Exploit Development: Between a Rock and a (Xtended Flow) Guard Place: Examining XFG

Introduction

Previously, I have blogged about ROP and the benefits of understanding how it works. Not only is it a viable first-stage payload for obtaining native code execution, but it can also be leveraged for things like arbitrary read/write primitives and data-only attacks. Unfortunately, if your end goal is native code execution, there is a good chance you are going to need to overwrite a function pointer in order to hijack control flow. Taking this into consideration, Microsoft implemented Control Flow Guard, or CFG, as an optional update back in Windows 8.1. Although it was released before Windows 10, it did not really catch on in terms of “mainstream” exploitation until recent years.

After a few years, and a few bypasses along the way, Microsoft decided they needed a new Control Flow Integrity (CFI) solution - hence XFG, or Xtended Flow Guard. David Weston gave an overview of XFG at his talk at BlueHat Shanghai 2019, and it is pretty much the only public information we have at this time about XFG. This “finer-grained” CFI solution will be the subject of this blog post. A few things before we start about what this post is and what it isn’t:

- This post is not an “XFG internals” post. I don’t know every single low level detail about it.

- Don’t expect any bypasses from this post - this mitigation is still very new and not very explored.

- We will spend a bit of time understanding what indirect function calls are via function pointers, what CFG is, and why XFG is a very, very nice mitigation (IMO).

This is simply going to be an “organized brain dump” and isn’t meant to be a “learn everything you need to know about XFG in one sitting” post. This is just simply documenting what I have learned after messing around with XFG for a while now.

The Blueprint for XFG: CFG

CFG is a pretty well documented exploit mitigation, and I have done my fair share of documenting it as well. However, for completeness sake, let’s talk about how CFG works and its potential shortcomings.

Note that before we begin, Microsoft deserves recognition for being one of the leaders in implementing a Control Flow Integrity (CFI) initiative and among the first to actually release a CFI solution.

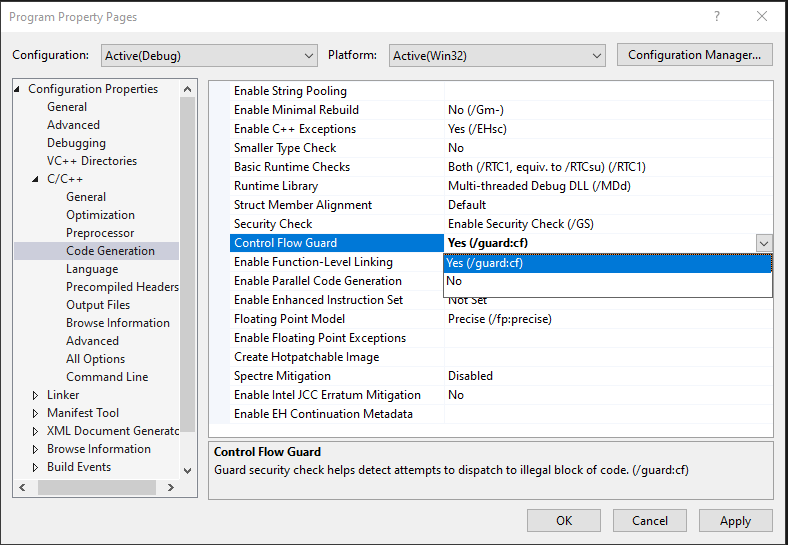

Firstly, to enable CFG, a program is compiled and linked with the /guard:cf flag. This can be done through the Microsoft Visual Studio tool cl (which we will look at later). However, more easily, this can be done by opening Visual Studio and navigating to Project -> Properties -> C/C++ -> Code Generation and setting Control Flow Guard to Yes (/guard:cf)

CFG at this point would now be enabled for the program - or in the case of Microsoft binaries, they would already be CFG enabled (most of them). This causes a bitmap to be created, which essentially is made up of all functions within the process space that are “protected by CFG”. Then, before an indirect function call is made (we will explore what an indirect call is shortly if you are not familiar), the function being called is sent to a special CFG function. This function checks to make sure that the function being called is a part of the CFG bitmap. If it is, the call goes through. If it isn’t, the call fails.

Since this is a post about XFG, not CFG, we will skip over the technical details of CFG. However, if you are interested to see how CFG works at a lower level, Morten Schenk has an excellent post about its implementation in user mode (the Windows kernel has been compiled with CFG, known as kCFG, since Windows 10 1703. Note that Virtualization-Base Security, or VBS, is required for kCFG to be enforced. However, even when VBS is disabled, kCFG has some limited functionality. This is beyond the scope of this blog post).

Moving on, let’s examine how an indirect function call (e.g. call [rax] where RAX contains a function address or a function pointer), which initiates a control flow transfer to a different part of an application, looks without CFG or XFG. To do this, let’s take a look at a very simple program that performs a control flow transfer.

Note that you will need Microsoft Visual Studio 2019 Preview 16.5 or greater in order to follow along.

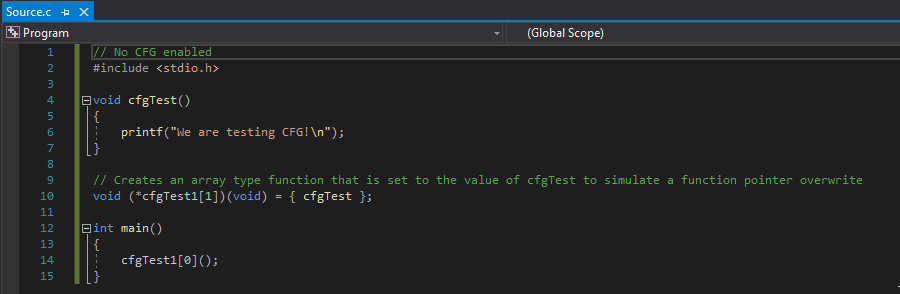

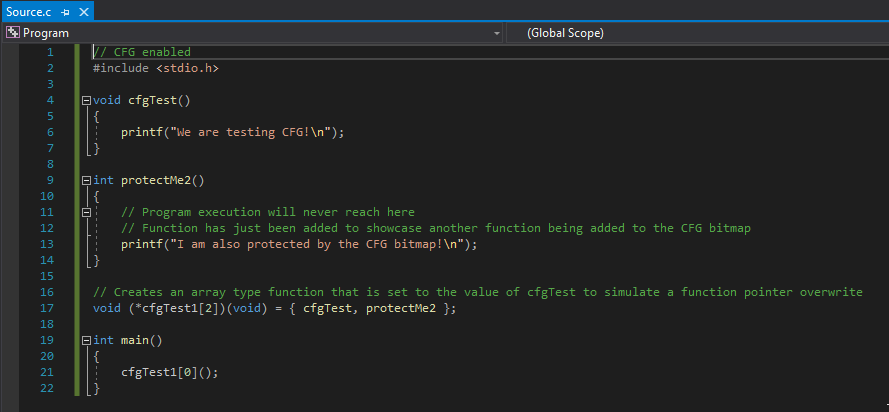

Let’s talk about what is happening here. Firstly, this code is intentionally written this way and is obviously not the most efficient way to do this. However, it is done this way to help simulate a function pointer overwrite and the benefits of XFG/CFG.

Firstly, we have a function called void cfgTest() that just prints a sentence. This function is then assigned to a function pointer called void (*cfgTest1), which actually is an array. Then, in the main() function, the function pointer void (*cfgTest1) is executed. Since void (*cfgtest1) is pointing to void cfgTest(), this will actually just cause void (*cfgtest1) to just execute void cfgTest(). This will create a control flow transfer, as the main() function will perform a call to the void (*cfgTest1) function, which will then call the void cfgTest() function.

