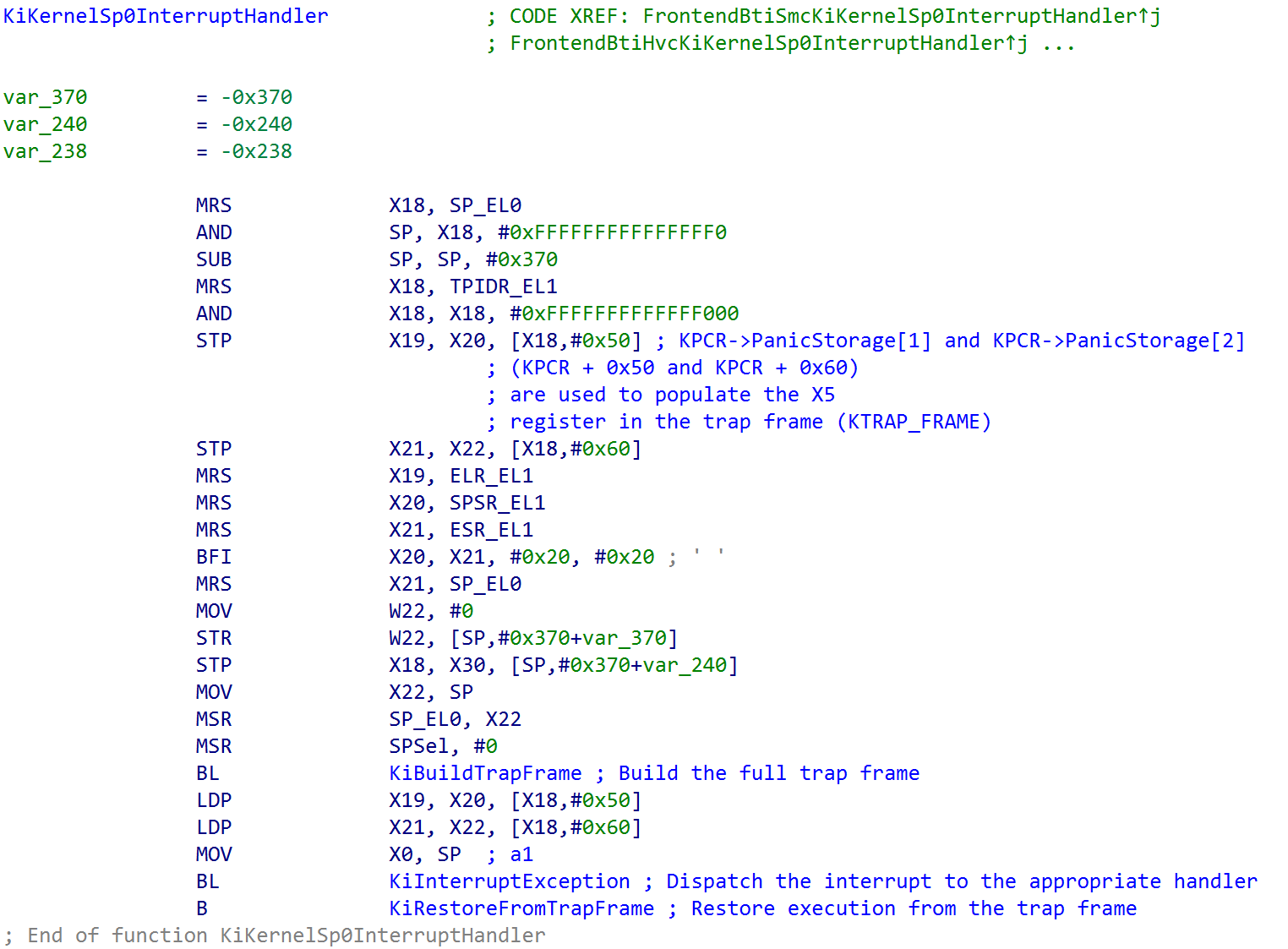

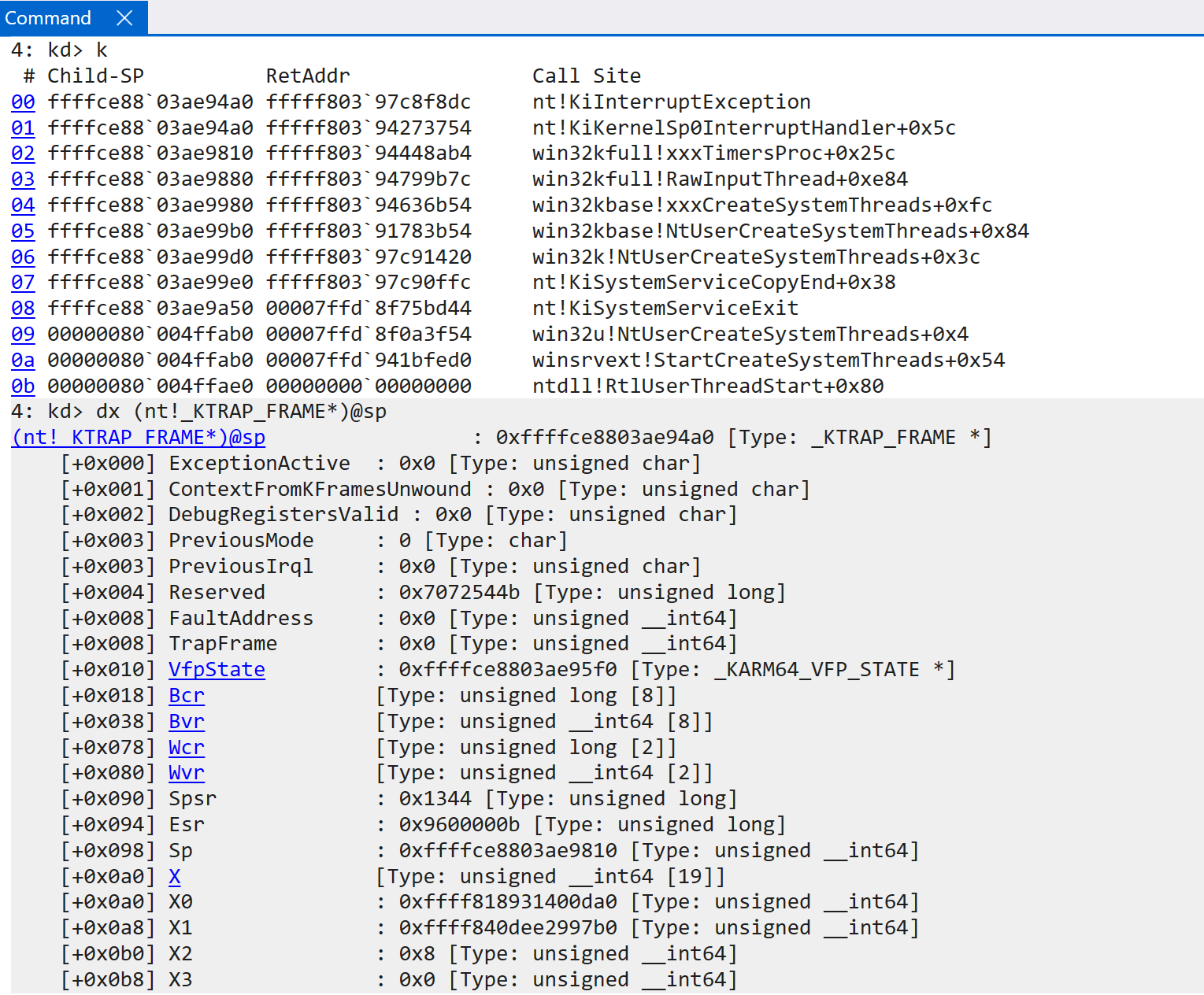

Execution now is in the interrupt handler (obviously setting a breakpoint on the interrupt handler is not a great idea!). The first thing nt!KiKernelSp0InterruptHandler does is to update the current execution environment as far as Windows is concerned. This includes allocating space on the SP_EL0 stack and also extracting a few pieces of information from the current KPCR structure (TPIDR_EL1/x18/xpr all hold the KPCR, as previously mentioned). Additionally, the ELR_EL1, SPSR_EL1, ESR_EL1, and SP_EL0 registers are preserved. Once these registers are preserved, the new SP_EL0 stack pointer is populated (since the old one is now preserved). The previously mentioned stack allocation is then to store trap frame which will is passed to the target interrupt handling operation (via nt!KiInterruptException). The target trap frame which will eventually be passed to nt!KiInterruptException is found directly on the stack (because execution is not returned from a return address on the stack since we are dealing with an exception and instead uses the exception link register and ERET) - although it still follow’s the typical calling convention, by copying this value also into X0.