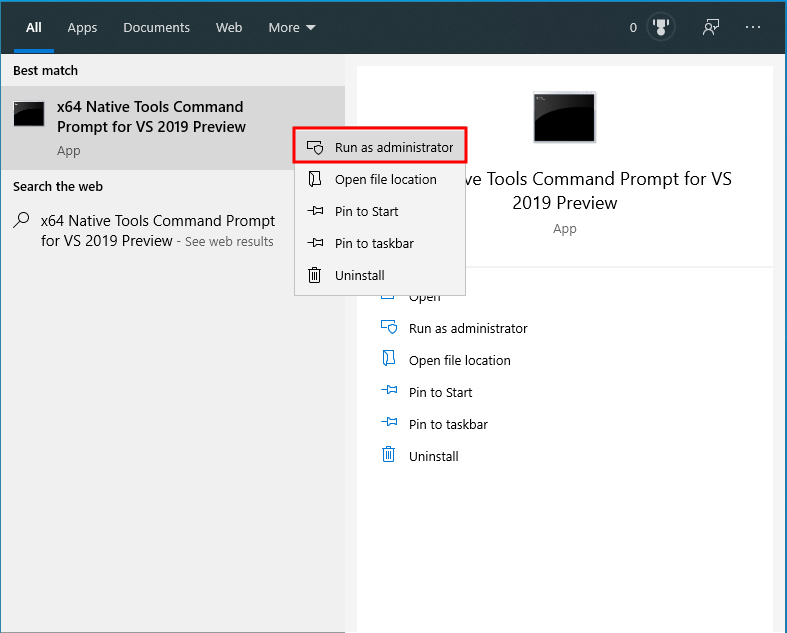

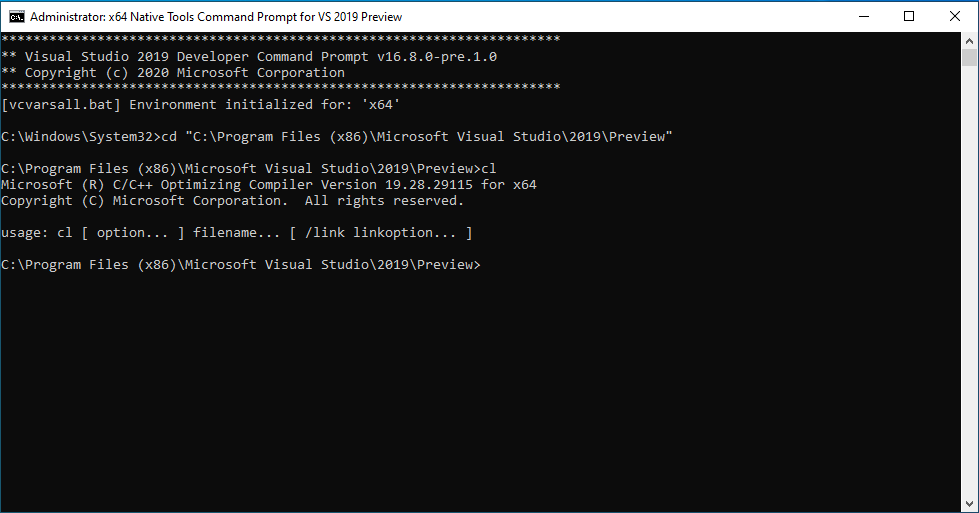

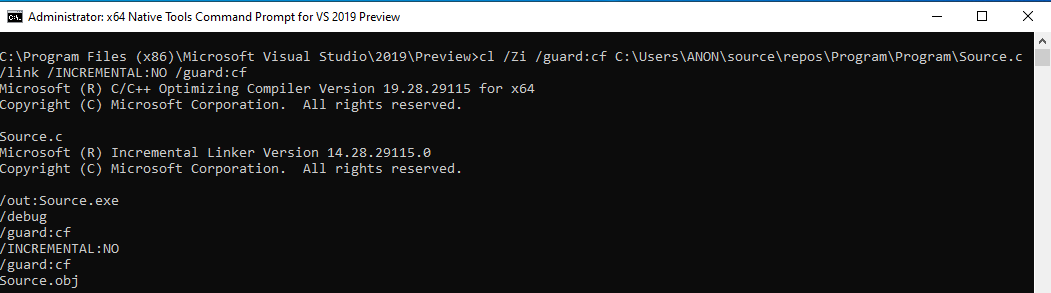

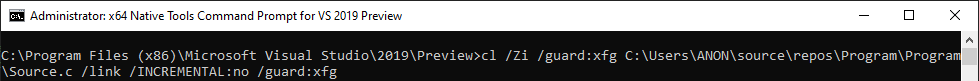

To compile with the command line tool cl, type in “x64 Native Tools Command Prompt for VS 2019 Preview” in the Start menu and run the program as an administrator.

This will drop you into a special Command Prompt. From here, you will need to navigate to the installation path of Visual Studio, and you will be able to use the cl tool for compilation.

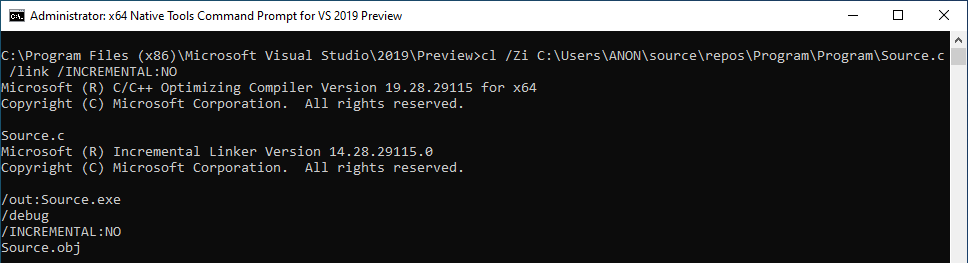

Let’s compile our program now!

The above command essentially compiles the program with the /Zi flag and the /INCREMENTAL:NO linking option. Per Microsoft Docs, /Zi is used to create a .pdb file for symbols (which will be useful to us). /INCREMENTAL:NO has been set to instruct cl not to use the incremental linker. This is because the incremental linker is essentially used for optimization, which can create things like jump thunks. Jump thunks are essentially small functions that only perform a jump to another function. An example would be, instead of call function1, the program would actually perform a call j_function1. j_function1 would simply be a function that performs a jmp function1 instruction. This functionality will be turned off for brevity. Since our “dummy program” is so simple, it will be optimized very easily. Knowing this, we are disabling incremental linking in order to simulate a “Release” build (we are currently building “Debug” builds) of an application, where incremental linking would be disabled by default. However, none of this is really prevalent here - just a point of contention to the reader. Just know we are doing it for our purposes.

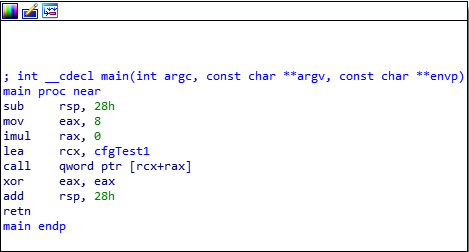

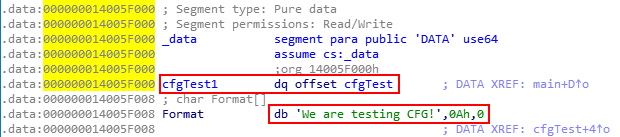

The result of the compilation command will place the output file, named Source.exe in this case, into the current directory along with a symbol file (.pdb). Now, we can open this application in IDA (you’ll need to run IDA as an administrator, as the application is in a privileged directory). Let’s take a look at the main() function.

Let’s examine the assembly above. The above function loads the void (*cfgTest1) function pointer into RCX. Since void (*cfgTest1) is a function pointer to an array, the value in RCX itself isn’t what is needed to jump to the array. Only when RCX is dereferenced in the call qword ptr [rcx+rax] instruction does program execution actually perform a control flow transfer to void (*cfgTest1)’s first index - which is void cfgTest(). This is why call qword ptr [rcx+rax] is being performed, as RAX is the position in the array that is being indexed.

Taking a look at the call instruction in IDA, we can see that clearly this will redirect program execution to void cfgTest().

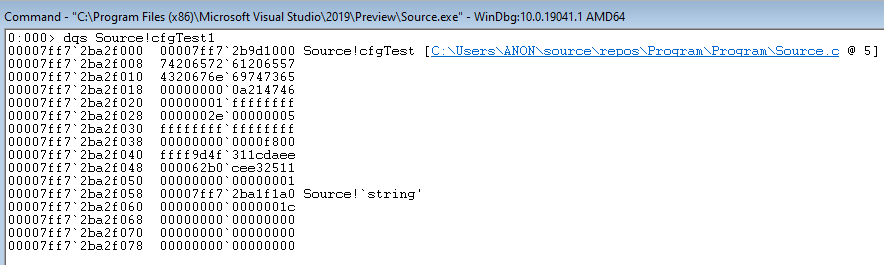

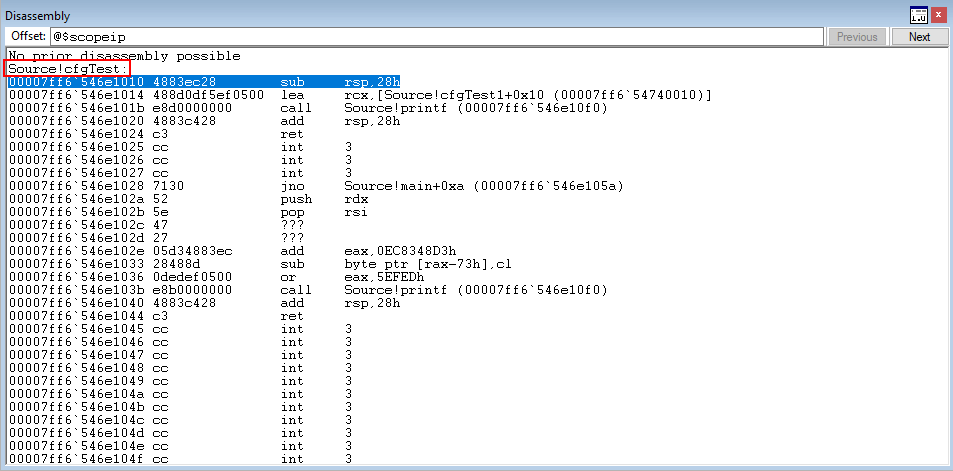

Additionally, in WinDbg, we can see that Source!cfgTest1, which is a function, points to Source!cfgTest.

Nice! We know that our program will redirect execution from main() to void (*cfgTest1) and then to void cfgTest()! Let’s say as an attacker, we had an arbitrary write primitive and we were able to overwrite what void (*cfgTest1) points to. We could actually change where the application actually ends up calling! This is not good from a defensive perspective.

Can we mitigate this issue? Let’s go back and recompile our application with CFG this time and find out.

This time, we add /guard:cf as a flag, as well as a linking option.