nt!KiBuildTrapFrame invokes nt!KiCompletePartialTrapFrame (which has the aforementioned system registers, EL0 stack, etc. only at this point present in the trap frame) in order to grab more of what is needed. This includes the various debug registers and the SVE (Scalable Vector Excention) state. This function uses the stack space as the “output” parameter to store the final trap frame which is passed as the single argument to the function nt!KiInterruptException, which dispatches the correct interrupt handler in software.

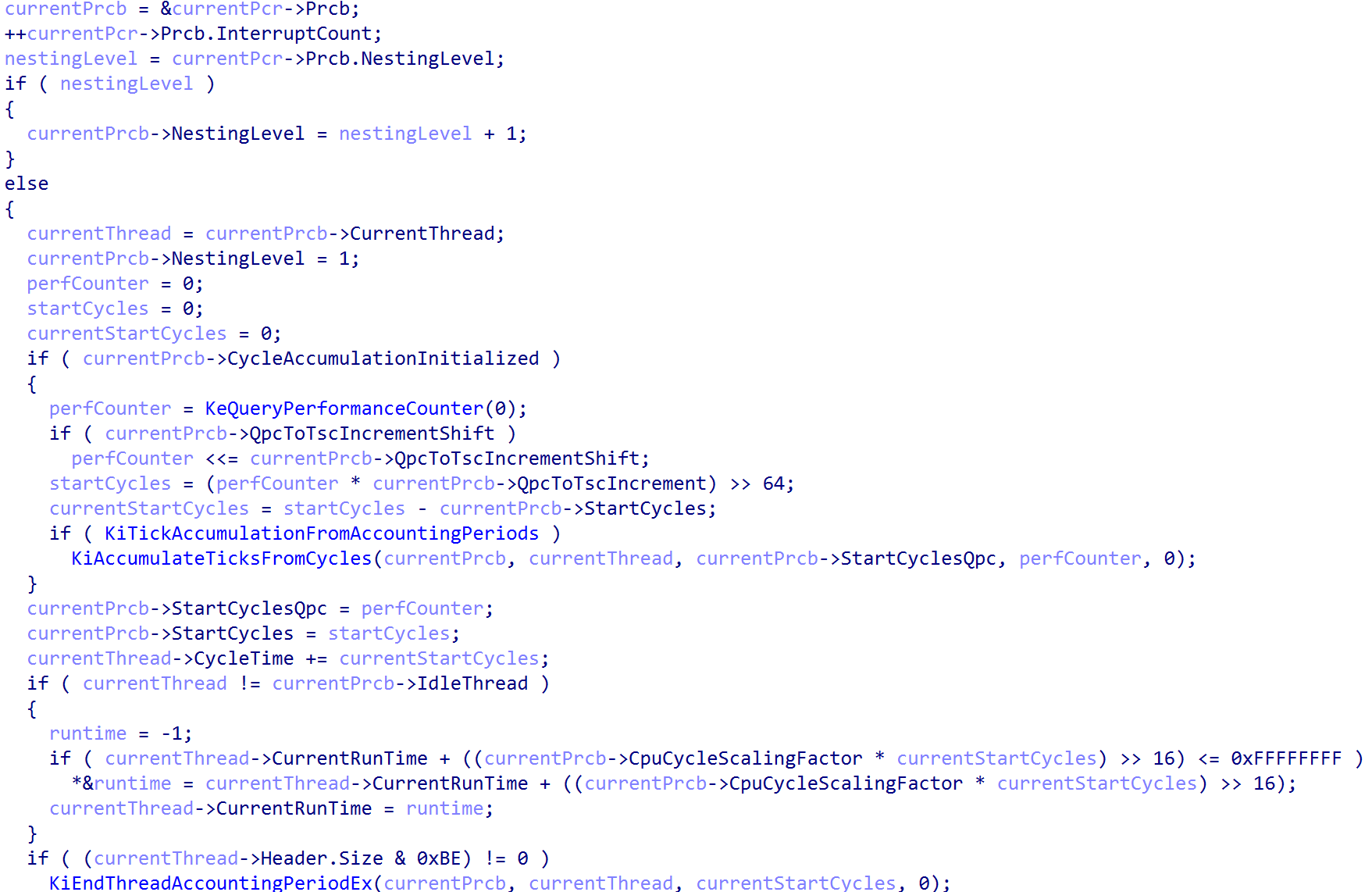

Before interacting with the interrupt controller (HalpInterruptController), a few “housekeeping” items first occur - including incrementing interrupt count and nesting level (if applicable - e.g., this is a nested interrupt) and updating the current CPU’s cycles/current runtime.

Note that in the process of creating this blog, my machine crashed a few times. Due to this, some of the values/etc. may change.

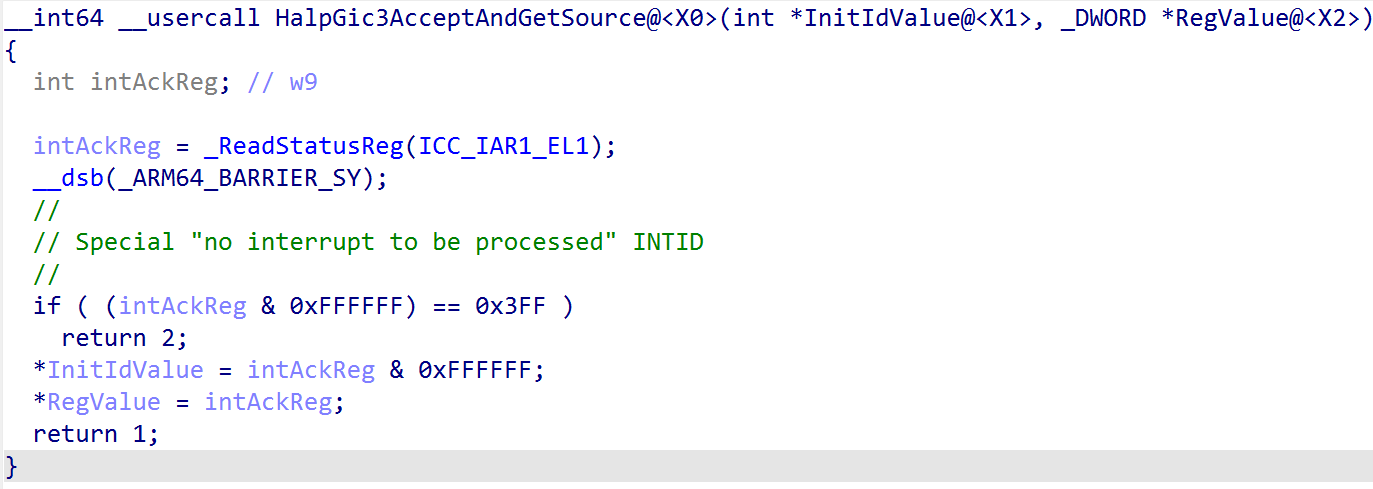

After this, the first bit of interrupt dispatching logic is called - and this is through nt!HalpGic3AccceptAndGetSource. This function simply reads from the ICC_IAR1_EL1 system register. This achieves two things: the first is that a read from this register actually acts as the acknowledgement, from software, of the interrupt which has been signaled. In addition - this also provides the caller of the read functionality with the target interrupt ID (INTID). This value returned can also be one of the “special” interrupt values - including 0x3ff, or 1023, which denotes that there is no pending interrupt with a high-enough priority to actually be forwarded to the CPU (or if for whatever reason the interrupt is not appropriate for the target CPU as well).

After the acknowledgement of the interrupt has occured, execution continues by grabbing the registered interrupt controller we have previously seen and iterating over all of the known/valid interrupt lines (INTIDs) and comparing this with the value which was provided by the interrupt acknowledgement register.

You will recall much earlier in the blog post when we talked about configuration of the various KINTERRUPT objects. Each of these objects, in the Vector field, contained what we saw was a target IRQL at which the target interrupt should be handled. Each of these vector values is mainted in the registered interrupt controller’s INTERRUPT_LINES member. Specifically, for a range of interrupt IDs the interrupt ID itself can be used as an index to find the appropriate information about how the target interrupt ID is to be handled. In this case we can see this is how the Vector is fetched, which gives us the target IRQL the CPU should be raised to in order to handle the target interrupt.

After the IRQL is raised (or lowered) to the target IRQL, the “main” brains of the routing operation, nt!KiPlayInterrupt, is invoked (unless there is not enough stack space. In this case, KxSwitchStackAndPlayInterrupt is invoked, using the current CPU’s ISR - or Interrupt Service Routine - stack). nt!KiPlayInterrupt has the following prototype:

KiPlayInterrupt (

_In_ KTRAP_FRAME* TrapFrame,

_In_ VectorFromInterruptLineData,

_In_ UINT8 Irql,

_In_ UINT8 PreviousIrql

);

Now brings up the conversation about “vectored interrupts”. As you can see, ARM64 does not have the same concept of vectored interrupts as x64 does - where the IDT can be directly indexed by the CPU itself. Instead, as we have seen, ARM implements a generic interrupt controller - meaning that there is one single interrupt handler and then software must find the appropriate interrupt handler. On ARM, we still have the Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) - but it is not directly accessed by the CPU itself - only the vector of exception handlers is directly invoked by the CPU.

Instead, the vector value from the interrupt line state (and KINTERRUPT object itself) is used as an index into the IDT, but this is a software defined vector - not a vector “contract” that is required by the interrupt controller (again, only the VBAR_EL1 table has a strong contract where the “high-level” interrupt handler must be present).

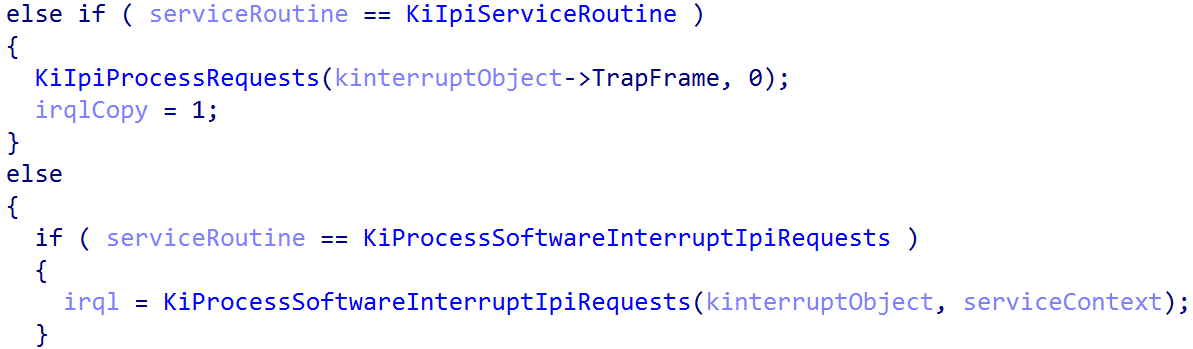

This allows us to extract the target KINTERRUPT object. From here, the target SerivceRoutine can be extracted. From here, there is a large if/else statement which determines if the interrupt needs further processing based on the target service routine (ISR).

After the target interrupt handler is invoked, nt!KiPlayInterrupt is responsible (if applicable) for some additional cleanup - including decrementing the nested interrupt level, updating the CPU cycle count, etc. From here, execution returns to the caller - nt!KiInterruptException. From here, nt!HalpGic3WriteEndOfInterrupt is invoked - which simply writes to the ICC_EOIR1_EL1 system register the interrupt ID which was handled.

The last thing which needs to occur is a restoration of the execution which was occuring when the interrupt took place. This occurs through the function nt!KiRestoreFromTrapFrame. This is a generic function, called by many exception handlers, which restores the execution state (via the preserved trap frame we showed at the beginning of the section of this blog) and performs the ERET, based on the target exception link register value, to EL0.

Virtualization and Interrupts

The implementation of virtual interrupts is a must for systems which are running virtualization software (like Hyper-V). Given that the Windows OS itself is virtualized, this means that virtualization and virtual interrupts are still very important constructs we have not talked about yet. There are a couple of important things to remember here - and that is there is still an additional traversal which occurs between EL0, EL1, and now EL2 with the addition of the hypervisor.