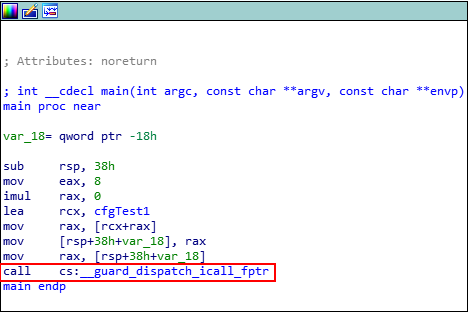

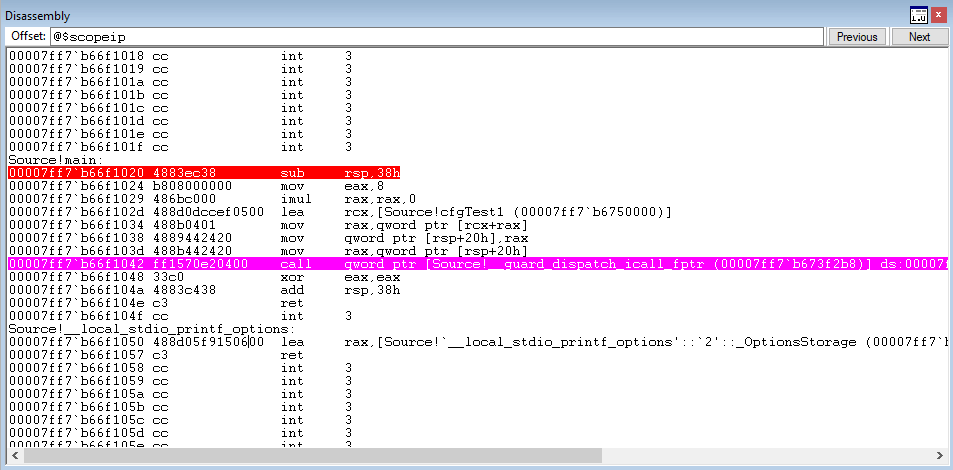

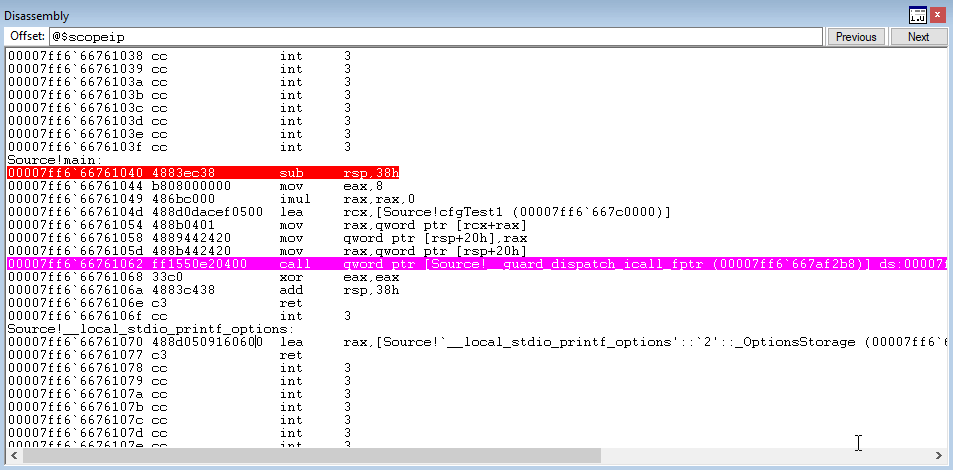

Disassembling the main() function in IDA again, we notice things look a bit different.

Very interesting! Instead of making a call directly to void (*cfgTest1) this time, it seems as though the function __guard_disaptch_icall_fptr will be invoked. Let’s set a breakpoint in WinDbg on main() and see how this looks after invoking the CFG dispatch function.

After setting a breakpoint on the main() function, code execution hits the CFG dispatch function.

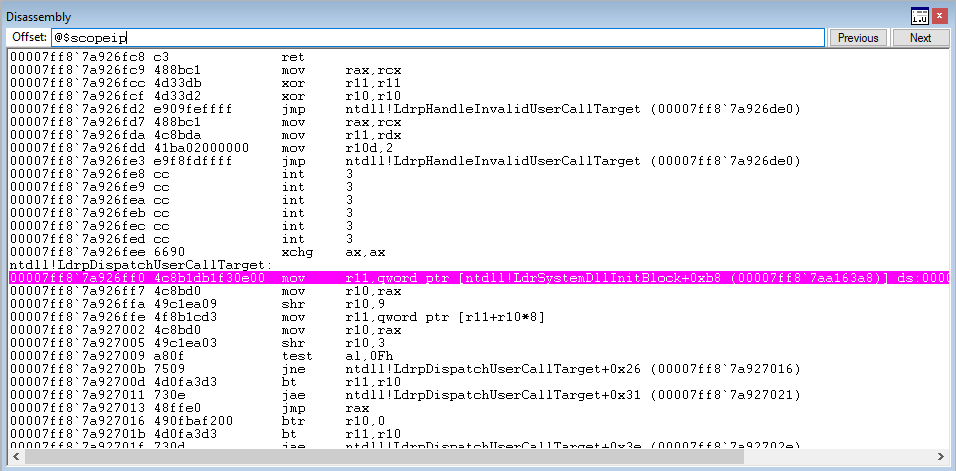

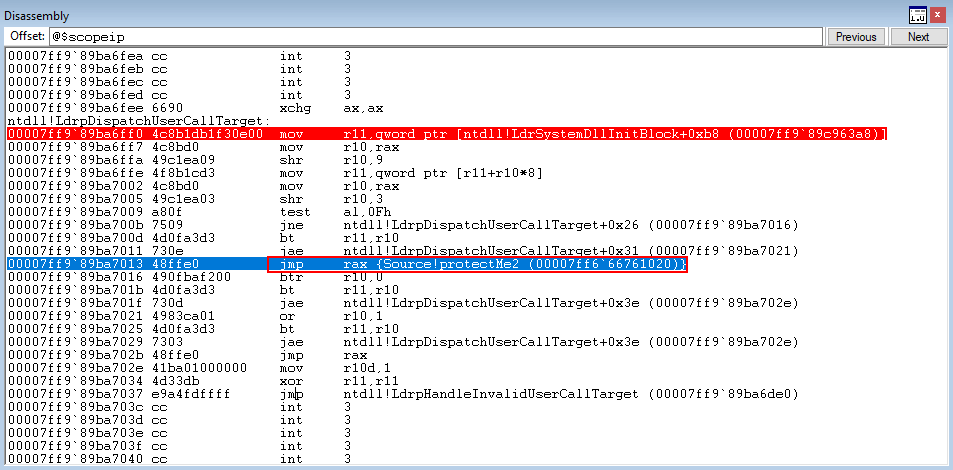

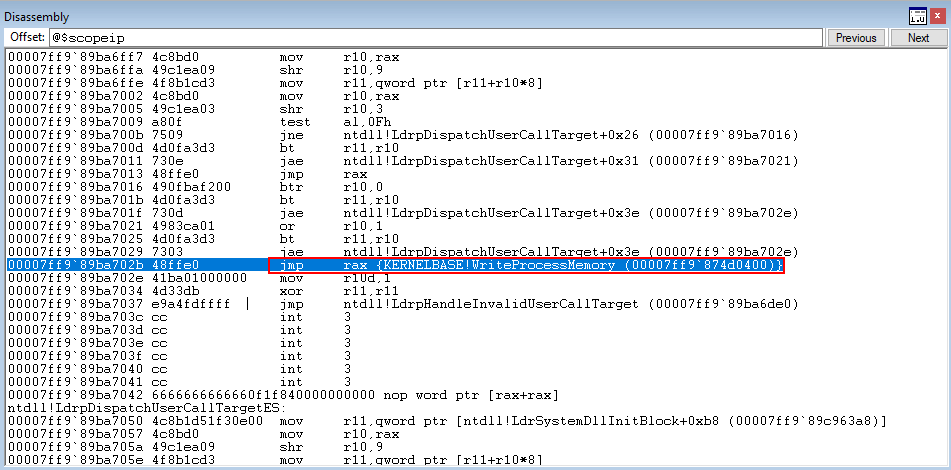

The CFG dispatch function then performs a dereference and jumps to ntdll!LdrpDispatchUserCallTarget.

We won’t get into the technical details about what happens here, as this post isn’t built around CFG and Morten’s blog already explains what will happen. But essentially, at a high level, this function will check the CFG bitmap for the Source.exe process and determine if the void cfgTest() function is a valid target (a.k.a if it’s in the bitmap). Obviously this function hasn’t been overwritten, so we should have no problems here. After stepping through the function, control flow should transfer back to the void cfgTest() function seamlessly.

Execution has returned back to the void cfgTest() function. Additionally what is nice, is the lack of overhead that CFG put on the program itself. The check was very quick because Microsoft opted to use a bitmap instead of indexing an array or some other structure.

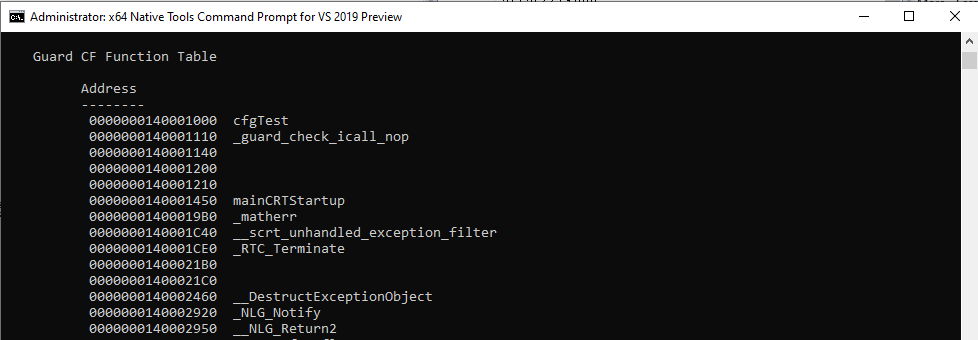

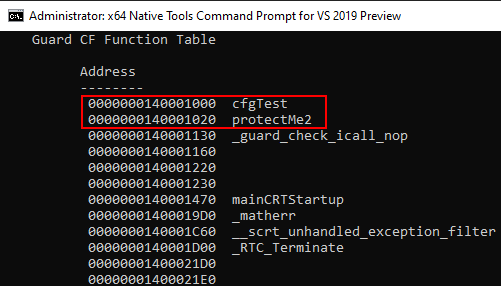

You can also see what functions are protected by the CFG bitmap by using the dumpbin tool within the Visual Studio installation directory and the special Visual Studio Command Prompt. You can use the command dumpbin /loadconfig APPLICATION.exe to view this.

Let’s see if we can take this even further and potentially show why XFG is defintley a better/more viable option than CFG.

CFG: Potential Shortcomings

As mentioned earlier, CFG checks functions to make sure they are part of the “CFG bitmap” (a.k.a protected by CFG). This means a few things from an adversarial perspective. If we were to use VirtualAlloc() to allocate some virtual memory, and overwrite a function pointer that is protected by CFG with the returned address of the allocation - CFG would make the program crash.

Why? VirtualAlloc() (for instance) would return a virtual address of something like 0xdb0000. When the application in question was compiled with CFG, obviously this memory address wasn’t a part of the application. Therefore, this address wouldn’t be “protected by CFG” and the program would crash. However, this is not very practical. Let’s think about what an adversary tries to accomplish with ROP.

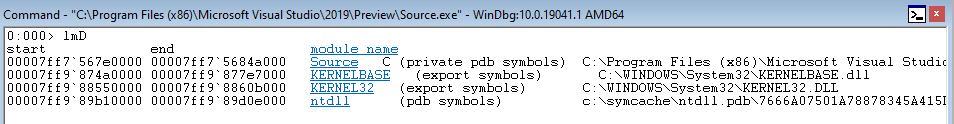

Adversaries want to return into a Windows API function like VirtualProtect() in order to dynamically change permissions of memory. What is interesting about CFG is that in addition to the program’s functions, all exported Windows functions that make up the “module” import list for a program can be called. For instance, the application we are looking at is called Source.exe Dumping the loaded modules for the application, we can see that KERNELBASE.dll, kernel32.dll, and ntdll.dll (which are the usual suspects) are loaded for this application.

Let’s see if/how this could be abused!

Let’s firstly update our program with a new function.

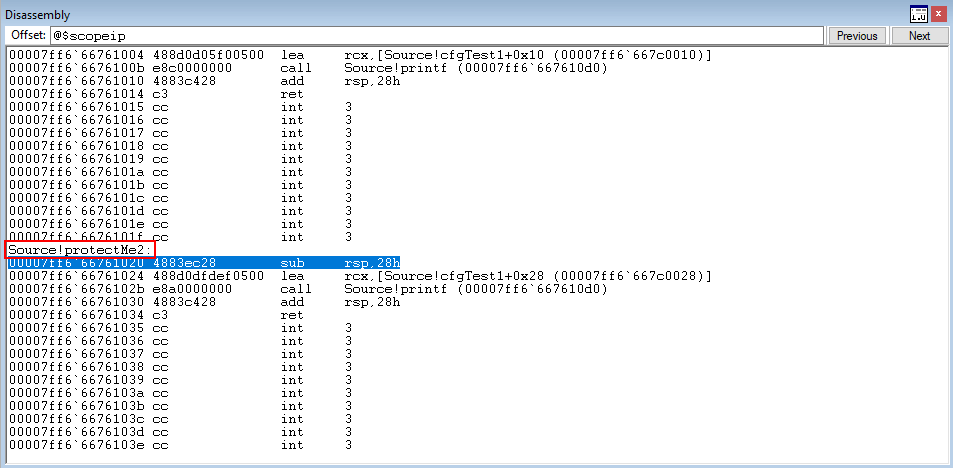

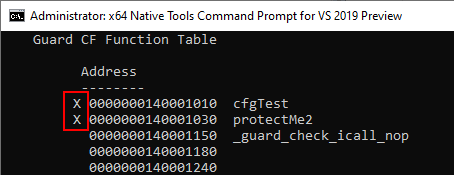

This program works exactly as the program before, except the function void protectMe2() is added in to add another user defined function to the CFG bitmap. Note that this function will never be executed, and that is poor from a programmer’s perspective. However, this function’s sole purpose is to just show another protected function. This can be verified again with dumpbin.

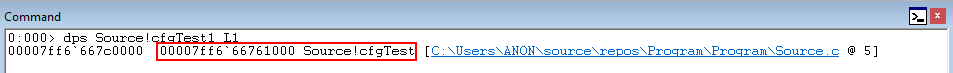

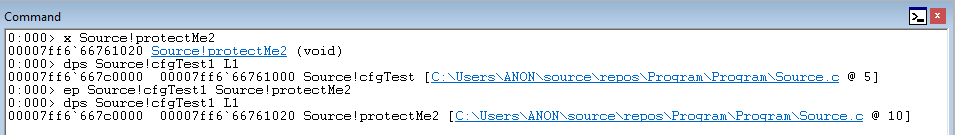

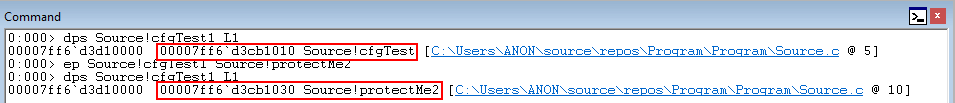

Here, we can see that Source!cfgTest1 still points to Source!cfgTest

Let’s recall what was said earlier about how CFG only validates if a function resides within the CFG bitmap or not. Let’s now perform a simulated arbitrary write condition in WinDbg to overwrite what Source!cfgTest points to, with Source!protectMe2.

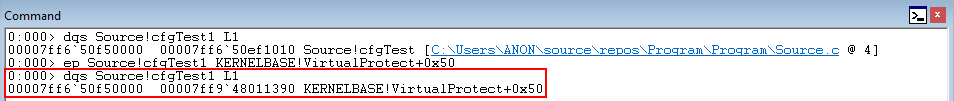

The above command uses x to show the address of the Source!protectMe2 function and then uses dps to show that Source!cfgTest1 still points to Source!cfgTest1. Then, using ep, we overwrite the function pointer. dps once again verifies that the function overwrite has occurred.

Let’s now step through the program to see what happens. Program execution firstly hits the CFG dispatch function.

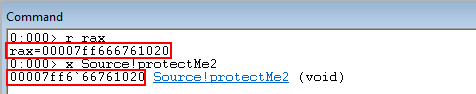

Looking at the RAX register, which is used to hold the address of the function CFG will check, we see it has been overwritten with Source!protectMe2 instead of Source!cfgTest.

Execution then hits ntdll!LdrpDispatchUserCallTarget. After walking the function, which validates if the in scope function resides within the CFG bitmap for the process, execution redirects to Source!protectMe2!

This is very interesting from an adversarial perspective, as we were successfully able to overwrite a function pointer and CFG didn’t terminate our process! The only caveat being that the function is a part of the current process’s CFG bitmap.

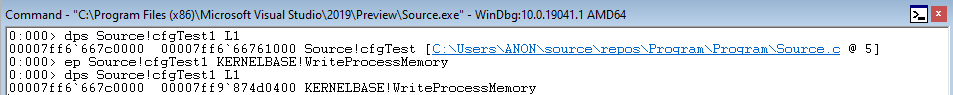

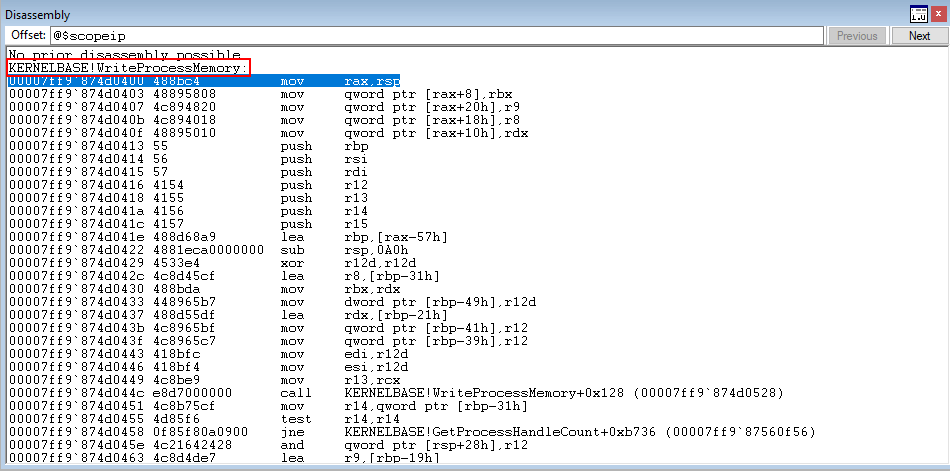

What is even more interesting, is that function pointers protected by CFG can be overwritten by any exported function at runtime! Let’s rework this example, but try to call a Windows API function like KERNELBASE!WriteProcessMemory.

First, we simulate the arbitrary write by overwriting Source!cfgTest1 with KERNELBASE!WriteProcessMemory.

Program execution passes through Source!__guard_dispatch_icall_fptr and ntdll!LdrpDispatchUserCallTarget and we can clearly see execution returns to KERNELBASE!WriteProcessMemory.

This shows that even with CFG enabled, it is still possible to call functions that have overwritten other functions. This is not good, as calls can still be made with malign intent. Additionally, calling functions of different types out of context may result in a type confusion or other programmatic behavioral problems.

Now that we have armed ourselves with an understanding of why CFG is an amazing start to solving the CFI problem, but yet still contains many shortcomings, let’s get into XFG and what makes it better and different.

XFG: The Next Era of CFI for Windows

Let’s start out by talking about what XFG is at a high level. After we go through some high level details about XFG, we will compile our program with XFG and walk through the dispatch function(s), as well as perform some simulated function pointer overwrites to see how XFG reacts and additionally see how XFG differs from CFG.

My last CrowdStrike blog post touches on XFG, but not in too much detail. XFG essentially is a more “hardened” version of CFG. How so? XFG, at compile time, produces a “type-based hash” of a function that is going to be called in a control flow transfer. This hash will be placed 8 bytes above the target function, and will be compared against a preserved version of that hash when an XFG dispatch function is executed. If the hashes match, control flow transfer is then passed to the in scope function that was checked. If the hashes differ, the program crashes.

Let’s take a look a bit more at this. Firstly, let’s compile our program with XFG!

Note that you will need Visual Studio 2019 Preview + at least Windows 10 21H1 in order to use XFG. Additionally, XFG is not found in the GUI compilation options.

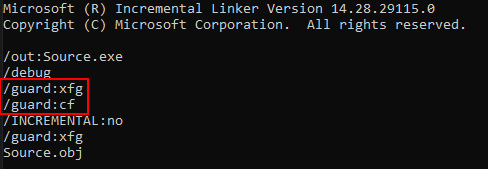

Using the /guard:xfg flag in compilation and linking, we can enable XFG for our application.