For virtual interrupts, the hypervisor configuration register (HCR_EL2) is responsible configuring the routing of physical interrupts. As previously shown, Hyper-V configures this register in its entry point. Hyper-V directly configures HCR_EL2.FMO and HCR_EL2.IMO - which, respectively, route physical interrupts (IRQs and FIQs) to EL2 (Hyper-V). However, HCR_EL2.TGE is not enabled for Hyper-V (trap general exceptions). Given this, there is some nuance about what these interrupts look like. From the ARM documentation, the following is said when HCR_EL2.IMO is set to 1:

When executing at any Exception level, and EL2 is enabled in the current Security state:

- Physical IRQ interrupts are taken to EL2, unless they are routed to EL3.

- When the value of HCR_EL2.TGE is 0, then Virtual IRQ interrupts are enabled.

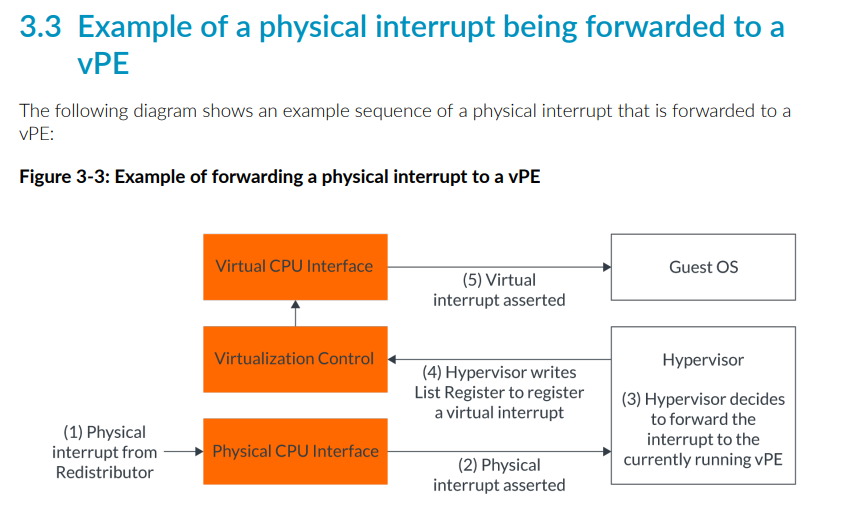

What this actually means is that physical IRQs are not actually routed to EL2. Instead, virtual IRQs (virtual interrupts) are enabled in the configuration of the hypervisor that Hyper-V performs. It is worth quickly making a distinction - virtual interrupts are terms used by both Hyper-V (Windows) and ARM. ARM does not have any knowledge of the OS when it comes to virtual interrupt configuration. Hyper-V, as we will see, also implements an additional level of abstraction for virtual interrupts (especially for guests). Windows Internals 7th Edition, Part 2 contains an entire section on “Virtual interrupts” - but it is worth talking about how ARM defines virtual interrupts first, and then moving on to the Hyper-V specific details. Virtual interrupts in general, for starters, represent interrupts which are seen by VMs/guests.