Notice that even though it was not selected, CFG is still enabled for our application.

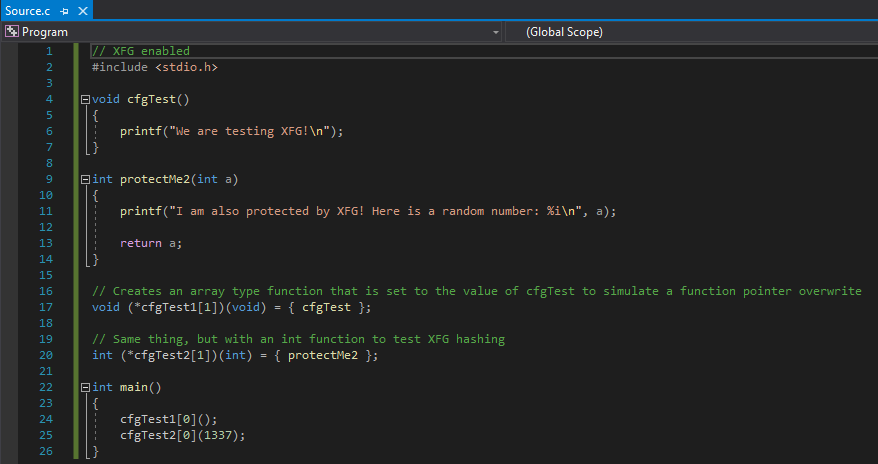

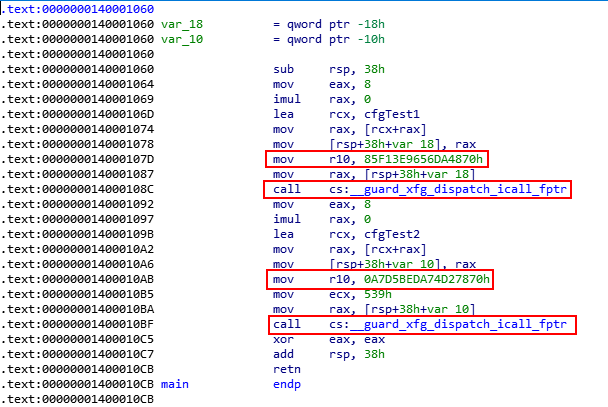

Let’s crack open IDA again to see how the main() function looks with the addition of XFG.

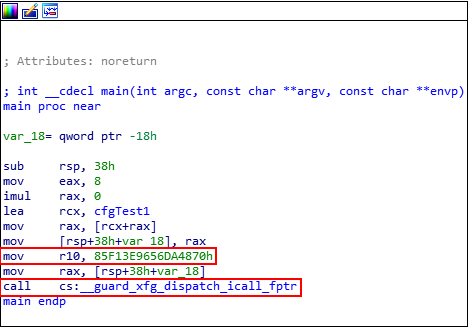

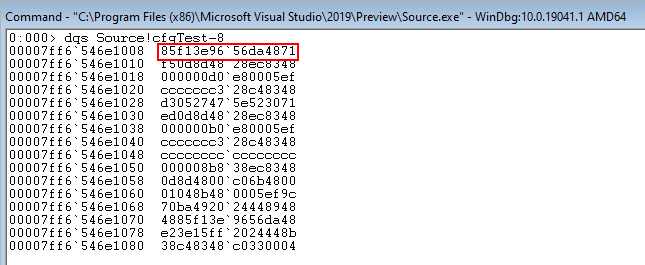

Very interesting! Firstly, we can see that R10 takes in the value of the XFG “type-based” hash. Then, a call is performed to the XFG dispatch call __guard_xfg_dispatch_icall_fptr. Note that the hash has been deemed “immutable” by Microsoft and cannot be modified by an attacker, due to its read only state.

In the image, below, the location of the XFG hash is at 00007ff7ded4110c

We can see that this address is executable (obviously) and readable - with the ability to write disabled.

Additionally, you can use the dumpbin tool to print out the functions protected by CFG/XFG. Functions protected by XFG are denoted with an X

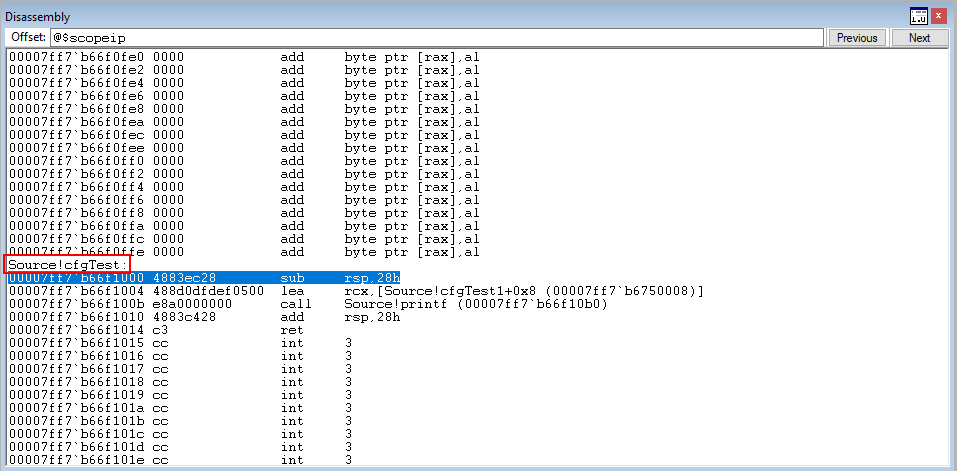

Before we move on, one interesting thing to note is that the XFG hash is already placed 8 bytes above an XFG protected function BEFORE any code execution actually occurs.

For instance, Source!cfgTest is an XFG protected function. 8 bytes above this function is the hash seen in the previous image, but with an additional bit set.

We will see why this additional bit has been set when we step through the functions that perform XFG checks.

Moving on, let’s step through this in WinDbg to see what we are working with here, and how execution flow will go.

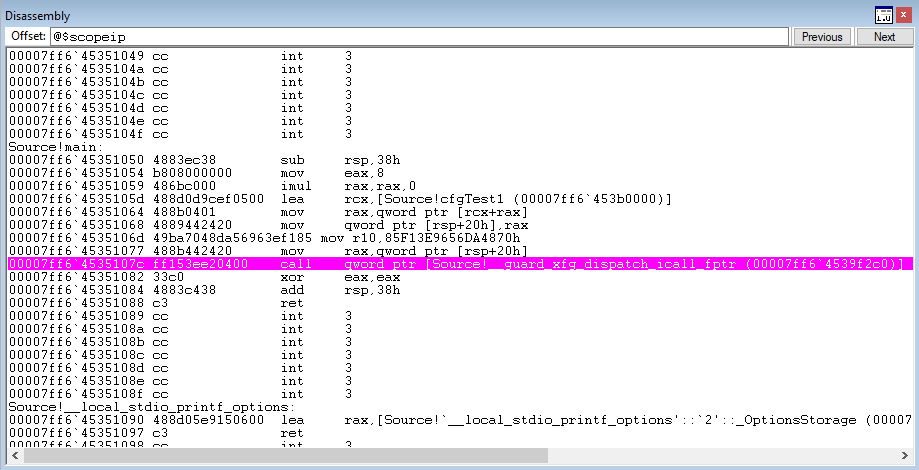

Firstly, execution lands on the XFG dispatch function.