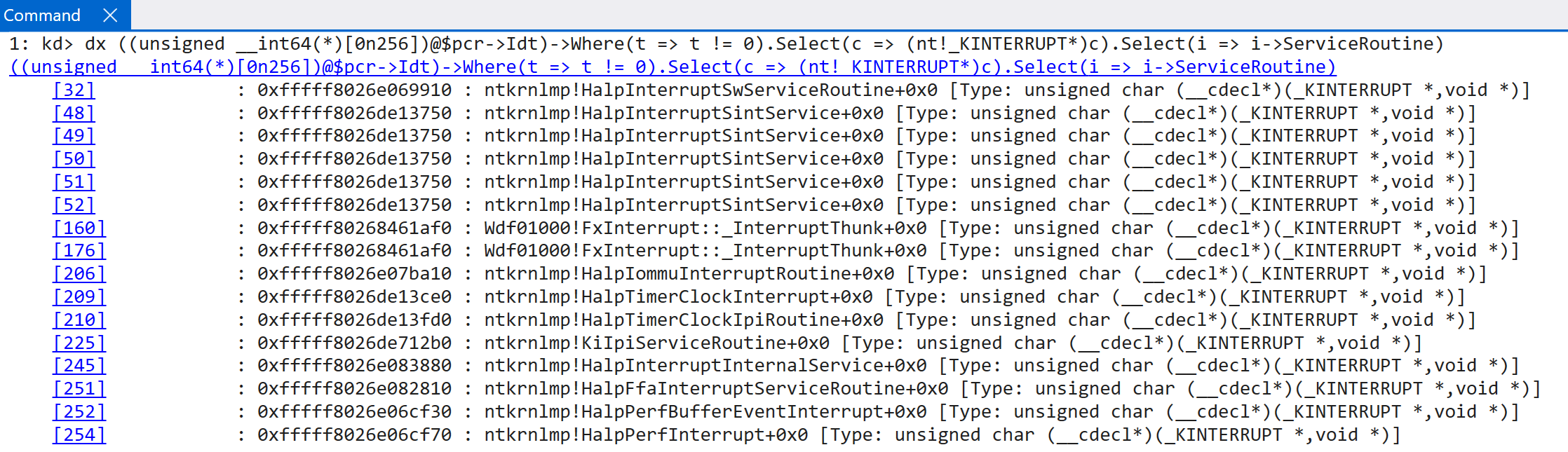

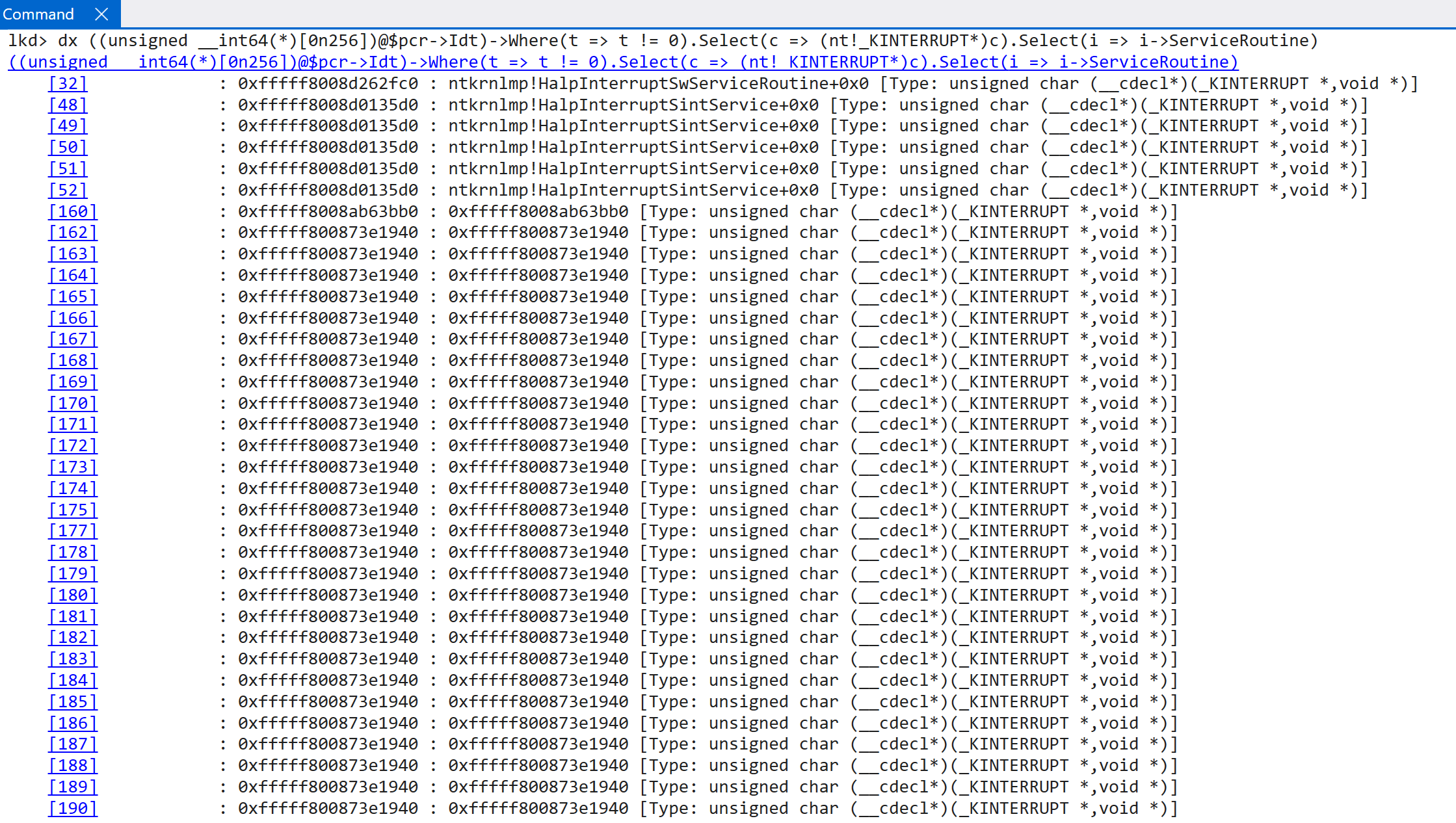

According to the TLFS, ARM64 systems actually expose a virtual GIC (this is done by software working with the CPU, as called out by the ARM documentation. This is because the distributor, reidstributor, etc. is explicitly called out as not providing virtualization for these and, thus, requires some help from software running in EL2. This is beyond the scope of this blog post and is something achieved by the hypervisor) - which “conforms to the ARM GIC architecture specification”. This means technically in our dynamic analysis we have been dealing with a virtual GIC - but this has, obviously, been transparent to us because as “the guest” (where the analysis is performed) we simply just access the “normal” registers associated with the interrupt controller (because GICv3 has the ability to virtualize the interrupt controller!). However, even though the root partition is often enlightened with additional information that guests may not be privy to, both root and guest partitions go through the virtualized GIC. This is also why the EXT_ENV member of the registered interrupt controller is important - and why one of the options is ExtEnvHvRoot, for the root partition. This can be seen be comparing the output of the IDTs between a true guest and the OS living in the root partition.

Guest:

Root parition (many other KINTERRUPT objects are truncated):

Before we derail ourselves too far, let’s keep examining the “ARM” view of virtual interrupts. ARM documentation on this subject is very helpful. Firstly, virtual interrupts target virtual CPUs (not VMs). The hypervisor uses ICH_XXX instead of the ICC_XXX interrupt registers for interacting with virtual interrupts (this also means that virtualization of the GIC is a “hardware” construct in the sense that there are dedicated system registers to configure the virtual GIC’s functionality). Parsing a list of system register writes, in Hyper-V, reveals (obviously) the presence of virtual interrupt configuration and management (ICH_HCR_EL2 is the effectively virutal interrupt configuration register):

0x14022760c sub_1402275D0 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_HCR_EL2, X8

As Windows Internals, 7th Edition, Part 2 calls out - Hyper-V is configured (but does not leverage) to support up to 16 virtual interrupt types. This conforms exactly to what ARM supports. One virtual interrupt is represented by a single ICH_LR<N>_EL2 register - where N is a value between 0 and 15 (16 total). A hypervisor write to one of these registers corresponds to the generation of a virtual interrupt. Again, by parsing Hyper-V, we can see several instances of the generation of a virtual interrupt:

0x140228a7c sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR1_EL2, X8

0x140228af0 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR0_EL2, X8

0x140228bdc sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR2_EL2, X8

0x140228c38 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR15_EL2, X8

0x140228c48 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR14_EL2, X8

0x140228c58 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR13_EL2, X8

0x140228c68 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR12_EL2, X8

0x140228c78 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR11_EL2, X8

0x140228c88 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR10_EL2, X8

0x140228c98 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR9_EL2, X8

0x140228ca8 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR8_EL2, X8

0x140228cb8 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR7_EL2, X8

0x140228cc8 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR6_EL2, X8

0x140228cd8 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR5_EL2, X8

0x140228ce8 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR4_EL2, X8

0x140228cf8 sub_140228A30 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR3_EL2, X8

0x140228fe4 sub_140228F78 MSR c12 #4 MSR ICH_LR1_EL2, X8

This register includes important information - such as the virtual interrupt ID (vINTID), interrupt priority, etc. When the hypervisor writes to the target register, the virtual interrupt is injected into the guest. ARM’s documentation provides a nice visual here.

So we now have the actual underlying mechanism as to how the hypervisor is able to, using the provided CPU registers and hardware functionality exposed by GICv3, deliver a virtual interrupt to a target virtual CPU. However, Hyper-V now has an additional level of abstraction - using the “synthetic interrupt controller” - in order to deliver interrupts to synthetic devices (like virtualized keyboards, mice, etc.). The synthetic interrupt controller delivers two types of interrupts to virtual CPUs: those which come from hardware/devices (external) and also synthetic interrupts (which come from Hyper-V and are not generated by hardware).

The TLFS defines the “synthetic” interrupt controller as a set of extensions that are provided in addition to the already-existing interrupt controller features. The synthetic interrupt controller is leveraged by Hyper-V to not only deliver interrupts generated from physical hardware, to the guest (or root partition, which is the host OS), but to also add an additional level of abstraction over various message channels (defined by the TLFS) for other special kinds of interrupts to be delivered, such as the hypervisor directly delivering a message to a target partition (in the case of an intercept, for example) or inner-partition communication. Some of these message types can be seen below:

typedef enum

{

HvMessageTypeNone = 0x00000000, // Memory access messages

HvMessageTypeUnmappedGpa = 0x80000000,

HvMessageTypeGpaIntercept = 0x80000001, // Timer notifications

HvMessageTimerExpired = 0x80000010, // Error messages

HvMessageTypeInvalidVpRegisterValue = 0x80000020,

HvMessageTypeUnrecoverableException = 0x80000021,

HvMessageTypeUnsupportedFeature = 0x80000022,

HvMessageTypeTlbPageSizeMismatch = 0x80000023, // Trace buffer messages

HvMessageTypeEventLogBuffersComplete = 0x80000040, // Hypercall intercept.