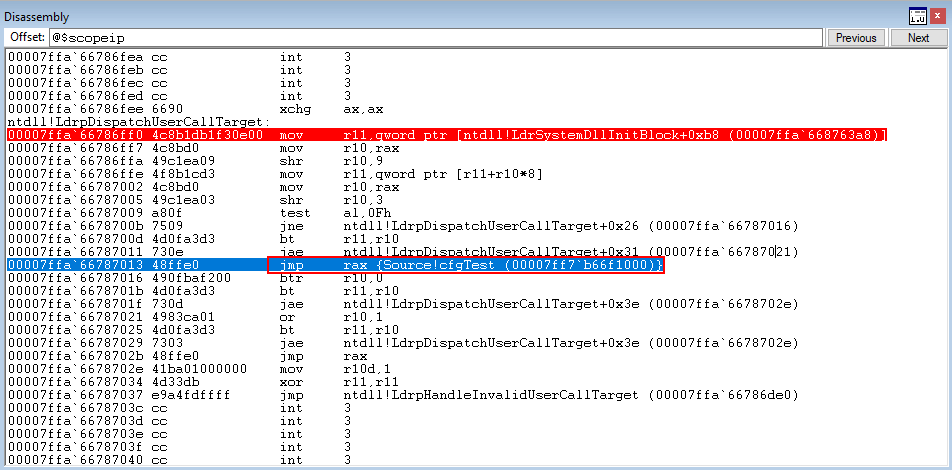

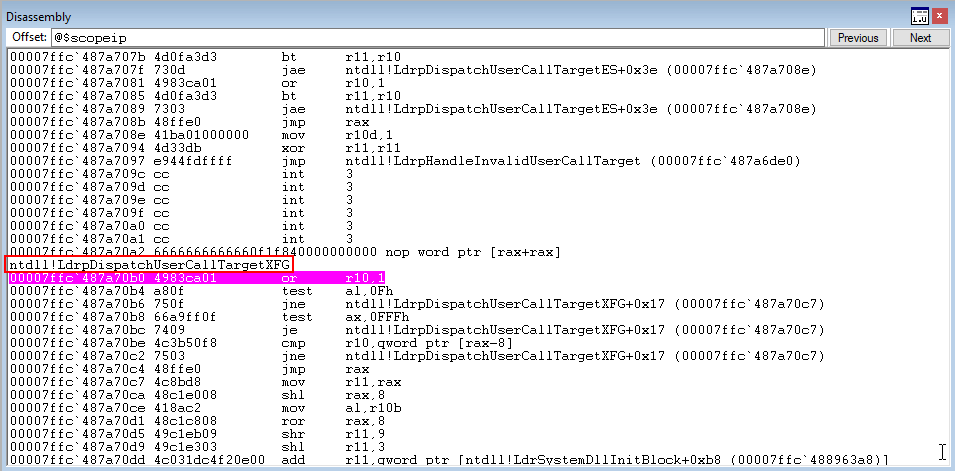

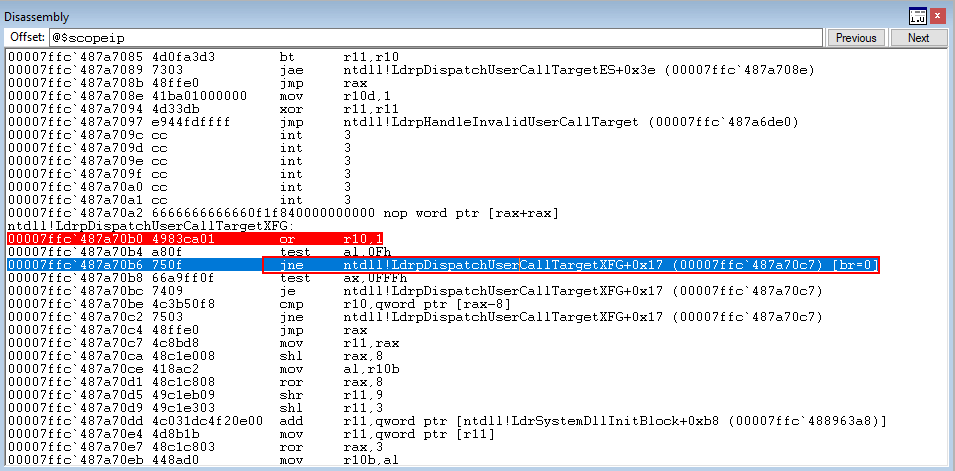

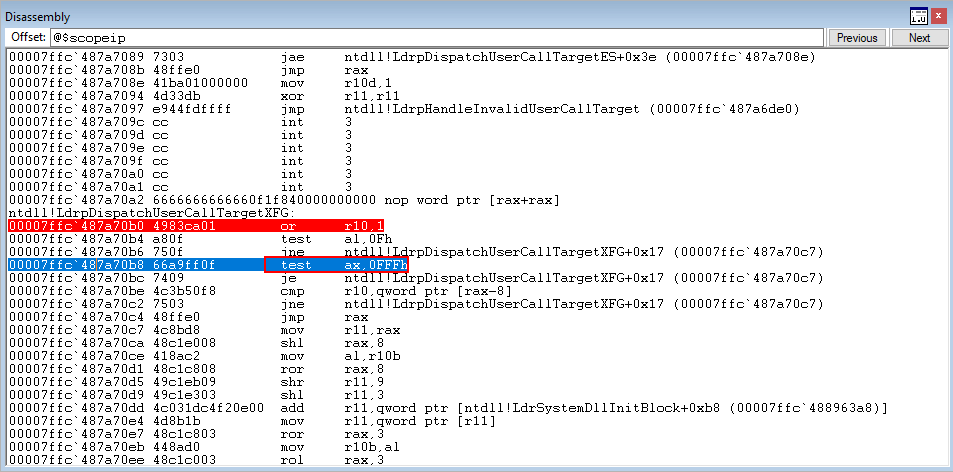

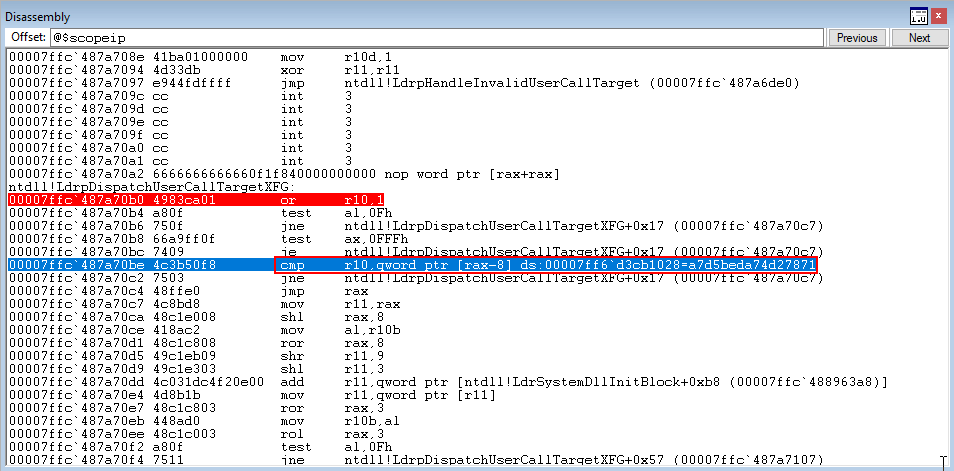

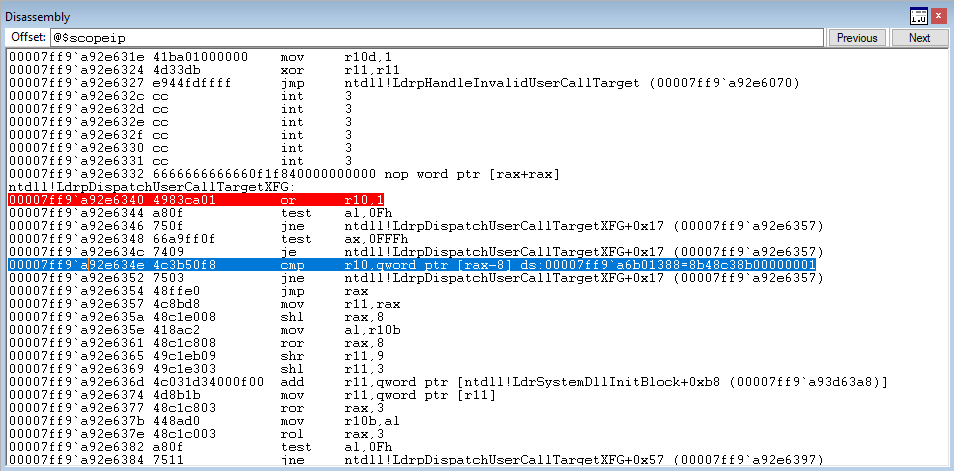

This time, when the __guard_xfg_dispatch_icall_fptr function is dereferenced, a jump to the function ntdll!LdrpDispatchUserCallTargetXFG is performed.

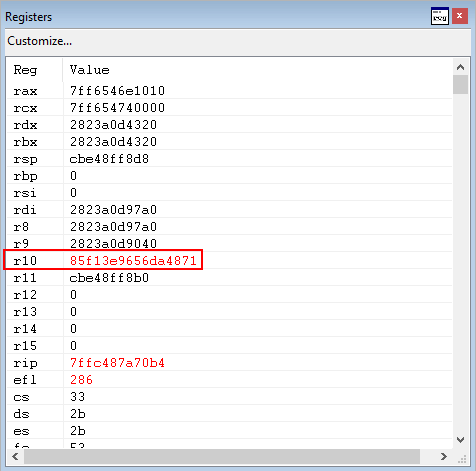

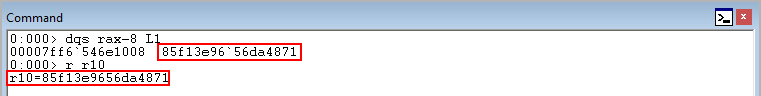

Firstly, a bitwise OR of the XFG hash and 1 occurs, with the result placed in R10. In our case, this sets a bit in the XFG function hash.

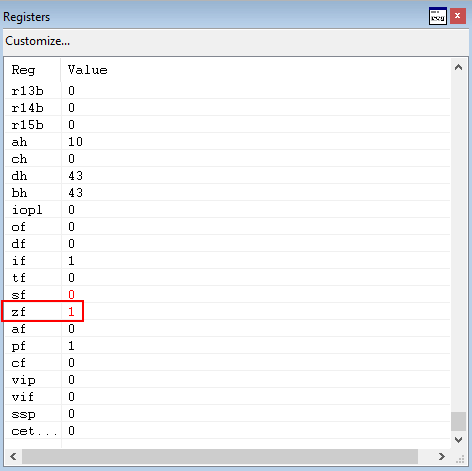

Next, a test al, 0xf operation occurs, which performs a bitwise AND between the lower 8 bits of AX (AL) and 0xf.

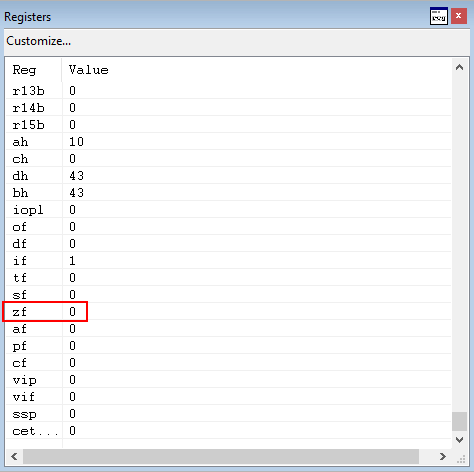

As we can see from the image above, this sets the zero flag in our case. Additionally, now we have reached a possible jump within ntdll!LdrpDispatchUserCallTargetXFG

Since the zero flag has been set, we will NOT take the jump and instead move on to the next instruction, test ax, 0xFFF.

Stepping through test ax, 0xFFF, which will perform a bitwise AND with the lower 16 bits of EAX and 0xFFF, plus set the zero flag accordingly, we see that we have cleared the zero flag in the image below. This means the jump will not occur, and we continue to move deeper into the ntdll!LdrpDispatchUserCallTargetXFG function.

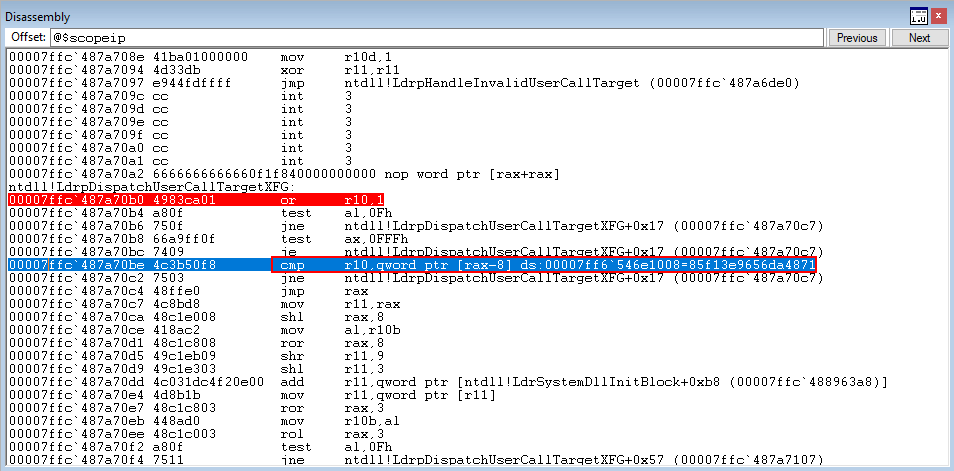

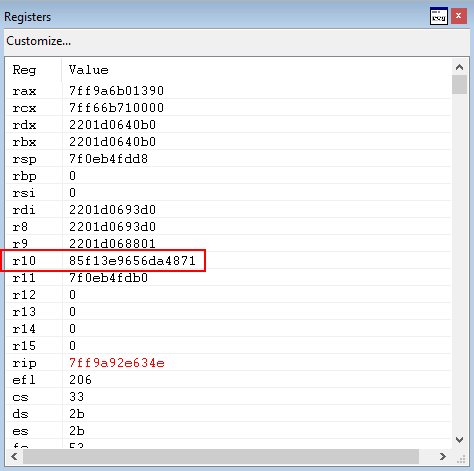

Finally, we land on the cmp instruction which compares the hash 8 bytes above RAX (our target function) with the hash preserved in R10.

The compare statement, because the values are equal, causes the zero flag to be set. This skips the next jump, and performs the final jump to our target function in RAX!

This is how a function protected by XFG is checked! Let’s now edit our code a bit and explore XFG a bit more.

Let’s Keep Going!

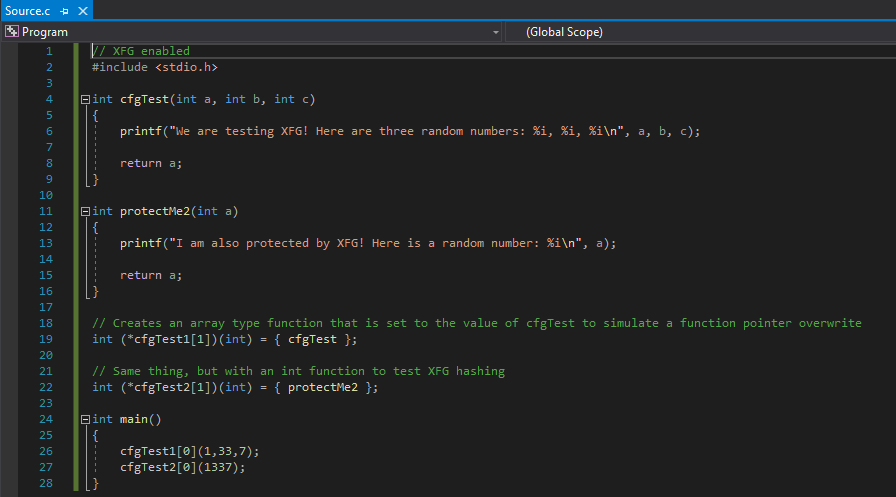

Recall that an XFG hash is made up of a function’s return type and any parameters. Let’s update our code to invoke another function of a different type.

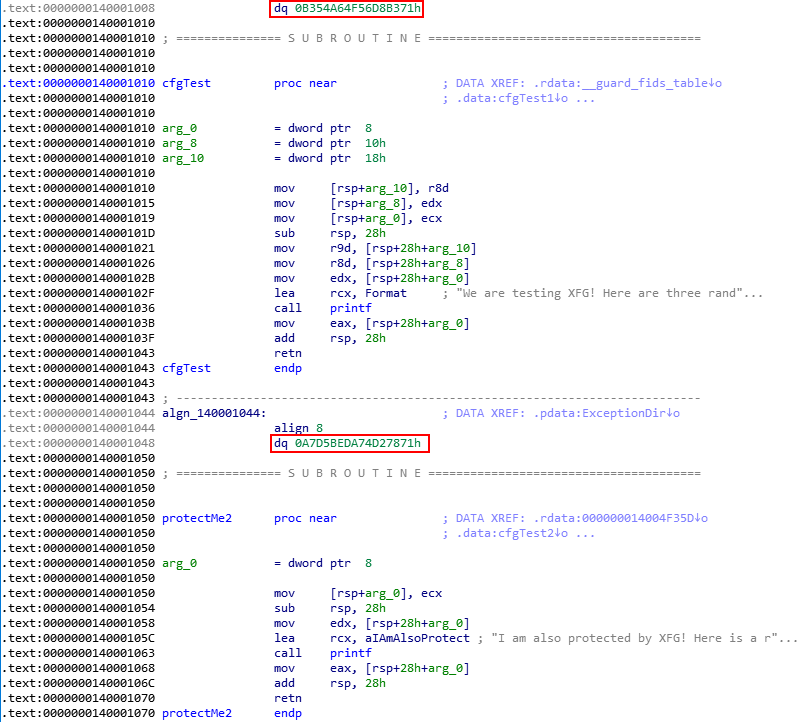

We have changed the protectMe2() function to a function that returns an integer and takes a parameter of the type integer. This is different than our void cfgTest() function. We also set a function pointer, int (*cfgTest2) equal to the int protectMe2() function in order to create a new XFG hash for a different function type (int in this case). Let’s recompile our program and disassemble it in IDA to see how the two functions may vary from an XFG perspective.

Very interesting! As we can see from the above image, there are two different hashes now. The hash for our original function has remained the same. However, the hash for the int protectMe2() function is very different, but the last 12 bits of each hash in hexadecimal is 870 in our case. This interesting and may be worth noting.

Additionally, static and dynamic analysis both show that even before any code has executed, the actual hash that is placed 8 bytes above each function. Additionally, the hashes already have an additional bit set, just as we saw last time.

Let’s take this opportunity to showcase why XFG is significantly stronger than CFG.

Let’s simulate an arbitrary write again by overwriting what Source!cfgTest1 points to with Source!protectMe2.

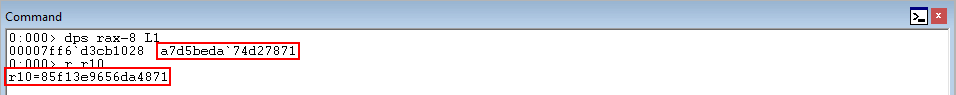

After simulating the arbitrary write, we pick up execution in ntdll!LdrpDispatchUserCallTargetXFG again. Stepping through a few instructions, we once again land on the cmp instruction which checks to see if the preserved XFG hash matches the current XFG hash.

As we can see below, the hashes do not match!

Since the hashes do not match, this will cause XFG to determine a function pointer has been overwritten with something it should not have been overwritten with - and causes a program crash. Even though the function pointer was overwritten by another function within the same bitmap - XFG still will crash the process.

Let’s examine another scenario, with two functions of the same return type - but not the same amount of parameters.

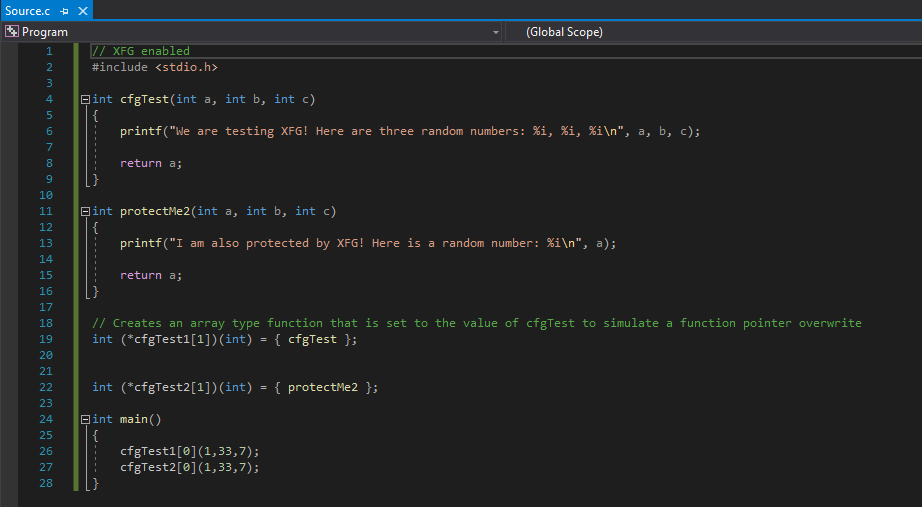

To achieve this, our code has been edited to the following.