HvMessageTypeHypercallIntercept = 0x80000050, // Platform-specific processor intercept messages

HvMessageTypeX64IoPortIntercept = 0x80010000,

HvMessageTypeMsrIntercept = 0x80010001,

HvMessageTypeX64CpuidIntercept = 0x80010002,

HvMessageTypeExceptionIntercept = 0x80010003,

HvMessageTypeX64ApicEoi = 0x80010004,

HvMessageTypeX64LegacyFpError = 0x80010005,

HvMessageTypeRegisterIntercept = 0x80010006,

} HV_MESSAGE_TYPE;

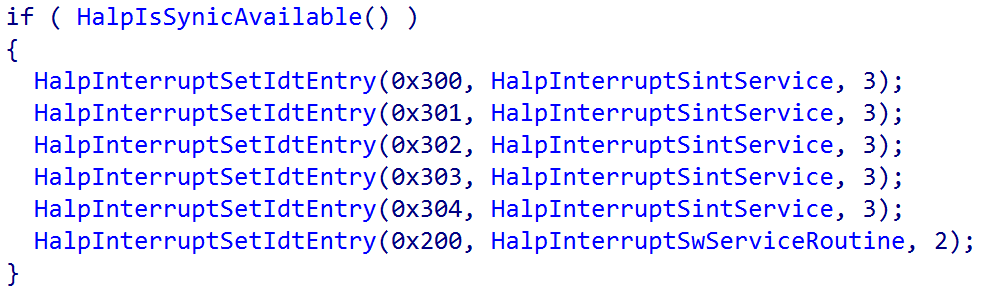

The nt!HalpInterruptSintService is actually the interrupt handler for handling synthetic interrupt controller-delivered interrupts (messages and/or interrupts targeting synthetic devices, which means for guests this is the primary ISR that is ever invoked). This can be seen by the result of a call to nt!HalpIsSynicAvailable - which enlightens the guest/root partition as to the presence of the synthetic controller. If it is present, the nt!HalpInterruptSintService routine is registered with a vector value of 0x30X - which means that the target IRQL is that of 3 and also that interrupt lines (INTIDs) 1, 2, 3, and 4 are all considered virtual interrupts because they are handled by the virtual interrupt handler. This means the hypervisor is responsible for forwarding (injecting) these interrupts to the guest. The hypervisor always receives the interrupt, and can forward it to the guest (or root partition in our case) if it is necessary (not all physical interrupt lines are associated with virtual interrupts, and not all physical devices may have an associated synthetic/virtualized device)

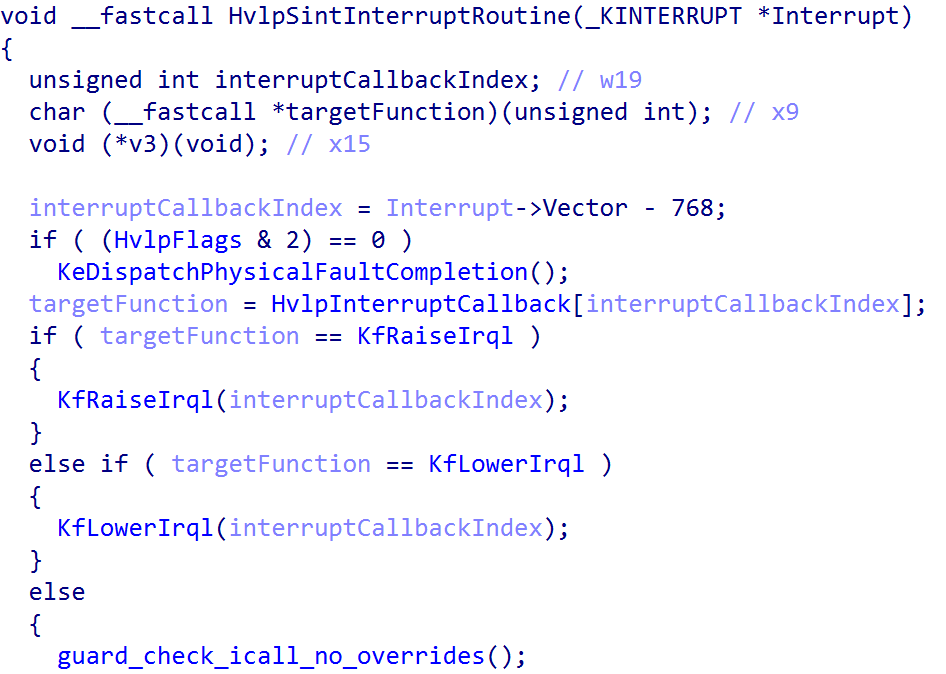

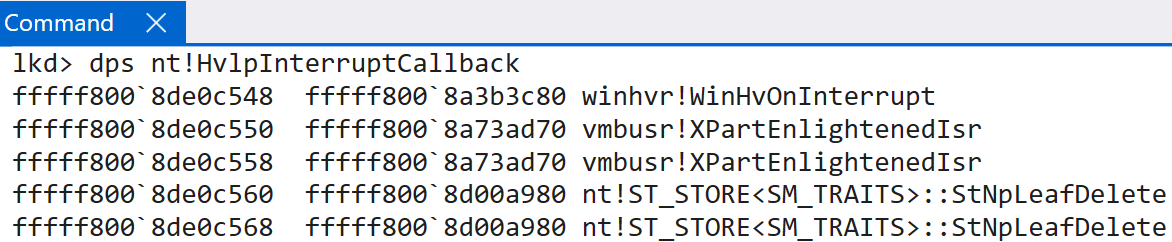

nt!HalpInterruptSintService then goes on to invoke nt!HvlpSintInterruptRoutine. This routine is responsible for using the vector value (subtracting 768 is subtracting 0x300, which removes the IRQL masked to the vector, of 3, from the operation) to index the nt!HvlpInterruptCallback table. Note that the NtNpLeafDelete is a side effect of symbol collision. For functions with identical code, the symbols get mashed into one single symbol. These two functions are simply ret NO-OP operations.

There are 5 total valid entries here (because as we saw earlier, vector values 0x300 through 0x304 use this service routine, so the valid indexes are 0 - 4 - a total of 5). Even Windows Internals, 7th Edition, Part 2 calls out that “vectors 30 - 34 are always used for Hyper-V related [VMBus] interrupts”. Technically index 0 (0x300) is used for hypervisor interrupts, and indexes 1 - 4 are used for VMBus interrupts. One thing that is important to note - if an interrupt is to arrive to a guest, it always first goes to the root partition. If the guest partition then needs the interrupt (for instance, if it has a synthetic device that is emulating the real physical devices, like a keyboard) the root partition will then assert an interrupt to the guest using the VMBus protocol (used for inner-partition communication). This is also why we see such a disparity in IDTs between root partitions (the host OS) and the guest OS where we are doing our dynamic analysis.

Note that the below tables differ based on if the target OS is the root or guest partition.

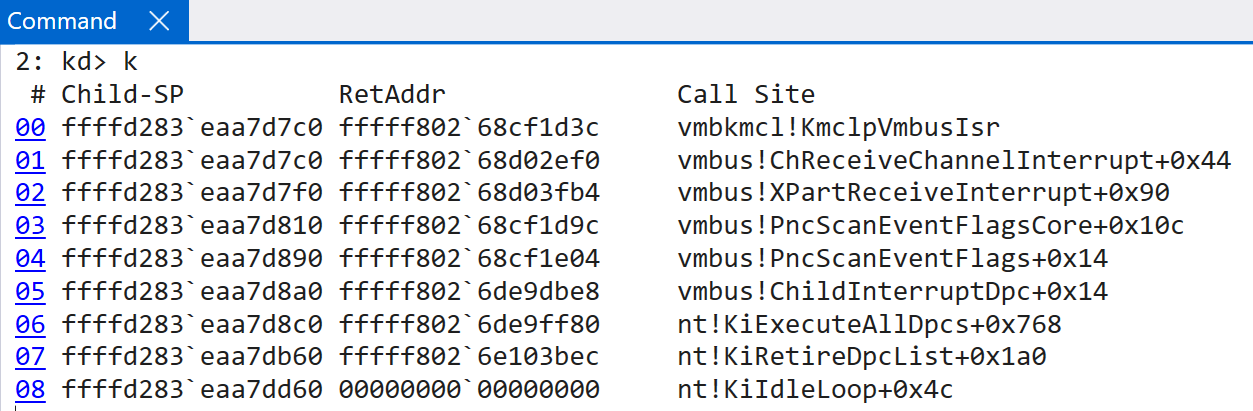

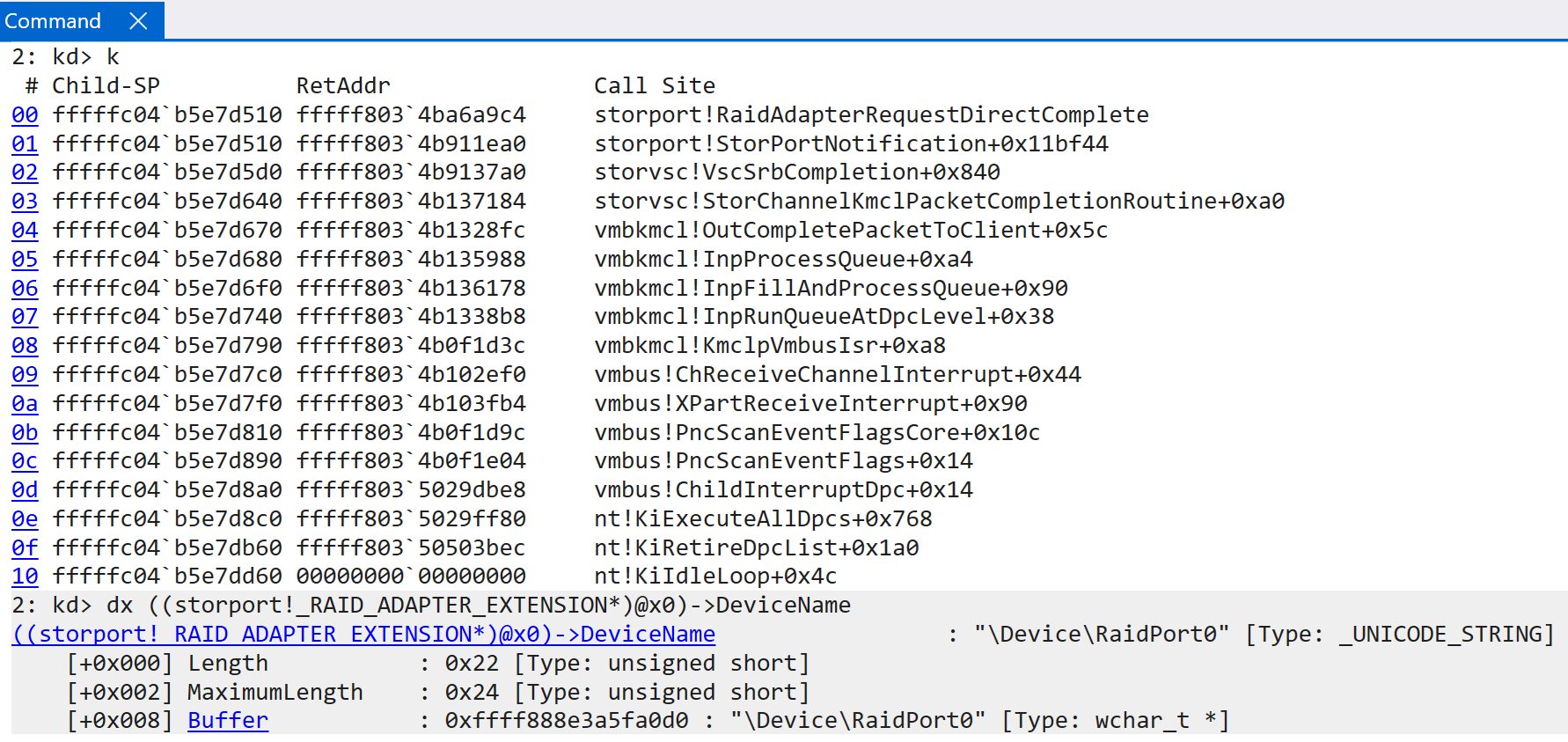

So how do child partitions, for example, receive interrupts from the root partition in order to send them to the target handler? vmbus!XPartEnlightenedIsr is the main target here. As other researchers have mentioned these functions possess the functionality necessary to pass the virtual interrupt to the appropriate handlers. vmbus!XPartEnlightenedIsr simply queues a DPC with the target routine being that of vmbus!ChildInterruptDpc. This function eventually invokes vmbus!XPartReceiveInterrupt - to receive the interrupt from the root partition (or hypervisor). This invokes the lower-level function, vmbus!ChReceiveChannelInterrupt which then invokes the true ISR - vmbkmcl!KmclpVmbusIsr (or vmbkmcl!KmclpVmbusManualIsr).

This ISR is responsible for eventually determining how to handle the interrupt from Hyper-V, by parsing the message protocol. Eventually the vmbkmcl.sys driver (the VMBus common library driver) is invoked. This driver handles the majority of the parsing and results in the target operation occuring. In this example, the guest receives an interrupt, from the hypervisor, which results in a call to vmbkcml!InpFillAndProcessQueue - which is responsible for eventually dispatching the target. In this case, the synthetic SCSI driver (storvsc.sys). This request is then forwarded on to the VM’s storport.sys driver - which indicates that the interrupt was sent to this guest in order to notify the Store Port driver about a request which was completed (RequestDirectComplete). This particular request ended up invoking storport!RaidAdapterRequestDirectComplete, passing in the associated RAID_ADAPTER_EXTENSION structure provided from the notification request. In conclusion, this is how the guest partition fulfills a particular request at the synthetic device level, upon request from the root partition or hypervisor as a result of some physical device interrupt.