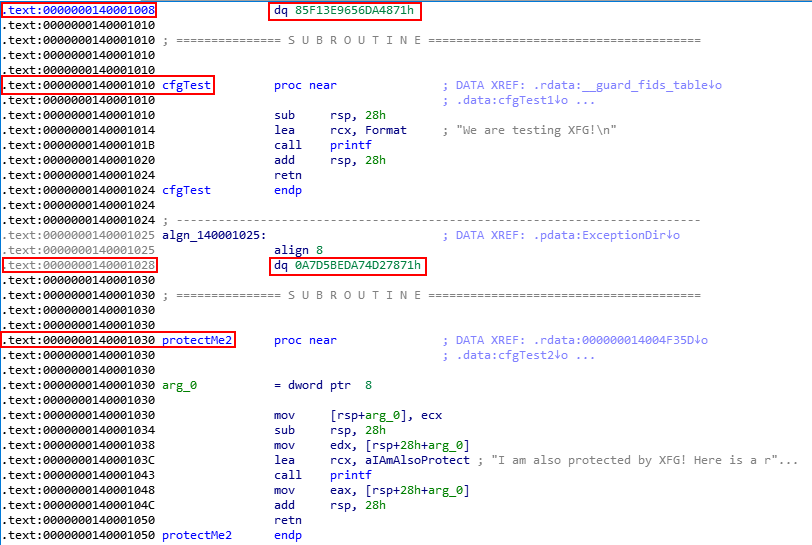

As we can see from the above image, we are using all integer functions now. However, the int cfgTest() function has two more parameters than the int protectMe2() function. Let’s compile and perform some static analysis in IDA.

The only difference between the two functions protected by XFG is the amount of parameters that int cfgTest() has, and yet the hashes are TOTALLY different. From a defensive perspective, it seems like even very similar functions are viewed as “very different”.

Additionally, we notice that the last 12 bits of the int cfgTest() hash have become 371 in hexadecimal instead of the previously mentioned 871 value. This means that XFG hashes seem to be unique until the last 8 bits. This is indicative of the hash only being unique up until about 56 bits.

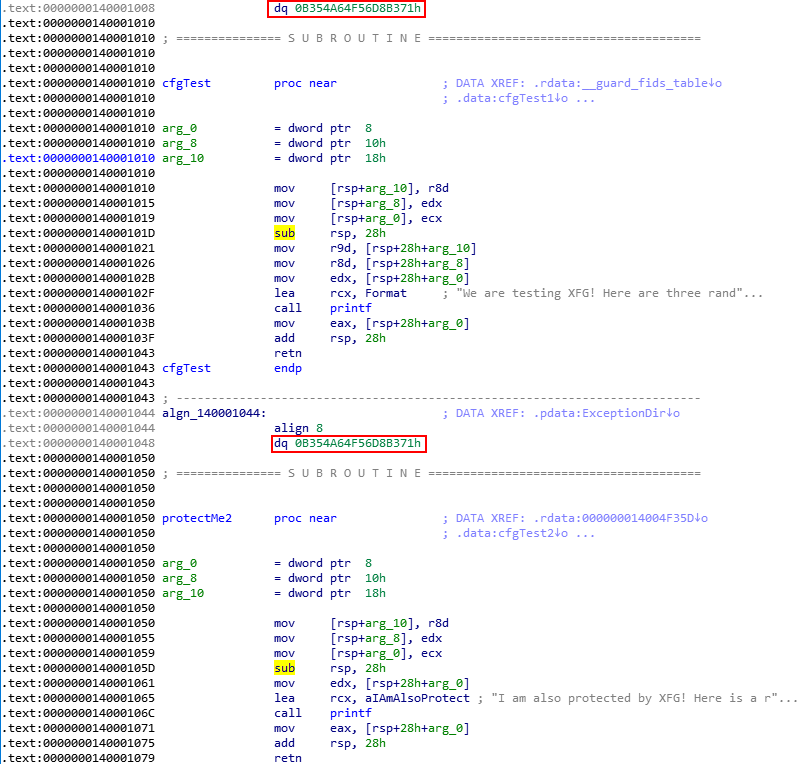

As a sanity check and for completeness sake, let’s see what happens when two identical functions are assigned an XFG hash.

OMG Samesies!

Here is an edited version of our code, with two identical functions.

Disassembling the functions in IDA, we can see that the hashes this time are identical.

Obviously, since the hashing process for an XFG hash takes a function prototype and hashes it, the two hashes are going to be the same. I would not call this a flaw at all, because it is obvious Microsoft knew to this going in. However, I feel this is a nice win for Microsoft in terms of their overall CFI strategy because as David pointed out, this was very little overhead to the already existing CFG infrastructure.

However, from an adversarial standpoint - it must be said. XFG functions can be overwritten, so long as the function is basically an identical prototype of the original function.

Potential Bypasses?

As mentioned above, utilizing functions of identical prototypes generates identical XFG hashes. Knowing this, it seems as though it could be possible to overwrite a function with an identical function of the same prototype. This is SIGNIFICANTLY stronger than CFG in terms of what functions can actually be called.

Let’s talk about one more (potential) additional potential bypass.

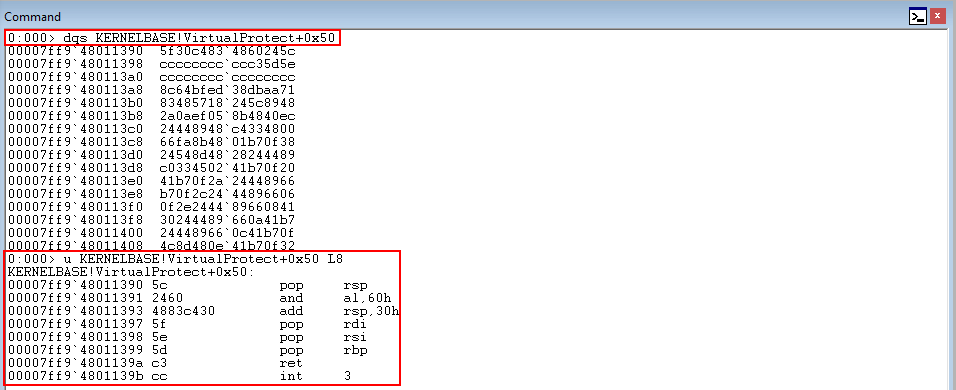

As we know, functions protected by XFG have an XFG hash placed above them (8 bytes above to be more specific). What would happen for instance, if we performed a function pointer overwrite and called into the middle of a function, like KERNELBASE!VirtualProtect.

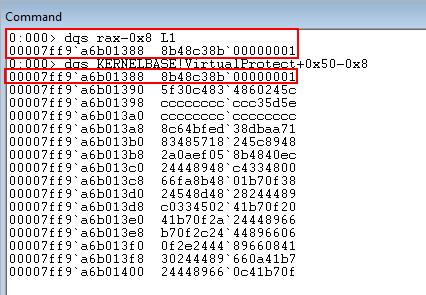

As we can see from the above image, calling into the middle of this function shows us that these hex numbers are being interpreted as opcodes, not memory addresses. This means that if XFG checks if a function pointer is overwritten by KERNELBASE!VirtualProtect, it would load the address of this function into RAX per the usual routine for XFG/CFG function checks. Then, this address is dereferenced at an offset of negative 8 to perform the XFG check. When this dereference happens, since this address contains opcodes, the opcodes that are present when calling into the middle of the function will be used in the XFG check.

Let’s perform a function pointer overwrite.

Note that the machine was restarted in between screenshots, causing addresses to change (but the symbols will remain the same).

Next, let’s step through the XFG dispatch functions and reach the compare statement.

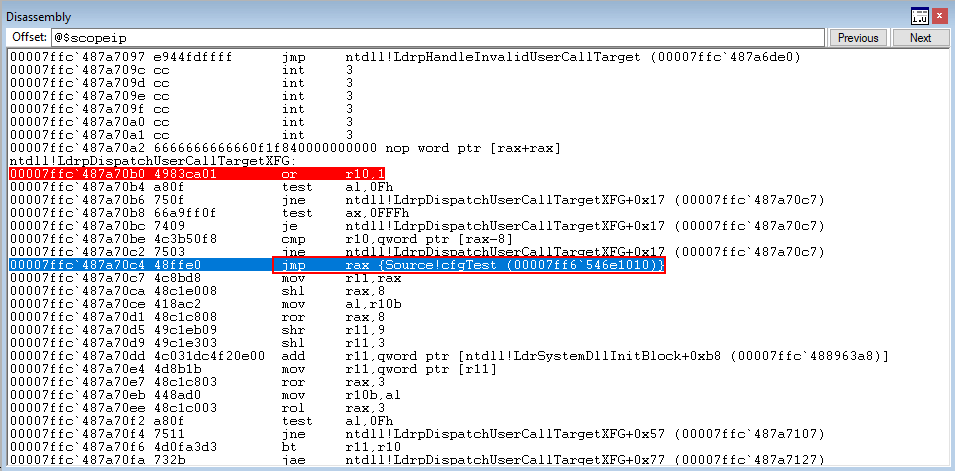

Hitting the compare statement, we can see that R10 contains the preserved XFG hash, while RAX just contains the address of KERNELBASE!VirtualProtect + 0x50.

Taking a look at RAX - 8, where the XFG check occurs, we can see that the opcodes that reside within KERNELBASE!VirutalProtect are being treated as the “compared hash”.

Although this compare will fail, this brings up an interesting point.

Since calling into a middle of a function results in the function’s data being treated as opcodes and not memory addresses (usually), it may be possible for an adversary to utilize an arbitrary read/write primitive to do the following.

- Locate the XFG hash for a function you want to overwrite

- Perform a loop to dereference the process space’s memory and look for patterns that are identical to the XFG hash (remember, we still have to abide by CFG’s rules and choosing a function exported by the application or a function that is additionally located in the same bitmap)

- Overwrite the function pointer with any viable candidates

Although you most likely are going to be very hard pressed to find anything identical to the hash in terms of opcodes in the middle of a function AND additionally make whatever you find useful from an attacker’s perspective, this is still possible it seems.

Final Thoughts

I think personally that XFG is an awesome mitigation and I am excited to see how people get creative with the solution. However, until CET comes into play, overwriting return addresses on the stack seems like it will still be fair game. I think the combination of XFG and CET is going to be very interesting for exploitation in the future. I think XFG is a great and pretty creative mitigation. However, it has yet to be seen yet how it performs against Indirect Branch Tracking (IBT), which is CET’s forward-edge protection. All together, I think Microsoft has done a great thing with XFG by implementing it and not letting all of the work done with CFG go to waste.

As always! Peace, love, and positivity :-)