VTLs, Secure Kernel Interrupts, and Secure Interrupts

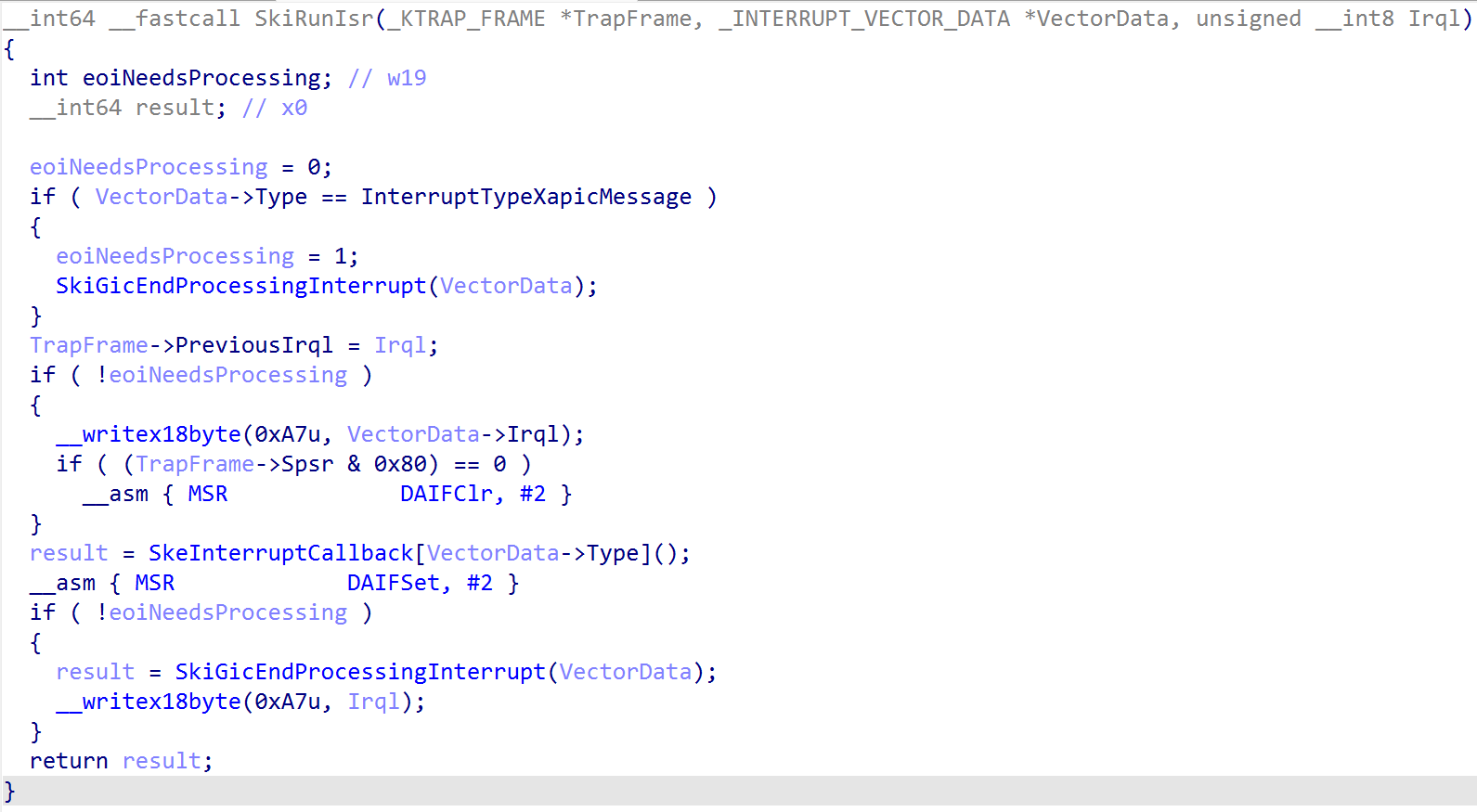

This section is not specific to ARM64 - and thus it will just be short, as it is for completeness sake. However, it is worth talking about because interrupt handling in the Secure Kernel is completely different than x64 (in fact, almost all of the functions related to interrupts do not exist in x64 as they do on ARM, and vice-versa). The TLFS defines that each VTL has its own virtual interrupt controller (in our case, this means the Secure Kernel in VTL 1 has its own virtual GIC to interface with, that Hyper-V configures, which is separate from the root partition’s virtual GIC in VTL 0). The Secure Kernel has a very similar function to NT, securekernel!SkiGicInitialize. Additionally, securekernel!SkiGicData effectivel mimics nt!HalpGic3 in NT. The main functionality in the Secure Kernel is securekernel!SkiRunIsr. This function invokes the appopriate function in the securekernel!SkeInterruptCallback table.

Although the Secure Kernel does not accept any kind of file I/O, etc. - it still needs the ability to handle interrupts due to something known as secure interrupts and secure intercepts. Secure interrupts are interrupts that are trapped into VTL 1 as a result of some action in VTL 0 (thanks to the hypervisor). On ARM64 systems, the Secure Kernel is responsible for registering with the synthetic interrupt controller (securekernel!ShvlpInitializeSynic). This allows the Secure Kernel to receive a synthetic interrupt as a result of an intercept, for example. A great example of this is HyperGuard. How does this work? On the latest insider preview build of Windows, the SkeInterruptCallback (notice the similarity to the synthetic handler routine from NT we previously-showed, nt!HvlpSintInterruptRoutine, and the current one. Both are synthetic interrupt handlers) table is as follows:

ShvlpVinaHandlerShvlpTimerHandlerShvlpInterceptHandler-> The secure intercept handlerSkiHandleFreezeIpiSkiHandleCallbackSkiHandleIpi

In our case, the “secure interrupt” handler we care about is the ShvlpInterceptHandler. As Yarden calls out in her blog, the intercept functionality registers with Hyper-V a list of actions to intercept. For example, certain writes or accesses to ARM64 system registers will result in Hyper-V injecting a synthetic interrupt into the Secure Kernel, allowing the Secure Kernel to examine such an operation inline of it occuring and preventing (causing a crash via ShvlRaiseSecureFault, for example) or letting the action occur. Additionally, even other items like hyper calls can be intercepted. This is the basis for HyperGuard, for example.

Windows on ARM Interrupts - WinDbg

Before ending this blog post, I thought it might be prudent to just outline some nuances with WinDbg at the time of this writing. Some commands, like !idt, just simply do not work on WinDbg because of the differences in interrupt handling. However, I wanted to call out a few useful commands I found that are specific to ARM:

!gicc-> GIC CPU interface analysis!gicd-> GIC distributor analysis!gicr-> GIC redistributor analysis

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this blog post! I enjoyed writing it!

Resources

- Matt Suiche blog: https://www.msuiche.com/posts/smbaloo-building-a-rce-exploit-for-windows-arm64-smbghost-edition/

- UEFI spec: https://uefi.org/sites/default/files/resources/ACPI_Spec_6.6.pdf

- Microsoft: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/bringup/acpi-system-description-tables

- Code Machine: https://codemachine.com/articles/arm_assembler_primer.html

- BSOD Tutorials: https://bsodtutorials.wordpress.com/2020/01/09/hardware-interrupts-irqs-and-irqls-part-1/

- ARM GIC Specification: https://developer.arm.com/documentation/ihi0069/hb/?lang=en

- Hyper-V internals: https://hvinternals.blogspot.com/2015/10/hyper-v-internals.html